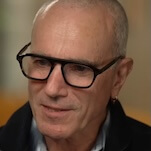

Every film, even Human Centipede III: More Shit, aims to unveil some sliver of humanity. However, most movies are not as explicit about this pursuit as A Pigeon Sat On A Branch Reflecting On Existence, Swedish director Roy Andersson’s poignant and sardonic conclusion to his trilogy “about being a human being.” (The previous two installments are Songs From The Second Floor and You, The Living.) Featuring non-professional actors and strung together by droll vignettes, the movie is a series of moments that captures humanity in all states of existence—despondency, euphoria, ennui. Winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival last year, as well as the recipient of this year’s unofficial award for best title, Andersson spoke to The A.V. Club about his career in making advertisements, not wanting to be part of a cynical world, and the immeasurable importance of generosity.

The A.V. Club: The film plays so well with a crowd, laughing together in harmony. It’s hard to imagine the same quality experience if watched alone on a computer screen. When making your films, do you think about the value of an audience, or should the film simply work no matter the situation?

Roy Andersson: I always want the former. Sometimes it succeeds, sometimes it doesn’t. In Sweden, we had good results. I have had many signs that the film functions very well when watched alone. We had Lana Wachowski visit us here in Sweden three and a half years ago. And she said she saw You, The Living in a small, small theater in Chicago and laughed a lot. Her will to make movies came back at that time.

AVC: Does your will to make movies ever wane?

RA: No, no, no. It has increased lately. I have already started to line up another project, which I’ll hopefully shoot this autumn. The title will be One Thousand And One Nights, inspired by the Persian fairy tales. This is the fourth part of the trilogy. I just joke about that, but we should keep that joke.

AVC: You’ve mentioned in the past how this trilogy of yours is about what it means to be a human being. And so, what does it mean to you?

RA: Sometimes people ask me, “Hello Roy. How are you?” And I want to say all the time, “It’s interesting.” Existence is always interesting for me. Sometimes you can be sad or happy, but it’s an interesting treasure to be alive, to be human.

AVC: Do you see yourself as someone who is cynical or optimistic?

RA: I’m optimistic. Okay, sometimes I’m accused of being cynical. But it’s not true. I don’t want to be. Sometimes it’s necessary to be a little cynical—to intensify the dialogue, the discussion. But without optimism it would not be worth it to be alive. It’s nice that we have that side of us. As human beings we have tools to survive, like humor. Humor is a fantastic survival tool. But optimism and pessimism are two sides of the same coin in some sense. I just prefer the side that’s optimistic.

AVC: Why do you think most people appear cynical?

RA: Most of us are not optimistic all the time. I think every man here on the planet needs hope. I don’t want to belong to a part of humanity that is pessimistic. I’m not a misanthrope; I’m a philanthrope.

AVC: Have you ever lost hope in making movies or become disenchanted with the medium?

RA: I had a big success when I started my career. But my second feature [1975’s Giliap] was a flop, economically and critically.

AVC: Do bad reviews pain you?

RA: Yeah, but I was aware of the fact that some scenes in that movie are not good. So the criticism was deserved. But, on a whole, I must say it’s a pretty good movie. I was in the hands of another producer at that time. I have the power of producer now, but not then. That situation forced me to direct bad scenes. I didn’t lose hope because of it, but it was a very hard time. I was kicked out of the area of filmmaking, because no producer wanted to work with me. The only people that called me were on the advertising side. So I made ads for more than 20 years.

AVC: Why did advertising call you?

RA: At the time, the Swedish Film Institute was placed in a very professional studio. The professional people there shared the same screening room as we students used. So they saw my student films, and saw some talent. They asked me to make a commercial, and it was a big success.

AVC: How does a project come to you? Do you have a single lightbulb moment, or is a more difficult process?

RA: My main source is daily life. Watching people and thinking about them when you are on a train or walking around. You can’t be a filmmaker if you aren’t interested in people and make fantasies about them. But painting and art history has influenced me a lot, as has film history.

AVC: Do you think film is the ultimate art form to express your ideas about humanity?

RA: When I go to a museum, people can be standing in front of a single painting for over a half hour. And there are so few films in history that have that quality. One part of my ambition is to lift the visual qualities in filmmaking so that we can reach the same level as paintings. Maybe it’s a little too ambitious. I don’t want to sound like I’m bragging.

AVC: What movies have achieved that level?

RA: French movies in the ’30s and ’40s. The film noir. Some early Humphrey Bogart movies have that atmosphere. One reason why movies are more superficial than paintings is because they cost a lot of money to make. I have been forced to make something superficial. I’ve made over 300 commercials, and I think five of them are pretty bad and I’m ashamed of them.

AVC: What’s the reasoning behind the white makeup in your films?

RA: [Laughs.] Well, I want the people to be universal. I was once deeply stimulated by naturalism and realism in movies. I was a big fan of Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves, for example. But when I had worked with the producers on my earlier films in the realistic style, I got fed up, and thought I didn’t want to make any more movies. I just wanted to become an author. This was true up to the moment I realized maybe I should dare to go over to abstract style, inspired by Federico Fellini in Italy. I found this style to be a fantastic release. From that point on, I’ve made movies in what I call an “abstracted style.” To that style the white makeup belongs, along with the colors and the environment. It’s my search for “timelessness.” Like the clown—he’s representing all of us. There’s this tradition in Noh Japanese theater where the actors wear white masks. When you quote Shakespeare with a white mask on your face, the intensity of the dialogue increases. “To be or not to be”—to say these words behind the mask is stronger than without it.

AVC: Is there a shot or sequence in this film that you believe best captures humanity?

RA: I have one favorite. It’s a very simple scene. It’s a man that’s pretty old, and he’s alone sitting in the restaurant as they are cleaning up. It’s closing time, and he’s trying to contact the waiter. And he says, “I understand one thing. I have been greedy and ungenerous all my life. That’s why I’m unhappy.” It’s a key scene for me. Generosity makes you happy.

AVC: Have you not been generous enough in your lifetime?

RA: Not enough. I could have done more.