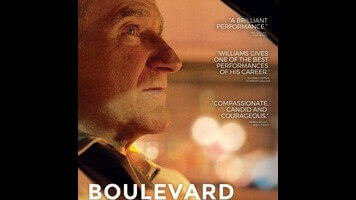

Robin Williams deserved a better swan song than Boulevard

Robin Williams was a great comic actor, and at times he could be a very effective dramatic actor as well. Without a strong director to rein him in, however—a Peter Weir or a Gus Van Sant or a Christopher Nolan—he had a tendency to think he was projecting “deep” when he was actually turning in something uncomfortably close to “moist.” Boulevard, the final theatrical release in which Williams plays the lead role (he has one voice-only performance as a dog that’s still pending), was directed by Dito Montiel (A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints, The Son Of No One), who clearly lacked either the will or the authority to keep his star from laying on the morose regret with a trowel. There’s no joy in reporting that this beloved actor’s last handful of movies were stinkers (see also A Merry Friggin’ Christmas and The Angriest Man In Brooklyn), but honoring the great work he did requires acknowledging the lousy work as well.

It doesn’t help that Boulevard is a movie that feels at least a decade past its sell-by date, if not two. Williams plays Nolan Mack, a rather meek fellow who’s spent his entire adult life married to the same woman, Joy (Kathy Baker), and working at the same dead-end job, pushing papers around at a small Nashville bank. Nolan and Joy have an affectionate rapport, but they sleep in separate bedrooms, and it comes as no big surprise when Nolan, driving home one night after visiting his hospitalized father, suddenly stops his car alongside some young men who are pretty clearly for sale. As it turns out, though, Nolan doesn’t want sex, to the befuddlement of Leo (Roberto Aguire), the guy he picks up. He’s content simply to look at Leo naked, hold him occasionally, and help him out financially. Joy, meanwhile, seems to be well aware that her husband is gay—she repeatedly catches him in lies, never confronting him—but that doesn’t necessarily mean that she’s ready for him to end the marriage and pursue real happiness.

Arriving several years after Beginners, for which Christopher Plummer won an Oscar as an octogenarian who joyously embraces his homosexuality late in life, the soggily repressed Boulevard plays like the two steps back to that film’s one step forward. Screenwriter Douglas Soesbe’s decision to make Nolan more or less asexual can be justified psychologically—after a lifetime spent in the closet, one might well be terrified of acting on genuine desire—but the lack of even some tentative exploration feels like an act of cowardice by the filmmakers rather than by the character. Williams tries hard to convey Nolan’s sense of liberation (with Leo) and guilt (with Joy), but that’s the problem, as it often was: He tries way too hard, telegraphing the character’s emotions so furiously that the performance becomes overbearing. (That the super-relaxed Bob Odenkirk plays Nolan’s best friend compounds the problem.) It’s left to Baker, who rarely gets a part this juicy nowadays, to provide some much-needed subtlety; the scene in which Joy finally speaks her mind about why she married Nolan provides Boulevard with its sole incisive moment. Had the film been more about that relationship, instead of focusing almost exclusively on its protagonist’s soft-spoken, wet-eyed ineffectuality, perhaps it could have served as a better swan song.