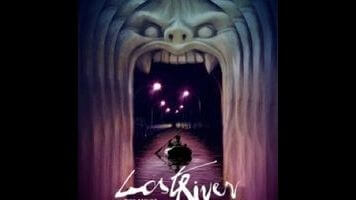

Ryan Gosling’s Lost River blurs the line between homage and theft

Fame, fortune, good looks, a thriving acting career, and a pretty great meme are evidently not enough for Ryan Gosling. He also wants to be David Lynch. And Harmony Korine. And Terrence Malick. And Dario Argento. And the driver of his hypnotic Drive, Nicolas Winding Refn. Lost River, Gosling’s first feature as a writer and director, swipes atmosphere, motifs, music cues, lines of dialogue, even specific shots from all of those filmmakers. It’s less an original vision than a wild collage, its creator cutting and pasting from the cinema that haunts his dreams. Imitation is a healthy, productive stage of creative growth; many young artists spend their early years fusing components of the work they love, tinkering with the equation until the results resemble something new. But Lost River displays almost no distinctive personality of its own. The film proves that Gosling has refined taste in movies, and that he’s a quick study, but not that he has much to say as an artist. Not yet, anyway.

Which is not to imply that there’s nothing to admire in this grotesque funhouse pastiche, a much less catastrophic folly than early reviews have indicated. Even when derivative, Gosling’s images—of a raging house fire, of boarded-up buildings with overgrown lawns, of cars careening into the night—are often apocalyptically striking. The actor-turned-filmmaker shot his debut in Detroit, which he reconfigures, Beasts Of The Southern Wild-style, into an exotic, half-flooded ghost town. (The original title, How To Catch A Monster, hinted more explicitly at the film’s undercooked mythology.) Here, the streets are empty at all hours, televisions show nothing but old cult movies, and just about everyone answers to a one-or-two-syllable name, like Face or Rat or Bully. This includes our hero, Bones, a driftless dreamer played by Iain De Caestecker, the sensitive British tech wiz from Agents Of S.H.I.E.L.D.

Bones, who Gosling himself might have portrayed a decade ago, spends his days stripping copper from vacant properties. (A sly acknowledgement of the filmmaker’s own artistic scavenging? Probably not.) By night, he courts the aforementioned Rat (Saoirse Ronan), the moody girl next door, presumably nicknamed for the pet rodent she dotes on. This nascent romance helps distract from the faintly incestuous chemistry the young man shares with his mother, Billy (Gosling’s Drive co-star Christina Hendricks), who does a different kind of stripping to help support Bones and his little brother. Talked into taking a loan she shouldn’t have qualified for, Billy is now in danger of losing the family home. Insomuch as Lost River is about anything beyond its own crazy-quilt embroidery, it’s about how banks have fed on the desperation of homeowners, reducing once-vibrant communities to deserted residential wastelands. Gosling’s interest in the subject, however, seems chiefly cosmetic. He sees a beauty, or at least a chic grandeur, in urban decay.

For a while, there’s fun to be had in playing spot the reference. An early shot of the redheaded Hendricks lifting her child skyward is basically a direct homage to The Tree Of Life. (Gosling, like Malick, has made a bravely uncommercial film that seems destined to scandalize viewers drawn to nothing but the household name on the one-sheet.) Italian horror is another clear touchstone: The music, by frequent Refn collaborator Johnny Jewel, nods overtly to Goblin’s iconic Suspiria score, and Rat’s mute grandmother, perpetually bathed in the flicker of an old projector, is played by aged Black Sunday star Barbara Steele. Meanwhile, Billy starts performing at a club that specializes in giallo burlesque; her first routine, for a crowd apparently composed mainly of Fangoria subscribers, finds her pretending to slice off her own face.

There are villains, too, both plainly modeled on iconic figures from other movies. As the sinister bank manager who runs the Grand Guignol gentlemen’s club, Ben Mendelsohn appears to be channeling not one, but two characters from Blue Velvet: He spouts lines originally written for Dennis Hopper, and does his own take on Dean Stockwell’s big scene, simply trading lip-syncing for karaoke and Roy Orbison for Johnny Cash. The other heavy is a tattooed neighborhood kingpin played by (wait for it) Doctor Who’s Matt Smith. He’s introduced riding around town on a throne affixed to his car, bellowing, “Look at my muscles, look at my muscles.” James Franco was apparently unavailable.

On and on goes this parade of secondhand pleasures, which Gosling leads like a Blu-ray collector excitedly, impatiently rifling through his own stash. There’s a certain charm to his hero worship, and a sporadic lyricism to his staging, especially in moments when his characters are just cruising down the quiet avenues of the Motor City. At the very least, the director has made a better, more fascinating spiritual sequel to Drive than Only God Forgives. Yet all the ostentatious, recycled weirdness grows wearisome as the movie plods on, mostly because the first-time filmmaker hasn’t written any characters, just mannequins to arrange in his art installation piece. If the negative reaction to Lost River doesn’t squash his ambitions, Gosling could become a truly interesting director; he certainly has the right mixture of moxie, fearlessness, and an expert eye. What he most needs is a better impetus to move from one side of the lens to the other—a goal, in other words, beyond simply impersonating his idols.