Saint Laurent is an imperfect but often poetic take on the life of a fashion mogul

Yves Saint Laurent was said to smoke as many as seven packs of cigarettes a day, typically Peter Stuyvesants. He died of cancer, but brain cancer, not lung cancer. Nobody told him he was terminally ill. The diagnosis was kept secret from him by Pierre Bergé, his partner. Instead, Saint Laurent lived the last months of his life much like like the months and, presumably, years before them, chain-smoking at home, with his treasure trove of art—about half a billion dollars’ worth—and the latest in a long line of identical French bulldogs named Moujik.

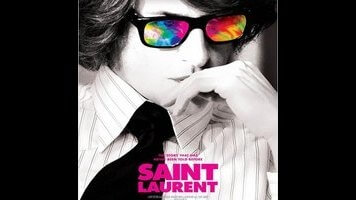

Saint Laurent, Bertrand Bonello’s anti-biopic on the fashion icon, is overlong and opaque, even boring in spots, but it contains long passages of real poetry. Given the conventional biopic treatment in last year’s colorless Yves Saint Laurent, the designer (Gaspard Ulliel) is here painted as a cubist figure, all refracted angles. This is Yves Saint Laurent seen through his habits, collections, and addictions—sketching at a trestle desk, always on narrow slips of paper, always with a cigarette, usually in a white smock, sometimes with a Moujik at his feet. Deglamorized, decontextualized, and—in one ingenious split-screen sequence—cut off from the politics and cultural upheaval of his time, he somehow becomes more credible as an artist.

With two-and-a-half hours at his disposal, Bonello—an eccentric, unconventional, often sensual filmmaker—recreates the texture of life and work in the world of mid-20th century high fashion, without ever mentioning the most over-mythologized aspects of Saint Laurent’s life: his abrupt rise to fame at Christian Dior and his rivalry with Karl Lagerfeld. Instead, Saint Laurent focuses on two incidents from the mid-1970s: the designer’s affair with Jacques De Bascher (Louis Garrel) in 1974, and the unveiling of his fall-winter “Russian” collection in 1976. (De Bascher was Lagerfeld’s long-term partner, which makes his effective exclusion from the narrative—seen in two shots, and mentioned only once, simply as “Karl”—seem even more like a radical attempt at cutting out the bullshit in order to home in on a theme.)

“Focuses” is used loosely here, because De Bascher isn’t introduced until 50 minutes into the movie, in a wordless nightclub sequence that’s a marvel of composition and construction, and the Russian show goes unmentioned until the two-hour mark. And yet the film, which hops around from the 1960s to the 2000s, seems, in retrospect, to be continually rehearsing and refracting these two key moments. Perhaps it’s the kind of thing that has to be seen twice in order to figure out how all the pieces fit together, if at all.

Bonello is a poet of night moods and all things traditionally considered nocturnal: dreams, dancing, hard drugs, semi-anonymous sex, people packed tightly into corner tables, exhausted bodies sprawled out on beds and couches. His last feature, House Of Pleasures, was a dreamy haze, squirts of perfume and wisps of opium smoke drifting through an ornate brothel parlor circa 1900. Saint Laurent, in contrast, is nightmares, cocaine snorted off compact mirrors, discos with mirrored walls, mirrored ceilings, mirrors hung in fitting rooms and dressing rooms. When Saint Laurent first sees future muse Betty Catroux (Aymeline Valade) from across a nightclub, he imagines her as himself; when they finally make eye contact, it’s in a floor-to-ceiling mirror, both dressed head-to-toe in tight black leather.

Though it’s sometimes abstract to a fault, Saint Laurent captures both the private frustration and the private sense of accomplishment that comes with making art. This is a story without valedictory applause; the triumph of the Russian collection, for instance, is communicated through splits-screens that resemble Piet Mondrian paintings, suggesting Saint Laurent’s own favorite art. If so much of Saint Laurent seems like a refraction of the Russian collection and of the De Bascher romance, it’s probably because they themselves are refracting the same theme: that old familiar chestnut about self-destruction in the pursuit of beauty, here made mysterious and, in moments, intoxicating.