Robert Altman affectionately skewered Hollywood with The Player

Robert Altman’s adaptation of Michael Tolkin’s The Player—a novel that eviscerates ’80s Hollywood—begins with a lengthy joke that only cinema could make. As a studio security chief (Fred Ward) bitterly complains about the era’s ADD aesthetic (“All this cut, cut, cut,” he grumbles, blissfully unaware that Michael Bay lurks in his future) and raves about the opening of Touch Of Evil, Altman and cinematographer Jean Lépine execute a ludicrously complex seven-minute shot that wanders all over the lot, even peeking through several windows at pitch meetings in progress. Many of The Player’s major players are introduced over the course of this sequence, and there are some magnificent jokes, including Buck Henry’s pitch for The Graduate: Part 2 (or maybe The Post-Graduate) and Alan Rudolph describing a project as “politely political, but with a heart, you know, in the right place.” (That Rudolph hasn’t been in a film since 2002 makes the latter sting a bit more today.) Still, the main gag is the shot itself, which seeks to impress even as it pokes fun at its own ambition.

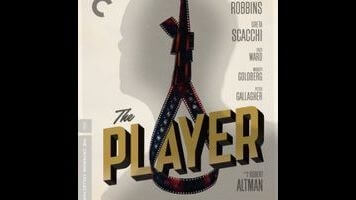

If Altman loves movies too much to replicate Tolkin’s acrid tone, however, that doesn’t stop his version of The Player (which joins the Criterion Collection on Tuesday) from being a lot of fun. The basic plot remains the same: Studio boss Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins, then at the height of his fame), who’s already worried that he’s about to lose his job to rival Larry Levy (Peter Gallagher), has been receiving threatening postcards from an anonymous source who claims to be a mistreated, vengeful screenwriter. Griffin pegs David Kahane (Vincent D’Onofrio) as the likeliest suspect and tracks him down at an L.A. rep house, offering to set up a deal for him if he’ll stop with the postcards. This would-be friendly meeting concludes with Griffin drowning Kahane in a puddle of water, sparking a police investigation that only intensifies when the main cop (Whoopi Goldberg) discovers that Griffin has become romantically involved with Kahane’s ex-girlfriend, June (Greta Scacchi). All the while, Griffin tries to get rid of Levy, primarily by directing him toward a guaranteed box-office disaster, Habeas Corpus, about a falsely accused death-row inmate fated for the gas chamber.

That might sound like a lot of narrative, but none of it ultimately matters much, except insofar as it inspires some first-rate comedy. (The conclusion of the whole Habeas Corpus subplot, featuring cameos from two of the biggest movie stars in the world at the time—they’re still pretty huge now, too—is Hollywood self-mockery at its finest.) Altman uses his usual chaotic, overlapping dialogue and abrupt, attention-shifting zooms in a context full of familiar faces, having convinced dozens of celebrities to pop in as themselves; the result has a fun-house-mirror quality that he makes explicit in a wildly stylized sex scene midway through the film. The fact that so many stars signed on is an indication of how affectionate this ostensible poison-pen letter is, but some of Tolkin’s distaste does get through. The film’s most cutting scene has Levy demonstrating how little the industry needs screenwriters by having fellow suits read him random newspaper headlines, from which he instantly concocts credible log lines. Nearly a quarter-century later, what’s bitterly funny isn’t so much the contempt Levy displays toward “creatives,” rather the notion that Hollywood movies would be inspired by current events or anything that one might find in a newspaper (or that newspapers exist). Were Altman still with us, what would he think of the Marvel Cinematic Universe? Any version of The Player that his ghost might make today would probably be a lot less jocular.