Ridley Scott entered the new millennium in trouble. Though he directed a pair of sci-fi classics early in his career and hit another peak with Thelma & Louise in 1991, by the end of the ’90s he was coming off a streak of flops: the interminable 1492: Conquest Of Paradise, the largely forgotten White Squall, and the future hacky punchline G.I. Jane (actually the most successful of the group, while also helping to curtail Demi Moore’s career as a leading lady). Today’s Ridley-loving film geeks may not recall, but Scott’s rep at the time was that of a slick visual stylist with an uneven-at-best filmography. (Looking back, he may also have been nursing an obsession with boats.) Then, in the spring of 2000, he released Gladiator, and it seemed to imbue his uneven work with a more pugnacious and prolific spirit that continues to this day. Starting with that Oscar-winning hit, he would go on to make nine movies in the space of about 10 years. Five of them starred Russell Crowe. Scott made more Russell Crowe movies during this period than movies of any kind in the ’90s.

The role of Max Skinner does represent an actorly stretch for Crowe, at least partially in a way that seems self-designed. It’s easy enough (if tedious) to picture Crowe as a gruff and/or merciless businessman who softens up by reconnecting with his late uncle’s dilapidated but charming vineyard. But that’s not exactly how he plays Max. He’s less ’80s-slick hot-shot or fearsome boss than Cary Grant smoothie. Thanks to a combination of readjusted time-period expectations and Crowe’s attempt at droll Englishness, Max at times comes across as downright effete. Crowe isn’t bad, exactly—it’s a genuine change of pace for him, making a game attempt at emphasizing the comic elements of a movie where “comedy” more often means “not explicitly tragic”—but it’s not an easy fit, either. That could be because Ridley Scott’s grasp of comedy is somewhat technical, to be kind. It’s not that the sorta-witty dialogue or occasional pratfalls are mistimed or badly framed; Scott just seems more interested in his star’s face than any light shtick that might surround it. Atmosphere isn’t antithetical to comedy, but it’s not exactly first priority, either, and Scott feels most plugged into A Good Year in an early sequence where Max wanders around the grounds of his uncle’s estate, as flashes of childhood memory echo around every corner. Not exactly a laugh riot.

It doesn’t need to be—but the movie isn’t a swoonworthy romance, either. Marion Cotillard plays Max’s nominal love interest, and they go on their first and only proper date roughly 85 minutes into the movie. As if making a bid to render the film as authentically, which is to say stereotypically, French as possible, the story instead spends a lot of time with the character of Max’s hot cousin. A Good Year is, simultaneously, a relatively sophisticated example of its type and a checkbox for Scott and Crowe unlikely to be revisited. (Don’t watch for A Good Year: Covenant in another 20 years, in other words.)

Crowe and Scott played with another very of-the-moment subgenre when they made Body Of Lies, one of those 2000s-era action-dramas of murky geopolitical intrigue, inspired by the misbegotten U.S. involvement in the Middle East. It’s more of a vehicle for Leonardo DiCaprio, unsurprising in that he was (and remains) one of the biggest stars in the world, but also odd because Crowe’s character Ed Hoffman, DiCaprio’s CIA boss, pops more. Odder still, he does so with a normie vibe: middle-manager haircut, often taking calls from his rogue employee while toting his kids around, responding to a question about his overseas flight with, “It was fine. I watched that, uh, Poseidon.” This pre-visioning of Crowe’s character-actor future as a guy behind the guy and/or the guy in the chair, as seen in movies as disparate as Land Of Bad and The Mummy, becomes the most memorable facet of an otherwise forgettable run-through of morally uncertain modern espionage.

As much respect as Scott commands as a stylist, and as atmospheric as his best movies are, he’s not exactly one to soak in the vibes like Michael Mann, or his late brother Tony; it’s easy to imagine either of them making a version of Body Of Lies that would be both more visually memorable and more viscerally exciting, transcending the weaknesses on the page. Scott has a story-first efficiency that suffers alongside any screenplay weaknesses. Hell, even when the story is good, Scott often takes a workmanlike approach. That’s probably part of the reason the rock-solid American Gangster (2007) hasn’t grown in reputation as much as the movies it echoes, like The Departed (cat-and-mouse involving corrupt cops and community-beloved crooks) or Heat (cat-and-mouse involving two movie stars who only really share a single meaty scene). If anything, the movie is even more methodical than supersized crime dramas from Mann or Scorsese, with both Denzel Washington (as a heavily fictionalized version of low-profile drug kingpin Frank Lucas) and Crowe (as Richie Roberts, the cop who helps bring him down) playing their characters closer in register to Neil McCauley than Vincent Hanna.

Scott and Crowe find a surprising groove in the movie’s lack of overt electricity. (Washington brings his own in that regard. He’s like a portable generator.) It’s probably Crowe’s least elaborate performance of his five Scott projects: no big heroics, no major physical transformation, little movie-star flash, not even much of a character arc. Yet he embodies a doggedness that, at times, seems to be all Richie really has, both at his job and materially speaking. (In the movie’s telling, Frank isn’t eventually busted because of innovative detective work, but because he makes the mistake of wearing an uncharacteristically ostentatious coat out in public.) In American Gangster, Crowe more effortlessly achieves what he seems to have to will into existence for Body Of Lies: the unfussy ease of a veteran character actor. It almost reads as a mirror of Scott’s movie-a-year work ethos. Do the work, don’t worry about glamor, box office, or Oscars.

