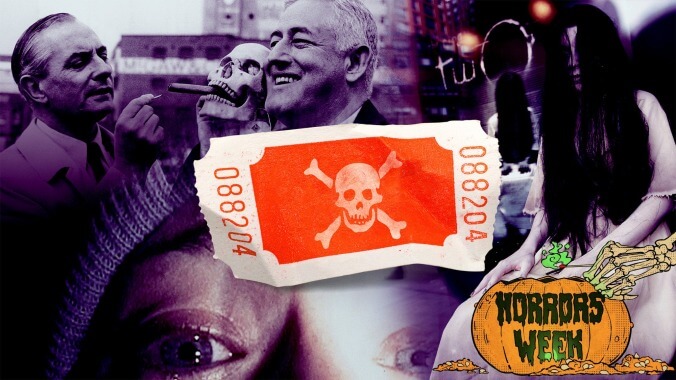

Screen at your own risk: 11 dubiously lethal movies

These scary movies don’t just promise the rush of a good scare—they claim to depict events so perilous, they’re a genuine threat to members of the audience.

Photo: John Pratt (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images), Paul Hawthorne (Getty Images), Getty Images Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Most movie marketing is about enticement: Hear Greta Garbo talk! Believe that a man can fly! Feel the unremitting, night-vision-camera terror of this Paranormal Activity audience for yourself! In horror promotions especially, there’s an undercurrent of danger to the seduction—you’re going to scream and nobody’s going to hear you, it still isn’t safe to go into the water, you’re repeating “it’s only a movie” to avoid fainting. But a select class of scary movies goes one step further. They don’t just promise the adrenaline rush of a good scare—they claim to depict events so pulse-pounding, so perilous, they’re a genuinely lethal threat to members of the audience. This type of “killer” B-movie pioneered by wily showman William Castle has its modern descendants, too, in films purporting to depict the deaths of the people in front of the camera. (Actual on-set tragedies like the ones that befell Twilight Zone: The Movie and The Crow notwithstanding.) Scoff if you must, but viewer beware: Just because the following films haven’t claimed a life doesn’t mean that yours won’t be the first.