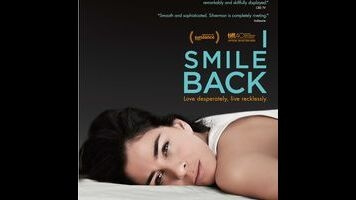

Sarah Silverman grapples with depression and a weak script in I Smile Back

How does Laney Brooks, the miserable New Jersey housewife Sarah Silverman plays in I Smile Back, know that she needs serious help? The big wakeup call arrives one wretched evening, when she chases a handful of pills with a bottle of booze, staggers into her young daughter’s room, and curls up on the floor, where she begins to feverishly grind a stray teddy bear into her crotch. Laney—face pressed firmly into the carpet, in an attempt to muffle her groans—conveys no pleasure during this sad spectacle, only shame and desperate need. She’s had rough nights before, and she’ll have rough nights after, but this is a historic low. Rock bottom doesn’t go much deeper than getting obliterated and humping a stuffed animal mere feet from your slumbering child.

That’s about as memorably grotesque as Laney’s behavior gets. But there’s plenty of self-destructiveness on display elsewhere, as our heroine sneaks off to snort coke in the bathroom during dinner or to fuck a married family friend (The Newsroom’s Thomas Sadoski) while her two children are at school. I Smile Back is a recovery drama, and though it recognizes Laney’s drug use, drinking, and infidelity as symptoms of a much larger problem—a thick fog of depression, an unhappiness she can’t shake—the film still operates in the same cyclical fashion as any story about an addict struggling to go clean, with all the inherent limitations of that genre. We gape in horror as Laney loses control, sigh with relief when she trudges off to rehab, and then apprehensively wait to see if she’ll backslide.

Silverman tackles the role with total conviction, which should come as no surprise to anyone who saw her play a similarly unhinged character in Take This Waltz—or, for that matter, anyone who’s seen her perform live. Whereas plenty of comedians offer an exaggerated version of themselves on stage, Silverman disappears entirely into an invented persona, the cheerfully, casually offensive “Sarah Silverman” of her 2005 stand-up film Jesus Is Magic. Once in character, she never breaks. Here, Silverman, who recently opened up about her own battles with depression, doesn’t just leap headlong into the bender scenes and sell the offhand despair of lines like, “I don’t see why anyone bothers loving anything.” She also offers hints of the discontent bubbling beneath even “happy” moments. There’s effort behind every grin, a touch of distraction in every instance of apparent familial bliss.

Unfortunately, I Smile Back conceives of Laney as little more than the sum of her good and bad days; she’s less a character than a bomb waiting to explode, as the tick-tick-tick of Zack Ryan’s anxious score occasionally emphasizes. The movie is based on an acclaimed novel by Amy Koppelman, who co-wrote the adaptation and specializes in stories of clinical despondency. Unable to replicate the constant internal dialogue of her book, Koppelman depends instead on Silverman and director Adam Salky to convey the intricacies of her protagonist’s frazzled thought process. But no matter how close the latter’s camera gets to the former’s face, he can’t get inside her head. Laney remains impenetrable in her misery, a cipher of domestic distress.

At best, I Smile Back offers what feels like genuine insight into the difficulties of living with crippling depression. “Everyone’s anxious their first time,” someone tells Laney as she checks herself into the clinic—a sobering acknowledgement that she’s almost expected to relapse. The importance of a strong support system is also demonstrated, mostly through its absence: As Laney’s frustrated insurance-salesman husband, Josh Charles skillfully threads the needle, showing how even the most loving partner can eventually reach wit’s end. At one point, he tells her, “I just want you to be happy, like you used to be,” which is a perfect example of the well-meaning but useless encouragement often lobbed at those with mental illness.

But where I Smile Back gets the generalities right, it falters when it comes to specifics of characterization. Is Laney a prisoner of suburbia, saddled with a wife-and-mother role she never really wanted? Do her problems stem from abandonment issues, the residual resentment she feels toward the father (Chris Sarandon) who walked out on her as a child? Flirting with pat explanations, the film settles for a vague portrait of consuming ennui, counting on audiences to be so invested in Laney’s battle with her demons—and the suspense of whether she’ll stay sober or fall off the wagon—that they’ll ignore that those demons are never really identified. What it ends up amounting to is a lot of Lost Weekend transgression, broken up by lulls of tense abstinence. And to that end, the film plays its most shocking card way too early. As Sarah Silverman the comedian could surely attest, there’s no topping a kicker like “masturbating with a teddy bear.”