Feeling an intimate and honest connection with a comedian isn’t always necessary for observational comedy to succeed; after all, the most widely heralded observational comic, Jerry Seinfeld, is consistently closed-off onstage. But Seinfeld is the exception that proves the rule, since for the most part, observational comedy works because it not only allows us to explore universal feelings of embarrassment, lust, and insecurity, but delivers a message that’s filtered through a distinct and captivating voice. Shlesinger’s comedic voice and delivery hardly feels unique, and it renders her already undercooked observations about the behaviors of men and women all the more disappointing.

Shlesinger hits every predictable beat in terms of observational comedy that’s focused on how men and women are different, either in their social interactions, their romantic feelings, or their thought processes. She muses on how women are always cold, and yet never want to carry a jacket. She spends an exorbitant amount of time talking about how women are walking contradictions; “girl logic,” as she coins the female thought process, is just “contradiction wrapped in a bow.” Other popular targets that are peppered throughout the set: silk blouses, pumpkin spice lattes, and a lengthy diatribe about how women are addicted to Pinterest, or as she calls it, the Call Of Duty for women. These observations are rooted in perceived gender roles, which isn’t inherently a bad thing. Observational comedy is a lot about taking universal truths and making them personal and relatable, and there is certainly comedic territory to be explored in how men and women interact with one another, and how they often exaggerate their traditional gender roles in certain situations. But Shlesinger’s insights aren’t particularly inventive or unique, and the result is a flurry of jokes that would feel at home on the most rudimentary network sitcom, where painting in broad strokes makes for accessible and inoffensive television.

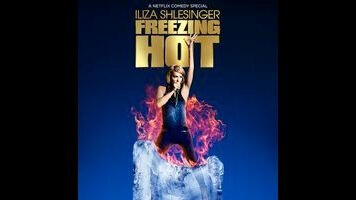

Such uninspired comedy permeates the majority of Freezing Hot, which is a shame, because every now and then Shlesinger finds a compelling voice that scathingly and insightfully critiques both current cultural values and the ludicrous nature of prescribed gender roles. In the midst of a rant about how women obsessively plan their weddings on Pinterest, she takes a long detour and paints a picture of a bunch of friends organizing a lunch together. She lambastes the one woman who always suggests tapas, and skewers the sense of privilege her and her friends feel; in a mock Valley Girl voice, she tells a waiter, “We’re in a rush because we’re entitled.” Shlesinger only occasionally infuses her set with cultural critiques, but they represent the funniest and most honest moments of the special. When she’s talking about all the crazy things women do, and then pauses to admit that, okay, men do crazy things too, like “rape and war,” it’s a brief look into what Shlesinger’s comedy could be. It’s the honest and aggressive tone that she touts in Freezing Hot’s opening. She extends that criticism to the culture at large too, specifically taking aim at beauty products and advertising. She laments how such products trade in the “currency of women’s insecurities,” an insight that, while not exactly fresh, at least boasts a purpose; coupled with Shlesinger’s manic delivery, it lends the subsequent series of jokes about ludicrously named makeup products (Flirty Girl, Bad Gal) a sense of urgency and poignancy.

Such moments of energy and viciousness are few and far between. For most of her set, Shlesinger is satisfied to settle for easy punchlines about the behaviors of men and women. Freezing Hot is filled with boilerplate observations that lack substance and insight, a fact only accentuated by Shlesinger’s style of delivery, which favors repetition and halfhearted callbacks. If War Paint was a promising, if fitful, debut special, then Freezing Hot is evidence of a comedic voice still in development. Shlesinger wants to have her cake and eat it too, interrogating the absurdity of traditional gender roles while also using those same presumptions to craft simplistic, predictable punchlines.