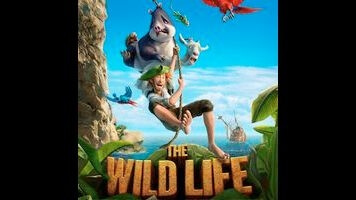

Robinson Crusoe gets a cruddy animated makeover with The Wild Life

There have been several attempts to revisit Robinson Crusoe from the point of view of loyal sidekick Friday, but up until now, no one has tried to tell the story from the perspective of Crusoe’s parrot, dog, and goat. In comes Belgian animation studio NWave Pictures (previously behind Fly Me To The Moon, which depicted the Apollo 11 mission from the perspective of… some houseflies) with The Wild Life, the sort of uninspired international pre-sales item that usually goes straight from a basement booth at the Cannes film market to a Netflix parent’s peripheral vision. The sole interesting thing about NWave’s animation is its use of the camera, which plays to 3-D’s pop-out factor; otherwise, its movies (like Thunder And The House Of Magic and A Turtle’s Tale: Sammy’s Adventures, both directed or co-directed by founder Ben Stassen) are pap, cranked out on an artless formula. Combine one small animal protagonist eager to discover the larger world with whichever generic environments are big enough to swoop through and presto!

Although it’s being distributed as Robinson Crusoe everywhere except the United States, The Wild Life drops almost everything that might identify it as an adaptation. Its Crusoe (Yuri Lowenthal) is an 18th-century landlubber who gets shipwrecked along with his dog and a couple of villainous cats on a remote island, provoking the suspicion of most of the local fauna, with the one exception being Mak (David Howard), a parrot who has always been curious about the larger world. Readers can probably fill in much of the rest on their own: Crusoe wins over the island’s seemingly unsustainable “one of every kind” animal population; the cats have lots of implied cat sex, producing more cats; Crusoe and company fight the cats. Because Stassen (who co-directed with Vincent Kesteloot) started out as a designer of ride simulators, which are still a major part of NWave’s business, Crusoe’s major feat of human ingenuity involves building a rickety water-park-like flume, which might as well be called Chekov’s 3-D set piece.

While the island itself is an un-scenic snaggletooth of beige rock—done no favors by NWave house camera style, which tends to be two-thirds empty space—the character animation is competent, especially with the gangly, bumbling Crusoe. But the dialogue is exclaimed kiddie-movie boilerplate (“Do not try this at home!,” “Let’s show them what we’re made of!,” “I think I have a plan!,” etc.), delivered by a bargain-bin English-language voice cast of first-timers and anime dub veterans, with everything explained twice over by the narration of the parrot, whom Crusoe dubs “Tuesday.” There are no captives to be rescued in this version, no cannibals—though the animals do at one point pretend to be a cannibal tribe in an attempt to scare Crusoe off, which doesn’t make any sense, given that they’ve never seen a human before. (The movie’s references to England don’t make much sense either.)

The Wild Life is just pokey and underimagined enough that grown-up viewers might find themselves begging for something deeply wrong with it, holding on to every shot of the evil pregnant cat for hope. Sadly, it never gets as bizarre as Fly Me To The Moon, which ended with the terrifying sight of Buzz Aldrin stepping out of the screen to tell children that the story never happened and is in fact impossible. It does, however, offer a weird coda of its own, in the form of an illustrated end-credits sequence that seems to be summarizing another two hours’ worth of plot, in which, among other things, Robinson Crusoe gets a girlfriend.