Searching For Ingmar Bergman doesn’t uncover much fresh insight about his life and work

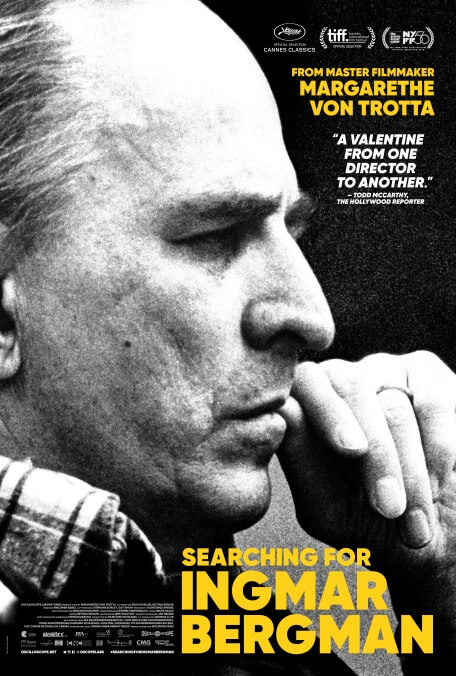

Margarethe von Trotta begins her documentary Searching For Ingmar Bergman with a personal anecdote, describing in detail her first encounter with Bergman’s work. As Max von Sydow’s chess-playing knight challenges Death to a game early in The Seventh Seal (1957), von Trotta analyzes the sequence shot by shot, then explains how seeing it changed the course of her life, inspiring her to become a filmmaker herself. Her career hasn’t been quite as momentous as his—precious few can boast of that—but movies like The Lost Honor Of Katharina Blum (1975, co-directed with her husband at the time, Volker Schlöndorff), The Second Awakening Of Christa Klages (1978), and Rosa Luxemburg (1986) established her as a formidable voice in the New German Cinema movement. As it turns out, Bergman reciprocated her ardor: When he was asked by the Göteborg Film Festival, in 1994, to name the films he loved most, he included von Trotta’s Marianne & Juliane (1981) on his list of 11 all-time favorites, alongside such better-known classics as The Passion of Joan Of Arc, Rashomon, Sunset Boulevard, La Strada, and Andrei Rublev.

Unfortunately, that’s pretty much the full extent of Searching For Ingmar Bergman’s unique personal take on its subject. Von Trotta interviews a few other filmmakers (Olivier Assayas, Carlos Saura, Ruben Östlund), who speak eloquently about Bergman’s importance to their work, but she never fully commits to making her film either heavily autobiographical or a more general consideration of artistic influence. Indeed, she doesn’t settle on any particular idea or approach. Part of the problem is simply that Bergman’s legacy is too monumental, and his oeuvre too vast (45 features over seven decades, at least a dozen of which are classics), to be tackled with any rigor in just an hour and a half. Von Trotta includes numerous clips of his work, and she talks to collaborators ranging from Liv Ullmann to his longtime script supervisor, Katinka Faragó, but none of this material has been fashioned with any apparent larger purpose in mind. Various people wander into the film at random, tell a story or two, and then leave.

Bergman was born in 1918, so it’s probably no coincidence that this documentary is appearing now, during his centenary; the film premiered in the Cannes Classics sidebar earlier this year (along with another, reportedly less hagiographic doc called Bergman: A Year In A Life), and was likely commissioned. It has the shapeless, semi-improvisatory feeling of a class assignment that was researched and assembled in a hurry. One surprisingly lengthy section focuses on From The Life Of The Marionettes (1980), a TV movie that Bergman made in West Germany while he was battling with the Swedish government about taxes. Watching this film (which barely mentions The Virgin Spring or Cries And Whispers), you’d get the impression that it’s a major Bergman film, rather than one so insignificant than even fans barely know it. (It appears to have been singled out primarily because one of its actors, Rita Russek, lives relatively near von Trotta.) Ultimately, the search here isn’t so much for Bergman as it is for a thesis and conclusion. Those who know nothing about the subject will learn a little. Those who know a lot will learn very little.