There’s no artist so unconventional that a highly conventional biopic can’t be made about them. As its title suggests, Rodin takes as its subject the famous French sculptor, considered by many to have ushered his medium of choice into the modern era, breaking the “rules” almost by accident, reshaping the art form in his own image. So, naturally and ironically, this decades-spanning portrait from writer-director Jacques Doillon (Ponette, Young Werther) conforms his life and work to a safe, familiar, largely expository mold. That’s perhaps to be expected, given that it was “made in partnership with the Rodin museum,” most likely as an official commission for the centennial of his death. But it’s still quite the mismatch of content to form—a movie as ordinary as Rodin himself was extraordinary.

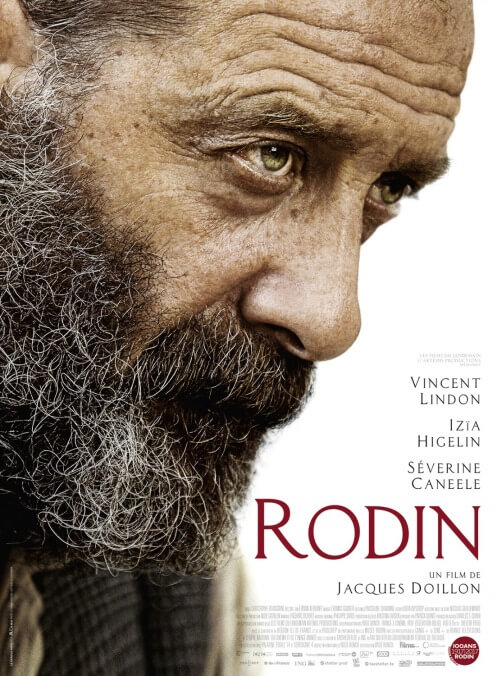

Given his skill at capturing nuances of expression, the real Auguste might at least have appreciated that Doillon found a proper model for his rendering of him. Vincent Lindon, the composed, dignified French star of The Measure Of A Man and Bastards, has an inherent seriousness that makes him an ideal fit for the role. He certainly looks the part, his haunted, piercing eyes—pools of intelligence at the center of a face half-submerged in gray hair—locking onto the entwined subjects of his appetites, as though he were trying to melt flesh and clay alike with the burning intensity of his stare. Rodin begins in 1880, when its eponymous subject, then 40 and just starting to be recognized for his work, was awarded a major commission of his own: the creation of a sculptural tribute to Dante’s Inferno for a Parisian museum. Although the building itself was never built, Rodin spent the rest of his life tinkering away on The Gates Of Hell, from which some of his most famous individual pieces, including The Thinker, originated. The movie turns the perennial work-in-progress into a through-line, periodically returning to its indefinite construction.

The other constant is a love triangle, the parallel romances Rodin maintained with his longtime companion, Rose Beure (Séverine Cannelle)—rather uncharitably depicted as a possessive shrew—and his disciple and mistress, Camille Claudel (French rock star Izïa Higelin), now regarded as a rather important artist in her own right. Rodin sparks to life a little in her company, largely because Higelin brings such a vivaciousness and volatility to the role; early scenes of the artists trading inspiration (and spit) suggest a more playful, less worshipful film. But for as much as Rodin acknowledges the imbalance in opportunity between the two—how, for example, her own nude sculptures were censored while his were celebrated—it keeps Claudel in his shadow as surely as the turn-of-the-century art world did. History dictates that the two must eventually part, and Rodin, like Rodin, suffers from her absence, to the point where one might faintly wish the film had boldly abandoned its titular subject and followed Claudel to the insane asylum to which her family unjustly, permanently committed her. (Admittedly, someone already made that movie.)

The scenes concerned with process hold a certain procedural appeal, at least for those more interested in the fine art of assembling a sculpture piece by piece than in the romantic woes of the man doing it. (When Rodin is hired to immortalize Victor Hugo, he approaches the assignment like an undercover journalist, stealing glimpses at the author while he dozes after meals and racing across the estate to his work station to commit details immediately to clay, before they fade from his memory.) But too much of Rodin unfolds from the privileged vantage of hagiographic hindsight, as though its point of view were that of a docent walking us through one of this year’s anniversary exhibitions of the artist’s work. Rodin may have known he was a master making history (he brags, in early voice-over, of elevating clay from the bottom to the top of the hierarchy of raw materials), but Doillon needn’t have made that the subtext of every scene, courting a sense of smug, present-day superiority over the squares who didn’t get his then-controversial, authentically bulbous tribute to Honoré de Balzac, which the film helpfully explains, with a parting title card, is now regarded as the first truly modern sculpture.

Often, in other words, Rodin itself looks as immobile and damnably honorary as a commemorative statue—and not one that would ever scandalize the traditionalists, the way Balzac did. At the risk of overdoing the metaphors, it also sometimes resembles a big lump of clay, what with Doillon refusing to find much of a shape, a distinct perspective, on the years of events he dully dramatizes. (Sadly, this is not one of those biopics that productively, pointedly limits its time frame, though maybe it counts as a relief that we don’t get a scene of preteen Auguste molding a likeness of his mother out of mud.) Handsomely filmed, sluggishly paced, and not very different from any Great Man tribute that conflates libido with creative inspiration, Rodin may be less illuminating than a scroll through Wikipedia. You get to see more of the work there, anyway.