Rob Reiner achieves a very minor comeback with Being Charlie

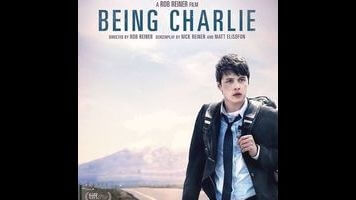

Being Charlie’s teenaged title character hails from a world of extreme privilege. His father, David Wells (Cary Elwes), is a former A-list movie star, famous for his pirate adventures, who’s now running for governor of California—sort of a bizarre cross between Johnny Depp and Arnold Schwarzenegger (though the pirate bit is likely a nod to Elwes’ role in The Princess Bride). Charlie, too, has showbiz aspirations—he’s done some open-mic performances as a stand-up comic—but there’s a slight hitch: He’s an unrepentant junkie who keeps fleeing the expensive rehab centers where his dad parks him. The movie was co-written (with Matt Elisofon) by one Nick Reiner, who’s all of 22 years old, and it’s loosely autobiographical, based on his own experiences in rehab… and on his battles with his own famous father, who directed it. Perhaps because of that personal connection, Being Charlie is Rob Reiner’s best film in at least two decades—admittedly a low bar to clear, given the competition (which includes such forgotten piffle as Alex & Emma and Rumor Has It…), but even a modest Meathead comeback is more than welcome.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.