Like a lot of film versions of classic modern plays, Tom Stoppard’s 1990 adaptation of his meta-theater masterpiece Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead documents two eras. The play remains to some extent a product of its time: a standout from a stretch of the 1960s when the stage was dominated by British dramatists and arty absurdism. The movie too seems like an artifact. Stars Gary Oldman and Tim Roth look so young and so vital, and the production as a whole has a classiness and solemnity in keeping with the arthouse hits of the late ’80s and early ’90s. The provocative radicalism of the original was rendered as something staid, tasteful… almost normal.

Stoppard started working on this idea of side-stage Shakespeare early in his playwriting career, and presented a fairly full version of the play in 1966 at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. From there, productions opened in London and on Broadway, winning awards and pulling in surprisingly robust box office, from a theater-going public growing accustomed to post-modernism and abstraction—and perhaps appreciating an offbeat play that was at least connected to something traditional. Even playwright/critic William Goldman, who dubbed shows like Rosencrantz & Guildenstern “snob hits” in his acerbic 1969 book The Season: A Candid Look At Broadway, admitted that he thought Stoppard’s work was “terrific” and “the undisputed dramatic triumph of the year.”

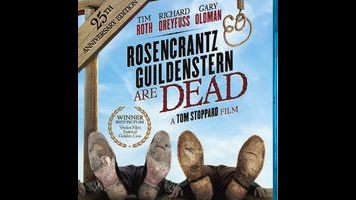

That sense of discovery doesn’t exactly carry over to the movie version, which Stoppard admits he was reluctant to make in the first place. (“They’re plays,” he says of his work. “What is the necessity for making them into films?”) The new Blu-ray of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead adds over three hours of interviews with Stoppard, Roth, Oldman, and Dreyfuss—all recorded a while back for an earlier DVD edition, judging by their low video quality—and in them Stoppard admits that there’s nothing especially cinematic about this material. In fact he says he had to be reminded by his cinematographer Peter Biziou to move the camera every now and then. Rosencrantz & Guildenstern won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1990, beating out Goodfellas, which Stoppard laughs off as a ridiculously short-sighted outcome. Cinema in the ensuing decade—even arthouse cinema—looked a lot more like Scorsese than Stoppard.

Oldman, though, astutely notes in his interview that there’s a clear directorial presence in this Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, evident in the way Stoppard places the camera at unusual angles to emphasize his skewed perspective on Hamlet. The movie never looks “stagey,” except for when it’s repeating Shakespeare’s scenes verbatim. The rest of the picture looks like it’s been wedged into various waiting areas, which are largely unoccupied while the main players are otherwise engaged. Plus, although Stoppard has a gift for wordplay to rival The Bard—seen most plainly in the sequence where Rosencrantz and Guildenstern try to decide if their friend Hamlet is “melancholy,” “mad,” or “morose”—he also breaks up the flow of chatter with bits of silent comedy, some of which are original to the film. A long sequence where the traveling actors pantomime a sword-fight is a brilliant piece of both theater and cinema, using editing and blocking to reveal the artifice behind an act of violence.

Still, the main reason to watch Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead now—beyond getting the gist of a important piece of theater history—is to watch Oldman and Roth play off each other like a couple of spry young athletes, rapidly batting Stoppard’s dialogue back-and-forth. As a record of the play, the movie version of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern doesn’t have the same crackle that people who saw some of the original productions describe. But as a record of two of British acting’s best? This film’s a reminder of why Oldman and Roth were such a big deal in 1990, and why they still play even their supporting parts as though they’re the stars of the show.