“Revisionist Western” has become a redundant distinction. After all, we live in an age when the very few Westerns that still get made are almost all postmodern in outlook—challenging this once-dominant genre’s most romantic clichés, depicting frontier life with unsparing historical accuracy, pushing back against the rosy racism of Golden Age cowboys-and-Indians stories. Set in 1870, Damsel, from sibling filmmakers David and Nathan Zellner, isn’t revisionist in the same way as something like Unforgiven—it’s poky and quirky, not grim and elegiac, with faintly anachronistic dialogue and a dryly comic sensibility. What the film most revises, really, is its own apparent trajectory, eventually landing on a subversive and unexpected plot development—one, it must be admitted, that starts to look like the only truly remarkable thing about the movie.

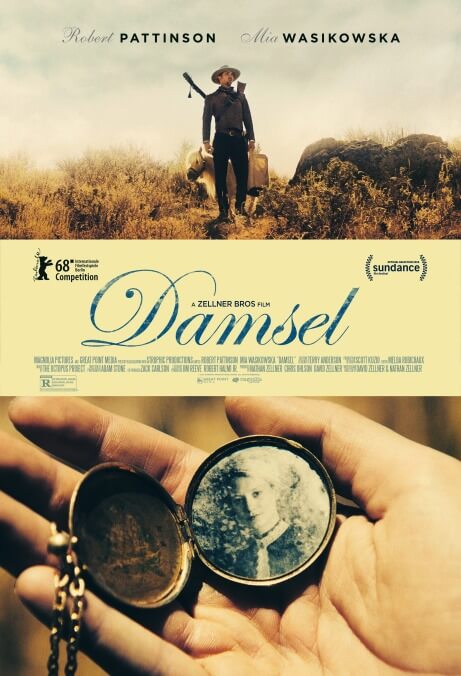

With Damsel, the Zellners have made a kind of artisanal thrift-shop approximation of a Western. That’s clear from the moment that Robert Pattinson, beaming brighter than usual thanks to a gold tooth where one incisor should be, saunters into the one-drink saloon of a one-horse town—a location so ingrained in the genealogy of the genre that it’s all but impossible not to put quotation marks around it. Fresh off his revelatory, career-high performance in Good Time, Pattinson has cranked up the eccentricity to play Samuel Alabaster, a lovesick businessman on a mission. Samuel has come to find Parson Henry (David Zellner himself, a bit out of his league), an alcoholic preacher he’s hired to officiate his wedding—a task, the holy man soon discovers, that will involve accompanying the stranger on a multi-day journey west through the wilderness. Their third companion on this pilgrimage: a miniature horse named Butterscotch, the dandy’s wedding present to his bride to be, Penelope.

Things are not exactly as they seem. Parson, a charlatan as well as a drunk, is further surprised to learn that a little gunslinging may be required of him—they aren’t just finding Samuel’s sweetheart, but also rescuing her! This is where Damsel starts to toy with the expectations set by both its ostensible protagonist and our own familiarity with stories about men in spurs galloping to the aid of women in peril. Penelope, to whom the perspective eventually shifts, is played by Pattinson’s Maps To The Stars co-star Mia Wasikowska, and she’s no withering violet. Quite to the contrary, and contrary to the title, she turns out to be a force of enraged self-sufficiency in the barren, untamed Wild West. The role is no stretch for Wasikowska, who has played more than her share of proto-feminist heroines born too soon, from a swashbuckling Alice in Wonderland to a headstrong Jane Eyre. Here, though, she seems almost pointedly out of time: a modern soul stranded in a cruel, stupid, backwards world.

To reveal much more about where Damsel goes would spoil the fun. Suffice to say, the film has one damning point to make, and it makes it over and over again, through a great twist that leads to a pretty good running joke. But once you’ve gotten the punchline, and what it’s trying to convey about masculinity and heroism, all that’s left to admire is the Zellner brothers’ particular brand of deadpan minimalism, splashed this time against sprawling, sometimes almost otherworldly vistas. Like their last film, Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter, which built an offbeat fish-out-of-water story on an urban legend of Fargo fandom, Damsel is episodic and plainly indebted to the daft Hollywood pastiches of the Coen brothers. The opening scene, in fact, could come right out of No Country For Old Men, with Robert Forster popping in for a brief cameo as a country preacher who’s lost his will to live. “Things are going to be shitty and new in fascinating ways,” he remarks, hitting a note of resignation somewhere between comedy and tragedy, the vast chasm where most of the film resides.

Damsel keeps throwing new oddballs at the screen, from a brutish Daniel Boone type (the other Zellner brother, Nathan) to a wandering Native American (Joseph Billingiere) who basically paraphrases Gary Farmer’s famous “Stupid fucking white man” speech in Dead Man—another plain influence here—through withering looks and asides. But the film pivots around the romance, as it were, between Samuel and Penelope. In so much as they still exist, revisionist Westerns are about reevaluation. Damsel is no different; by flipping the tables on its own narrative, the film casts a whole lineage of Old West mythmaking under suspicion. It’s a neat, provocative trick. It’s also about all this on-point, one-note oater has going for it, provided the sight of R-Patz leading a pony through the desert isn’t quite pleasure enough.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.