In 1984, a 14-year-old Lolita Shanté Gooden recorded “Roxanne Speaks Out” (later renamed “Roxanne’s Revenge”) over beats from the UTFO B-side “Roxanne, Roxanne” outside the Queensbridge housing projects where she was living. She was already a known name on the freestyle scene, taking on amateur rappers twice her size and age. But from the moment that “Roxanne’s Revenge” hit the airwaves, Gooden became Roxanne Shanté, a female MC with a harsh bite and even harsher flow. Her single spawned the Roxanne Wars, a series of rivalries between Shanté and various rappers that produced the most answer records in the history of hip-hop. By the mid-’90s, Roxanne Shanté had all but receded in the cultural memory, but her style and charisma had left an undeniable mark on a burgeoning genre and the female MCs who would rise to rule it.

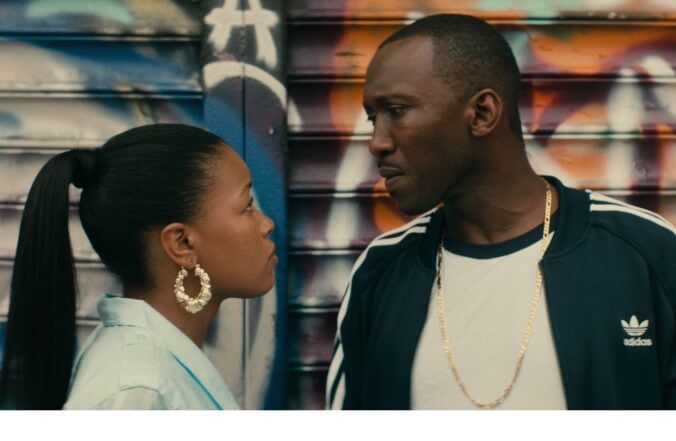

Shanté’s relatively obscure story is perfect grist for the trad-biopic mill. But with Roxanne Roxanne, writer-director Michael J. Larnell makes the inspired choice not to primarily focus on her rap career, instead acknowledging it as just one aspect of her turbulent life and eschewing many of the genre’s tired tropes in the process. Roxanne Roxanne mainly follows Shanté (Chanté Adams, in an impressive feature debut) off stage: She helps raise her three young sisters while her defeated mother, Peggy (Nia Long), slips into alcoholism and depression, hangs out with her friends past curfew, and gains the attention of older drug dealer Cross (Mahershala Ali), with whom she eventually begins a relationship. When Shanté becomes a literal overnight sensation, Larnell highlights her enthusiasm and pride, but as she rises in stature, he leaves most of the music-biography stuff—studio sessions, media coverage, and various beefs (real or otherwise)—in the background. Music is just another world Shanté has to navigate, even if it’s one where she ostensibly reins queen.

By shaping Roxanne Roxanne as a character profile, Larnell accentuates his actors’ performances and crafts a nuanced community portrait, two strengths exhibited in his delightful first feature, Cronies. He frequently frames Adams in close-up, allowing her to communicate her character’s complex emotional makeup, vacillating between steely braggadocio and teenage vulnerability often in the same scene. Federico Cesca’s cinematography and Kama Royz’s costume design are largely responsible for the film’s faded-Polaroid period aesthetic, but Larnell captures the intimate vibe of the Queensbridge projects and the hip-hop community through un-showy long takes and long shots. Roxanne Roxanne successfully conveys the contours of a neighborhood, complete with good and bad elements, but mostly filled with people making an effort amidst constant disappointment. It provides a proper emotional foundation for scenes designed to jerk tears, like when Peggy realizes her fiancé stole her savings money on the day the family is supposed to move. Roxanne Roxanne rarely becomes maudlin for its own sake, because Larnell provides a context for the daily, mundane tragedies that pervade Shanté’s life.

Elliptically structured, Roxanne Roxanne jumps forward in the chronology without obvious time stamps or historical markers. In the film’s best scene, Larnell illustrates the thin line between harmony and chaos in a triple match cut between Shanté throwing her head back in ecstasy while losing her virginity, to her crying out in pain from giving birth, to her being dragged across the floor by her ponytail. But Roxanne Roxanne’s scrapbook approach to Shanté’s story has some disadvantages, too, especially when the film tries to tie up various loose ends in the homestretch. Larnell’s script tidies up messy interpersonal relationships; a tearful monologue about her robbed childhood that all but “solves” Shanté’s tumultuous relationship with her mother. Moreover, Shanté’s abusive relationship with Cross, though harrowing and true to life, suffers greatly under Larnell’s compressed style. Ali brings swagger to the performance, and it’s compelling to see the paternal energy cultivated in Moonlight dragged in a more menacing direction. But the script renders him a generic villain in an otherwise subtly shaded ensemble. Plus, as much as Larnell strenuously avoids biopic clichés, Roxanne Roxanne does occasionally succumb to some egregious Walk Hard tendencies, most notably when it’s revealed that the young kid from the block bugging Shanté turns out to be Nas.

With producing credits by Shanté herself (as well as Pharrell Williams), along with an original score by RZA and a strange cameo by former Beastie Boy Adam Horovitz, Roxanne Roxanne sports plenty of hip-hop authenticity, but it stops short of telling a hip-hop story. Those who want a full account of the Roxanne Wars will inevitably be disappointed, as Larnell writes around key elements of the period—the formation of the Juice Crew, Shanté’s rivalry with The Real Roxanne, or KRS-One’s foray into the diss frenzy. But Roxanne Roxanne’s insights about rap as a mode of self-expression go beyond insider industry tales. It’s romantic that Shanté supposedly recorded “Roxanne’s Revenge” in between laundry cycles. It’s telling that her career blossomed from those circumstances. She might toss off rhymes in between her chores, but when she opens her mouth, everyone in the room stands up to take notice.