The films of Rob Zombie, shock rocker turned grindhouse revivalist, usually have more attitude than they do raw terror. Yes, the guy who made The Devil’s Rejects can provoke the hell out of a gag reflex—his down-and-dirty throwbacks lay on the carnage with a trowel—and he’s certainly learned how to approximate the look and feel, the outsider-art griminess, of the cult classics he reveres. But for Zombie, who cut his teeth behind the camera of his own music videos, each gig is also an extension of his graveyard-boogie brand. He doesn’t direct movies so much as throw elaborate Halloween (or Halloween) parties: His friends and family are usually there in costume, the theme is almost always “hillbilly horror,” and who needs a DJ when the local classic-rock station is pumping out the super sounds of the 1970s?

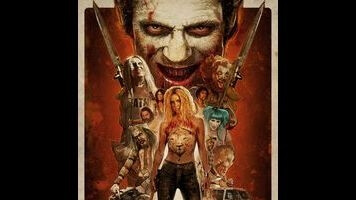

Zombie’s new movie, 31, is all attitude. It’s also the worst thing he’s ever made—interminable, incoherent, and devoid of suspense. The film is set on Halloween night 1976, when foulmouthed carnies (most played by character-actor veterans of the genre) are forced into an all-night death match, staged for the amusement of sadistic aristocrats in powdered wigs. For Zombie, that scenario is little more than an opportunity to play his greatest hits, running through them like lines on an anniversary-tour set list. That means freeze frames, copious amounts of Hee Haw comedy, and a starring role for the director’s wife and muse, Sheri Moon Zombie. It also means lots and lots of creepy clowns, because in a Zombie project, horror doesn’t run skin deep—it stops at the thick layer of white makeup slathered over the actors’ faces.

The filmmaker clearly nurses some affection for the latest flock of lambs he leads to the slaughter, introduced cruising down a sun-baked highway in a van like the doomed teens of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. But he never plays their life-and-death ordeal for much fatalistic anxiety. 31 is set almost entirely within a smoky, leaky, dimly lit factory, like something out of a bad hair-metal video, and it has the structure of an especially half-assed video game, as the survivors creep from one boss battle to the next, confronted by assassins of escalating formidability: a little person done up like Hitler, slinging insults in unsubtitled Spanish; two clowns with chainsaws, cackling about “fucking all your holes”; a flirtatious Harley Quinn clone with a giant European partner. Every step of the way, they’re taunted via PA system by their moneyed game master, sadly played (or more often just voiced) by Malcolm McDowell.

Zombie’s self-consciously retro exploitation movies are often too homage-happy to score deep scares; they put hardcore horror in quotation marks. At his best, the director knows how to orchestrate a striking, memorable set piece, like the murder by headlights in the second of his barbarically extreme Michael Myers revivals. But in 31, Zombie films the bloodshed in queasy close-up, frequently rendering its close-quarters combat nearly incomprehensible. The writing is worse: a blue streak of “edgy” vulgarities, suggesting the sensibility—and sense of humor—of a 13-year-old trying out nasty words for the first time. The film’s juvenile, posturing nihilism finds flesh-and-blood embodiment in the character of Doom-Head (Richard Brake), a hit man who screws to Nosferatu, applies his makeup to Beethoven, and quotes Karl Marx before a kill. Introduced in the black-and-white prologue, delivering a monologue straight into the camera, Brake almost sells his sub-Tarantino psycho tough-guy dialogue. Almost.

The Tarantino comparison is useful. Zombie, like the king of the video-store geeks, has a seemingly bottomless appetite for pop culture; and he packs his movies with references to the cinema, music, and back-country trash Americana he loves. The difference is that Tarantino often subverts his genres of choice, smartly denying his audience the expected conventions and payoffs. Zombie, when not catering to his own tastes, would rather pander to an indiscriminate midnight-movie crowd—the kind that might respond on cue to every “badass” prompt, like a slow-motion finale set to Aerosmith, in a blatant attempt to recapture the “Freebird” sublimity of those kamikaze final minutes in The Devil’s Rejects. A messy mishmash of shit he’s done better before, 31 may well satisfy the witching-hour masses. But will it get under anyone’s skin? Dream on.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.