Sad timeliness provides The Zookeeper’s Wife with more power than it earns

The Holocaust drama The Zookeeper’s Wife is handsomely made, well-acted, and lacking in much nuance. But what would have once been a staid history lesson—the expectedly upsetting elements numbed by the cinematic missteps and the passage of time—now has an urgency that makes it more devastating, even more likely to bring an audience to tears. With xenophobia rampant and Nazi rhetoric inching its way into the mainstream, the events Niki Caro’s directorial effort depict somehow don’t seem so far away. But the visceral reaction it elicits also feels unearned given its surface-level treatment of the subject.

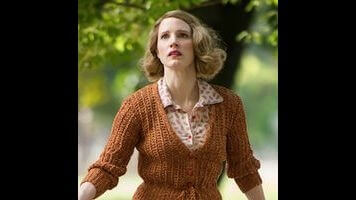

Adapted from a work of nonfiction by Diane Ackerman, the plot follows Antonina Żabiński (Jessica Chastain) and her husband, Jan (Johan Heldenbergh), living an idyllic life in 1930s Warsaw, where they run the zoo. Caro and her cinematographer Andrij Parekh paint the pre-war period in bright colors, but smoke and spilled blood soon sully the pastoral scene, and that juxtaposition accounts for the movie’s most striking imagery. Eventually Antonina and Jan begin hiding and rescuing Jews, even as the Nazis commandeer their facility.

Jan is quicker to recognize the danger and injustice encroaching upon him and his wife, and comes off as the more traditionally noble of the couple. Antonina, on the other hand, is something of a puzzle, and tightening the action around her might have proved more fruitful. She is preternaturally gifted with the creatures in her care, but isolated from the humans around her. Affecting a serviceable Polish accent, Chastain imbues her character with a childlike quality that conveys, in turns, both naiveté and innate goodness. This is a paradox worth exploring, and one that Chastain is keen to illuminate in her measured, admirable performance. Unfortunately, Caro and screenwriter Angela Workman are working on too large a scale to present a fully rendered study of Antonina—or anyone else, really.

In trying to cram the whole of the Żabińskis’ story into two hours, The Zookeeper’s Wife can’t help but shortchange character development, and it often feels like key details have been left on the cutting-room floor as time jumps forward. For one, the disturbing attempts by the main Nazi (Daniel Brühl, essentially reprising his role from Inglourious Basterds) to sexually coerce Antonina feel like little more than a plot device, and an unexplored one at that.

However, the most egregious oversight is in painting the Jews being saved in broad strokes. They are for the most part nameless, silent sufferers, and even those who are meant to be friends with the Żabińskis prior to the German occupation are hardly given identifiable traits aside from being Jewish. Antonina bonds with a girl, Urszula (Shira Haas), but she is defined solely by her abuse at the hands of Nazi soldiers and the resulting trauma. It’s a troubling trend, especially in a movie that—by virtue of its subject matter—uneasily and perhaps unintentionally equates those taken in by the couple to animals. There’s also a certain kitschiness to how Caro employs the zoo’s nonhuman population, even though she does so with the same affection her heroine possesses. At times, Antonina almost comes across as a Doctor Dolittle figure, cuddling cute lion cubs, saving a baby elephant, and riding her bike around the zoo, a camel following close behind.

The Zookeeper’s Wife can be bluntly effective and affecting. Take, for instance, the wrenching sequence where a Passover seder is performed in secret as the Warsaw ghetto is burned. But its power largely comes from its unfortunate immediacy. If it didn’t seem so timely, it would simply be rote and unchallenging. It’s vital to remind audiences of the Holocaust’s horrors, but maybe a film that’s doing that shouldn’t look so pretty.