Rafiki is a love story between Kena and Ziki (Sheila Munyiva), two very different but undeniably compatible teenage girls from rival political families. The fact that their fathers are both running for the same local office makes their romance fraught enough, but that’s the least of Kena and Ziki’s problems. The culture they grew up in is far more oppressive: Homosexual relationships are still illegal in Kenya, thanks to laws supported by a deeply conservative, often violently homophobic culture. Rafiki was banned in Kenya for its “clear intent to promote lesbianism,” making it illegal to even possess a copy of the film in the country. That ban was eventually lifted for a weeklong Oscars-qualifying run, but that only came after a protracted legal fight that director Wanuri Kahiu took all the way to the Supreme Court of Kenya.

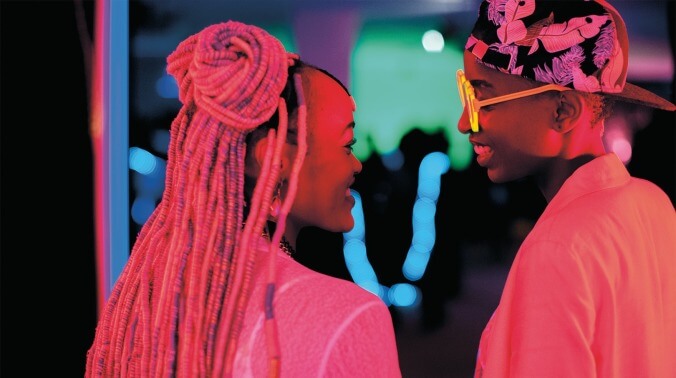

Kahiu seems to truly love her home country, and films it in deep, crisp moving shots that convey her enthusiasm for Kenya’s cityscapes and rural vistas alike. The costumes and hairstyles, particularly Ziki’s cotton-candy pink and blue locs, are similarly dynamic. Even the film’s most casual setups, like Kena’s mother’s favorite spot on the couch in their apartment, explode with pattern and color. Bolstered by an energetic African pop soundtrack, Rafiki effectively articulates the aesthetic philosophy Kahiu calls “Afro Bubblegum,” a movement that advocates for “a fun, fierce, and frivolous representation of Africa” in “work that celebrates joy.”

The tension between that aesthetic and the serious, life-and-death stakes of the story isn’t ironic, exactly—Kahiu just wants her beloved Kenya to do better by people like Kena and Ziki, dreamers who simultaneously long for and fear the wider world. Their tentative friendship is established at the beginning of the film, when Ziki tears down a campaign poster for Kena’s father, then offers to buy her a soda to apologize. The tender relationship that blossoms from there is similarly innocent, formed over blacklight dance parties and lazy afternoon hangouts, then consummated in one dreamlike, tastefully filmed night in the back of the abandoned van that serves as their treehouse/love nest.

Kena and Ziki love each other, and want to make something of themselves instead of spending their lives in the domestic drudgery in which so many Kenyan women find themselves trapped. (“Good Kenyan girls become good Kenyan wives,” as the saying repeated in promotional materials for the film goes.) Practical, tomboyish Kena—“My body is allergic to dresses,” she says at one point—wants to become a doctor. Feminine Ziki is a free spirit who doesn’t care about school and dreams of traveling the world, where she’ll “go to all those places where they’ve never seen an African, and just show up there and be like, ‘Yo, I’m here and I’m a Kenyan from Africa.’” Beyond that, they haven’t really thought things through. So when Ziki, emboldened by love and the invincibility of youth, starts taking risks by showing affection for Kena in public, the busybodies in their neighborhood are more than happy to burst their puppy-love bubble.

In some ways, Rafiki recalls Nijla Mu’min’s 2018 film Jinn, which also superimposes a unique, beautifully realized point of view onto a conventional coming-of-age story. Also like that film, Rafiki adds to the mix complicated family dynamics—at least, between Kena and her divorced parents; we don’t know much about Ziki’s family—which become superfluous before being dropped entirely as the romance takes center stage. More than anything, though, it recalls Shakespeare’s classic Romeo And Juliet, in setup if not in conclusion. That goes back to the short story upon the film was based, Monica Arac de Nyeko’s prizewinning “Jambula Tree,” set in the neighboring country of Uganda, where life is even more difficult and dangerous for LGBTQ people than it is in Kenya. But if there’s one thing we know about Shakespearean story tropes, it’s that they can be applied to any time, place, or culture and still remain relevant. And regardless of where they’re from, people are people, and love—and light, and color, and music—will find a way.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)