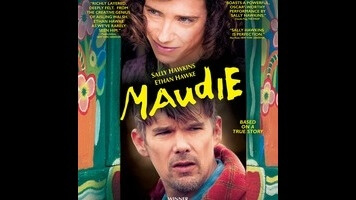

Sally Hawkins and Ethan Hawke can’t prop up the artist biopic Maudie

From her marriage until her death, the Canadian folk artist Maud Lewis lived without electricity or running water in a primitive one-room cottage in Nova Scotia, barely 10 by 12 feet, with her husband, Everett. He was an illiterate fish peddler and night watchman, described at best as a crotchety miser and at worst as an abuser who socked away his wife’s earnings and dumped her body in a pauper’s grave, only to be murdered years later for the money he’d hidden in the house. Lewis herself was a tiny woman with severely hunched shoulders, afflicted with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis that gnarled her hands into fists. She was teased out of school, cut out of her inheritance, and duped into believing that a child she had given birth to as a young woman had been stillborn. Her life in the northern boonies was deeply isolated and painful, and yet she painted the animals, boats, and farms that constituted the only world she knew into flatly colorful, cheery scenes of primitivist idyll.

This contradiction, along with the art itself, continues to draw interest to the self-taught painter, but it’s something that the biopic Maudie struggles to make into drama, even with the backing of two very good performances from Sally Hawkins and Ethan Hawke as the Lewises. Directed by British TV vet Aisling Walsh (best known for Fingersmith, a miniseries based on the same novel later adapted by Park Chan-wook as The Handmaiden), Maudie is strongest early on, as it presents the start of the relationship between Maud and Everett as the world’s sorriest production of Jane Eyre. Escaping the home of her overbearing aunt in the mid-1930s, Maud takes a job as a live-in maid to the surly Everett, cooking his meals and sleeping every night in his bed in the loft, because the only other choice is the floor. In a few weeks, they get married, because they might as well. Hawke, cast against type as an inarticulate and unsmiling hick, gives a performance that really shows his range as an actor, and though the movie doesn’t completely sand off the real Mr. Lewis’ rough edges (here, it’s a slap from Everett that leads Maud to start painting), it still sympathizes with him as a man stuck in the rules, punishments, and routines of the orphanage where he was raised.

Hawkins plays Maud as flinty and a little mischievous, a woman trying to find measures of independence and expression under extreme constraints, her only vicarious glimpses of the world beyond her tiny community coming from the fashionable American vacationer (Kari Matchett) who encourages her to sell paintings instead of postcards. Maudie is a little too smart to turn Lewis’ life into a feel-good sapfest, but once the years and decades start ticking by unacknowledged, the well-developed and subtle characterizations established by Hawkins and Hawke disappear into a cloud of aging makeup and incident: the visit from the CBC camera crew that made Lewis a minor national celebrity; the letter sent by Richard Nixon requesting one of her paintings for the White House; Maud’s declining health. The problem is as old as the biopic: Somewhere in trying to tell a life story, life gets lost.