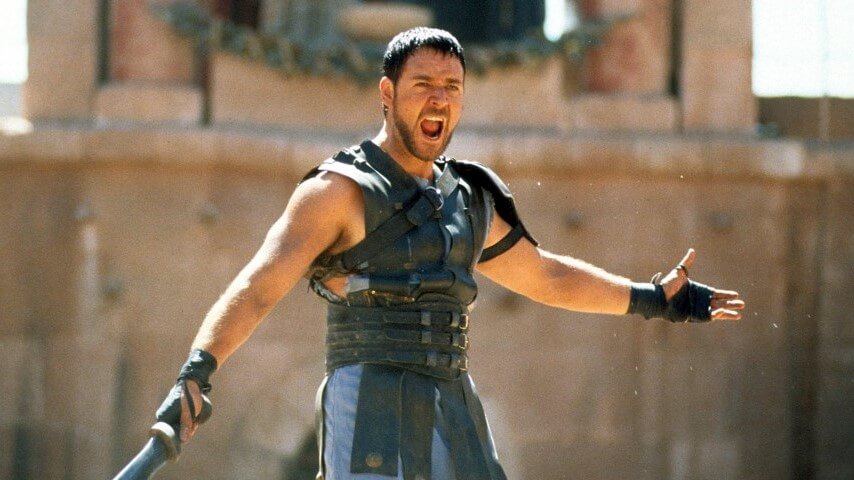

Ironically, the no-fuss semi-prestige crime picture ultimately became a bigger hit than Crowe and Scott’s final movie together. More than their three interim projects, Robin Hood (2010) functioned as a straightforward Gladiator reunion: Summer release, a decade after their initial triumph, historical action, lots of guys getting pulverized in battle… it’s all there, except for the magic. To be clear, Gladiator isn’t all that magical to begin with. It’s a handsomely made old-fashioned epic, with Crowe (and, in a different way, Joaquin Phoenix) providing the flashes of contemporary nuance. Crowe reconciles the brutality and showmanship of his slave/fighter role by leaning into his yearning for the family robbed of him by war. An old sympathy trick, to be sure, but Crowe has enough latent gentleness (again, see the two big movies that sandwich Gladiator on his CV) that the movie never feels like it’s making excuses for us to cheer his savagery. Despite Scott’s own brutal showmanship (and, again, workmanlike approach to it), that aspect of the story sometimes feels like sly, even rueful commentary on the turning of violence into entertainment.

In its way, Robin Hood is a bit lighter than Gladiator—anyone who enjoys dudes getting owned by hails of arrows and, at one point, bees should have an okay time, speaking of entertaining violence—but only by half-measures, enough to reduce its gravitas but no competition for the many genuinely fun versions of this story. Just as Gladiator is distinguished by Crowe’s star turn, Robin Hood is limited by his glumness in the title role, as well as its presumptuous origin-story approach to the character. Surrounded by a strong cast (Cate Blanchett, William Hurt, Oscar Isaac, a young Léa Seydoux, the underrated Kevin Durand), Crowe recedes into his brooding, commanding less screen time and just plain less of the screen in general. You can almost see him, after a decade as a full-on movie star and more relaxed turns in Gangster and Lies, scheming to resign from his old position. He wouldn’t banish dourness from all his future films, but many of Crowe’s post-2010 performances often seem to relish no longer staying in fighting trim, no longer having to justify some traditional idea of heroism. It’s as if his 2000s-era Scott movies confirmed his preference for character acting, regardless of his gladiatorial success. Obviously there are good story reasons that he doesn’t appear in Scott’s new Gladiator II, but beyond that, Crowe’s current proclivities as a performer don’t particularly sync up with this material, either, even with in its darker moments. Or rather, Crowe seems more likely to take the type of role his American Gangster co-star Denzel Washington has in the new movie: playfully hammy, delightfully himself. In some ways, his acting has inched closer to the jovial weirdo he once played on an ill-regarded episode of Saturday Night Live.

Scott, however, never really lost his taste for large-scale battle sequences: balls of fire and hails of arrows and those Gladiator-style undercranking effects. He’s continued his productivity without Crowe; Gladiator II is his tenth movie since their last film together, 14 years earlier. During this period, he’s done sci-fi (with and without horror), a Biblical epic, another medieval drama, some quasi-biopics, and the hard-to-classify The Counselor—not all big-canvas stories, to be sure, and perhaps better when he’s able to dig around for something smaller and stranger, exactly what’s missing from a mega-production like Robin Hood (or Gladiator II). Sometimes the versatility of Scott’s talents overwhelm his taste. Despite all those Crowe movies, his best movie of the 2000s doesn’t feature his muse at all: It’s the clever, affecting con-man dramedy Matchstick Men, nary an arrow to the neck in sight. Scott’s craftsmanship, his eye for the shine or scuff of surfaces, works perfectly for a movie about different forms of deception, without forcing the actors—Nicolas Cage, Alison Lohman, Sam Rockwell—to compete with the pageantry.

Though there are highlights in his five movies with Crowe, it may be that Scott’s style isn’t especially well-suited to long-standing collaborations with the same actors. Well into his 80s, he seems invested in both size and quantity; quality, well, that’s for the Scott-heads to debate. Crowe remains famous, and a welcome presence in a variety of genres. But more than ever, his movies with Scott seem to have left him comfortable with getting small.