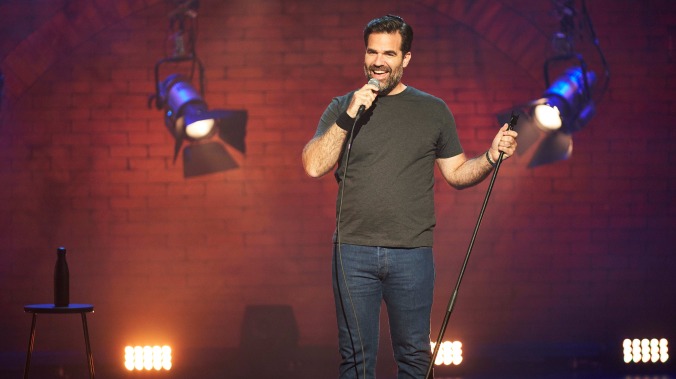

Rob Delaney’s engaging assholery shines in his new special Jackie

Rob Delaney beams. In his new standup special, Jackie, the strapping American ex-pat regales his appreciative London audience with jokes delivered via toothy smile and forthright body language, landing anecdotes about everything from fatherhood, to politics, to weight gain, to the harrowing loss of his beloved pet lizard (named Jackie) with the outwardly genial gustiness of an elbow to the ribs. Such punchiness of delivery has always been Delaney’s métier, the carryover from his influential Twitter account to his onstage persona maintaining the comic’s brashness and aggressiveness of tone, even as his stand-up style veers into his more expansive storytelling style.

For Delaney, who’s lived in the U.K. since his stellar comedy series Catastrophe was picked up by Channel 4 in 2014, playing to his adoptive countrymen is a decided asset. A comedian has to portray himself as somehow smarter than his audience—or at least the subjects of his jokes. But Delaney’s position as outsized Yank in London adds a certain conspiratorial edge to jokes about, for example, the differences between his two countries’ relative approaches to health care. “If the N.H.S. [British National Health Service] had a dick, l I would suck that dick,” booms Delaney when wrapping up the comparison, and the wash of greeting laughter encompasses the crowd’s multilayered appreciation. Delaney’s telling a dick joke (not the first or last of the night), slamming the “medical terror” of getting sick in the United States, and yet noting how the British system’s stalwart practicality tempers any undue enthusiasm with the crisply noncommittal attitude, “No promises, but we’ll take a look.” For a comedian who traffics in superior snark, getting to play both blundering outsider and knowing insider is a potent position to be in.

Still, for a comic who presents so boldly, tone remains something of a problem for Delaney, whose barely existent transitions and lack of polished finishes to some bits keeps Jackie from cohering into something smoother, and bigger. Delaney’s got a prankish streak to him, starting off one bit about British reserve with the breezy introduction, “I think it’s good that Nazi bombs fell on your grandparents, and I’ll tell you why…” His British audience loves his cheek when Delaney kicks off another run on his new home by announcing, “I love the monarchy, because fuck them, they should not exist,” following up with a parallel mockery of Americans’ pumped-up fantasies of rising from poverty to the halls of power. “Born in a ditch, die in a ditch,” Delaney sums up the ever-present weight of royalty and tradition in good old England.

Delaney’s is a paradoxically cozy misanthropy, gleeful in tearing down outright assholes while lumping himself into his overriding assumption of failure and embarrassment. A section detailing his youthful alcoholism and the horrific car accident that saw him essentially helpless—first in a jail cell and then a mental hospital—emerges with no-nonsense forthrightness. Meanwhile, his family material positions Delaney as the bumbling buffoon of a thousand dad stories, all the while holding himself up as the one true voice of thwarted reason. There’s a lot lurking in his self-portrait as loving but smart-ass dad and husband, as anyone who’s seen Catastrophe’s complex portrait of marital and parental pain and absurdity already knows. (And those familiar with Delaney’s infinitely more wrenching recent family history know even more.) A story about children’s garden chaos involving his three young sons allows Delaney to play around with the tropes of monstrous kids versus tough love dad with amiable, knockabout matter-of-factness. Pinning his misbehaving eldest son against the wall with the forceful spray of a garden hose winds up eliciting the sort of chillingly pure promise of vengeance that only one’s own child can conjure.

It’s good stuff, although, like too many of Delaney’s stories, it could use some shaping. But, also like much of Delaney’s material, it skirts performative glibness rather than cutting very deep. And that’s a choice that can work, but only if you craft your material with more care. No performer has to justify the extent to which they mine their personal life for material. There’s a dignity in the choice to eschew exhibiting your personal pain for the entertainment of others, just as there’s artistry in turning the unthinkable into art, especially comedy. In that same garden story, Delaney slips in just one telling detail, excusing his self-admitted assholery in turning a hose on one son by saying plainly, “If you punch my beautiful six-year-old in the face, I’m gonna fuckin’ hose you.” There’s a running, almost grudging theme of aching adoration running through Delaney’s material here when it comes to his kids—a late story about his two sons gigglingly peppering him with questions about homosexuality fairly glows with amused affection. When Patton Oswalt transformed his wife’s shocking death into the devastatingly funny Annihilation, or Hannah Gadsby made Nanette into a 60-minute gut-punch, the workmanship in shaping life’s own hateful capriciousness was breathtaking. Conversely, when fellow lumbering dad comic Jim Gaffigan trod similar tender ground, he defused it by applying his same style to the horrific and terrifying, essentially unchanged. Delaney strides over it as if the past didn’t exist, except in the most oblique references to the preciousness of the very people he’s using for material.

As a stand-up strategy, it’s affecting in its own way, even as Delaney’s late story about the loss (and eventual, miraculous salvation) of the special’s titular bearded dragon sees him expressing more emotion than anywhere else in the hour. Starting out as a standard bit about kids not following through on caring for a new (as it turned out, impossibly demanding) pet, the anecdote flows through the comic’s irrational but genuine love for the little monster, whose escape (caused by his kids’ carelessness) sees him unleashing a firehose of abuse on those around him who haven’t properly valued what they’ve just lost. As he explains, in graphic detail, just how the temperature-sensitive creature is likely suffering thanks to their negligence, Delaney’s joke is on himself for being the sort of asshole who’d do such a thing, all while relishing futile pettiness of making his family members cry, concluding by telling them Jackie “went to hell because of a series of choices that you made.” Jackie’s happy ending aside (once more playing ably with words, Delaney describes himself happily “cunniling-ing” mashed-up berries into the rescued Jackie’s mouth), the story edges into the genuine darkness behind Delaney’s bluff persona, before he sweeps it aside.