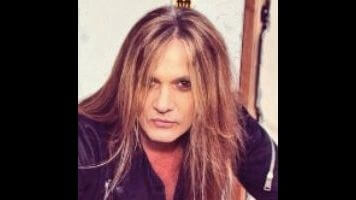

Sebastian Bach isn’t one to skimp on rock star excess. During his heyday as the frontman of the late-’80s and early-’90s metal act Skid Row, Bach was notorious even among his fellow headbangers for his hard-partying, outrageous lifestyle. Kim Thayil of Soundgarden once recounted the story of his band playing a show with Skid Row, and afterward, the lanky blond frontman appeared drunk in the middle of their dressing room, wondering why they were putting on their coats and preparing to leave. “A lot of those guys feel like it’s their job to keep the party going,” Thayil said, and that spirit informs Bach’s ribald and freewheeling memoir, a book largely untainted by self-awareness.

18 And Life On Skid Row is often a delightfully trashy and salacious read, a rock memoir that understands where the appeal of the genre lies—over-the-top behavior by rock stars ensconced in a musical cult of personality. Like Mötley Crüe’s The Dirt or David Lee Roth’s Crazy From The Heat, Bach doesn’t hold back from relaying all the dirtiest and most appalling behavior, from stories about hoovering up cocaine straight from the tray table on pre-9/11 flights to fond remembrances of group sex in hotel rooms, backstage holding areas, and other impromptu venues. These exploits are the sprawling, night-that-beggars-belief odysseys of which hair-metal legends are made: getting threatened by Jon Bon Jovi, drunkenly disrupting charity press events, doing coke with Lars Ulrich for so many hours that Bach’s grandmother has to pick him up from the Metallica drummer’s house. And it’s entertaining, although the prose is generic, sometimes comically so. (“Getting drunk and fucking is definitely one of my favorite pastimes. I highly recommend it. It’s fun.”)

The distance of time has not given Bach much objectivity about his past. Many stories end with him getting incredibly drunk and acting like an asshole, to the point that his final years with the band find him relegated to his own tour bus, the rest of his bandmates having no desire to spend time with him in close quarters. Even all these years later, he chalks the bad blood up to jealousy on their part, failing to see that his abhorrent behavior led directly to the band firing him. The book opens with an incident meant to show his humility in the face of bad judgment—he accidentally hits a woman in the audience with a bottle one night, and when he’s arrested, he feels incredibly bad about it. But even here, he doesn’t understand that maybe he also shouldn’t have leapt into the crowd and broken a man’s jaw. (That guy threw a bottle at Bach on stage, so apparently he earned it.) Instead, all the tales of debauchery, from the lascivious to the violent, end with Bach throwing up his metaphorical hands as though his life were simply out of his control. Seemingly half of the book’s recollections end with “That’s rock!” or “Rock it up!” or some other variation on that lunkheaded coda.

There is more innocent material here, too, but it’s rarely long before it veers back into ridiculous territory. He snags a starring run on Broadway in the title role of Jekyll & Hyde: The Musical, and soon there are tales of getting crazy drunk. He films a VH1 show and then gets crazy drunk. His lifelong KISS fandom leads to a recording session with guitarist Ace Frehley, and soon Bach is snorting cocaine, getting crazy drunk, and trying to drive home in a snowstorm. It’s not like he’s alone in this behavior. His fellow rock stars exhibit similar proclivities for asshattery under the influence. (Vince Neil “thinks it’s funny to punch people out”; James Hetfield’s homophobia almost drives him to attack a guy in the street, apparently for having the audacity to be gay near James Hetfield.)

The overall impression one gets of Bach is of an outgoing and genial person who can’t quite see what an excruciating drunk he could be. Not always—there are some very funny incidents where he plays a good-natured straight man to more deliberate assholes like Axl Rose or David Lee Roth. Yet Bach’s own autobiography is filled with enough examples of his dickishness that you’d hope he would have drawn some insight from them. Not that 18 And Life On Skid Row needs more introspection. It’s a messy and ramshackle memoir, bouncing from era to era and story to story with little more than a vague chronology. Still, it works because of Bach’s puppyish enthusiasm—for music, yes, but also for booze, for drugs, and for sex in unusual places. Rock it up!

Purchase 18 And Life On Skid Row

here, which helps support The A.V. Club.