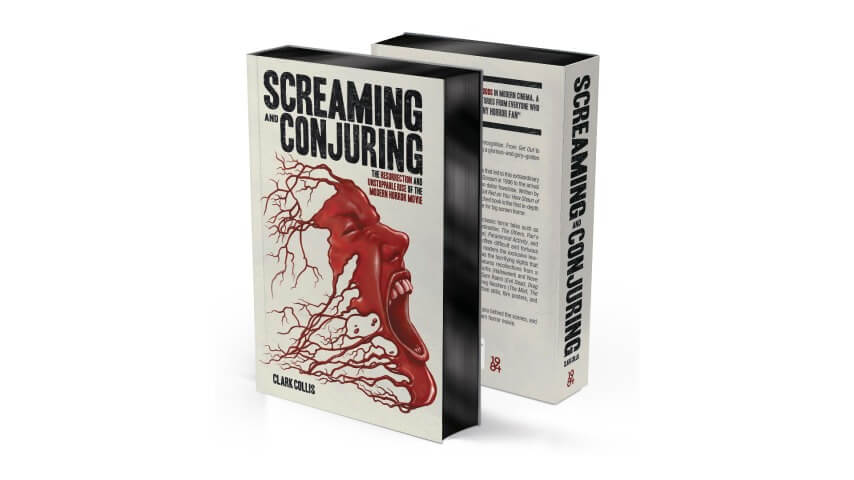

It’s never been a better time to be a horror filmmaker. The genre is experiencing a modern renaissance, with critically acclaimed horror films like Get Out, Sinners, and The Substance proving that, beyond the frights, scary movies have something to say. In his new book, Screaming And Conjuring: The Resurrection And Unstoppable Rise Of The Modern Horror Movie (on sale September 2), entertainment journalist Clark Collis examines the films that laid the groundwork for the current horror climate. Starting with Wes Craven’s 1996 classic Scream, Collis crafts a history of modern horror films, talking to key players involved with the productions and explaining how each film changed the game.

In this exclusive excerpt, Collis explores the impact of Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and its running zombies.

As Paul W. S. Anderson was shooting Resident Evil in 2001, the filmmaker’s fellow Brit Danny Boyle was overseeing his own George A. Romero-inspired zombie tale, 28 Days Later, from a script by novelist Alex Garland. The writer had become famous in his native UK following the 1996 publication of his debut novel The Beach. A thriller about backpackers attempting to find their Zen on a remote island paradise, the book was a bestseller, reprinted by publisher Viking 25 times in less than a year. Garland followed The Beach with 1998’s The Tesseract, and struck a deal to write two more books, but began to doubt if the solitary life of a novelist was for him. “I thought: Jesus Christ, I do not want to spend the next 40 years stuck in a room,” he recalled to The Guardian in 2015. “I had an advance to write two more books and I paid it back because I had an idea for a film about running zombies, which was 28 Days Later.”

Romero’s zombie films had made an impression on Garland when he was a child. “I’d seen Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead on my neighbor’s VCR when I was 13 years old, and I thought, wow!” the writer would recall to entertainment journalist Zaki Hasan. Garland’s interest in the zombie genre was reignited by the Resident Evil video games. “Probably a year or two before I wrote 28 Days, Resident Evil got released,” Garland told Hasan. “Sometimes 28 Days Later is credited with reviving the zombie genre in some respect, but actually I think it was Resident Evil that did it, because I remember playing Resident Evil, having not really encountered zombies for quite a while, and thinking: oh my God, I love zombies! I’d forgotten how much I love zombies. These are awesome!”

The writer became friendly with Danny Boyle and his producer Andrew Macdonald while visiting the Thailand set of 2000’s big-budget adaptation of The Beach, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio. The novelist later pitched Boyle and Macdonald his idea for a movie about a bicycle courier who awakes from a coma to discover that Britain has become overrun by people turned murderously violent by a virus. The infected in Garland’s screenplay were not dead, and thus technically not zombies, and sprinted where the undead traditionally shambled. Still, the script clearly owed a debt to Romero’s films and borrowed several plot points from his trilogy of Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, and Day of the Dead.

While Boyle enjoyed some horror movies, like The Exorcist and Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film Don’t Look Now, he was much less familiar with the zombie genre than Garland. So the director had no problem changing up the nature of the threat facing the film’s survivors. “No, I don’t like zombie movies very much,” the director told Amy Raphael, author of 2013’s Danny Boyle: Creating Wonder. “I find them implausible. Why do zombies just lurch around instead of running after their victims? […] I immediately said to Alex that if I was going to make the film, the zombies had to run.”

