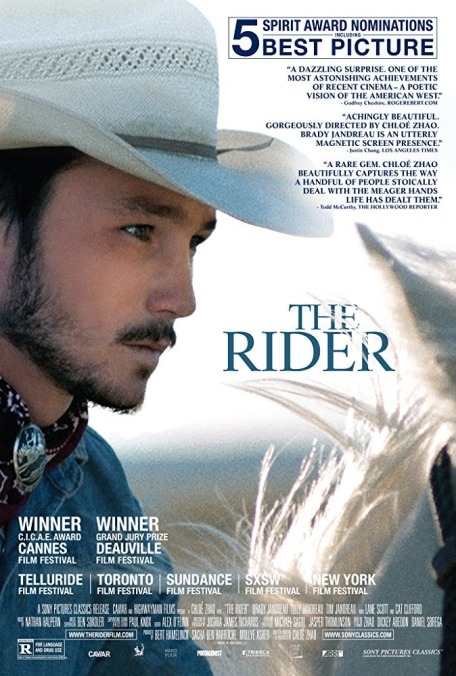

Rodeo cowboys play themselves in the fascinating The Rider

Technological innovation has actors justifiably worried that they might one day be replaced by digital avatars. (See, for example, The Congress, in which Robin Wright continues to star in action movies decades after she retires.) Lately, though, it’s starting to look as if they must also contend with a more analog threat: real people playing themselves. Three American soldiers who overpowered a terrorist on a high-speed train re-created their own heroism in Clint Eastwood’s The 15:17 To Paris, with authenticity ostensibly compensating for stiff, unnatural performances. And there are no professionals at all to be found in The Rider, which is technically fiction—the main family’s surname has been changed, for example—but more or less re-stages events that took place a few years ago, using the very individuals who had experienced them. More retroactive documentary than docudrama, it’s remarkably effective at creating a sense of verisimilitude, and these non-actors seem far more comfortable in their own skin.

That’s especially true of Brady Jandreau, a young South Dakota rodeo cowboy whose dreams of glory in the saddle were temporarily crushed, along with part of his skull, when he took a fall that very nearly killed him. As “Brady Blackburn,” whose biography closely mirrors his own, Jandreau explores the feelings of impotence and panic that consumed him during the accident’s aftermath, when doctors sternly warned him never to ride a horse again. For Brady, this is like being told never to breathe again—insupportable. Complicating matters are his relationships with his gruff father (played by his actual father, Tim Jandreau), his younger sister (played by his actual sister, Lilly Jandreau); and, especially, his best friend, Lane (Lane Scott), who—both in the film and in real life—was hurt so badly in his own rodeo accident that he’s partially paralyzed and incapable of speech. A similar fate potentially awaits Brady should he risk riding again, but maybe that’s preferable to his current living death.

Rarely has that old chestnut about getting right back on the horse after a fall been tackled so literally, or been freighted with so much genuine wariness. Director Chloé Zhao’s previous film, Songs My Brothers Taught Me, was set in the same region (in and around the Pine Ridge Reservation), and boasted the same deep understanding of its subjects/collaborators, but suffered from a general dramatic torpor. The Rider, on the other hand, achieves a nearly perfect balance between what’s engineered and what’s observed, allowing everyone on screen to embody their own messy lives while keeping them corralled to a compelling and tightly structured (if somewhat familiar) narrative. Zhao does indulge some rather blunt symbolism that wouldn’t likely have turned up in a documentary—Brady develops an issue with one hand that makes it difficult to let go of the reins, just as he struggles to let go of his fear—but mostly focuses on the fascinating details of rodeo life and this particular slice of the American heartland, with just enough psychological acuity overlaid to sustain a feeling of forward motion. Casting actors in these roles would have negated the movie’s entire raison d’être. Anyway, they can always go play a totally invented character, like Grand Moff Tarkin. Oh, wait.