Boyle picked new faces as his leads, with Cillian Murphy playing the bicycle courier, Jim, and Naomie Harris and teenage actress Megan Burns portraying fellow survivors, Selena and Hannah. Burns was enthralled by Garland’s script, which she was given after her first audition. “I read it on the way home, on the train, and I was thinking, ‘I have to do this, it’s so good,’” she says. “It was such a visual script [that] as you read it, you could see it playing out. I have to admit that I didn’t find it very scary, but I’m into the darkness, and the goth, and the horror. But yeah, instantly I thought, ‘If I don’t get this part, I’m going to be so sad.’”

Boyle had a small budget of around $6 million but still wanted to depict a post-apocalyptic London. He resolved to shoot on digital video, hiring cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, who had worked on Thomas Vinterberg’s similarly experimental 1998 drama Festen, to help fulfil his vision. In the finished film’s most hauntingly memorable scenes, Murphy’s Jim wanders through the streets of a deserted London trying to figure out what has happened to England’s capital. Boyle filmed the sequence in July 2001, ahead of the main shoot. “We appointed our own marshals in jackets to ask drivers to stop,” the director recalled to writer Amy Raphael. “My daughter Grace, who was eighteen at the time, turned up with a few mates. They were all attractive girls. There was a heatwave, they weren’t wearing many clothes, and of course the drivers around at that time were mostly men. If I asked them to stop, they’d tell me to fuck off; a beautiful girl leaning into the car did the trick.”

The bulk of the film’s shoot began at the start of September. Boyle was still in production when the 9/11 attack occurred in New York. “I think the reason [the film] had the impact that it did is that it was the first one out of the block that touched, not directly but aesthetically and morally, some of the residue of what 9/11 had done to us,” he told the outlet Inverse in 2023. “And, in our particular case, it made cities, which feel so immense, suddenly they were utterly vulnerable.” At one point, Murphy’s Jim pauses in front of a wall on which people have left notes in an attempt to find lost friends and family members. When the film was released, this sight would seem like an eerie reminder of what had happened in New York following 9/11.

The actors who played the infected were recruited from an agency which specialized in finding work for former professional athletes. “We wanted people that could really move,” says producer Macdonald. Megan Burns recalls happily hanging out with the cast members playing the movie’s lethal virus victims. “People always say to me, ‘Wasn’t it so scary on set?’” she explains. “It’s like, not really, because you’re sat in the makeup chair next to the zombies—the infected—and you’re eating dinner with them, so there’s not that fear of people who are so lovely. It’s a film, isn’t it? It’s all play-acting.”

For the movie’s ending, Boyle originally filmed a sequence in which Jim dies after being shot, leaving Selena and Hannah as the last non-infected survivors. After that conclusion tested badly, the director replaced it with a finale where all three lived. Burns remembers preferring the original ending. “I quite liked the idea that it was me and Naomie versus the world,” she says. “I thought that was an interesting take on the final girl in horror films. It’s like these two girls are left to fend for themselves—still in the bloody ballgowns.”

28 Days Later was a hit in the UK, earning $9 million after it opened in November 2002. The movie subsequently proved successful in the US, too, where it debuted in theaters the following June. Following the initial release, distributors Fox Searchlight put out a new version of the movie that included the alternate, and more downbeat, ending. Boyle’s film wound up earning $45 million at the domestic box office.

Many reviewers embraced 28 Days Later and the film’s echoes of a reality made more uncertain not just by 9/11 but by a 2003 outbreak of the coronavirus-caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) that caused more than 700 deaths worldwide. In his assessment for The Boston Globe, Ty Burr described the film as “terrifying on the basic heebie-jeebie level, respectful toward its B-movie forebears, and all the more unnerving for coming out in this fretful era of SARS and germ warfare.”

The teenage Megan Burns received surprising proof that 28 Days Later had made a serious impact on the culture when she sat her A-level exams a couple of years after shooting the movie. “I did film studies, and one of the questions was about how the marketing of 28 Days Later led to its success,” she says. “I remember loads of people in the exam room giving me a look like, ‘You’ve aced this, then!’ But I still didn’t get an ‘A’ on that paper. I wasn’t involved in the marketing of it. I was just a kid, going along, enjoying the shoot.”

© 2025 by Clark Collis. Courtesy of 1984 Publishing.