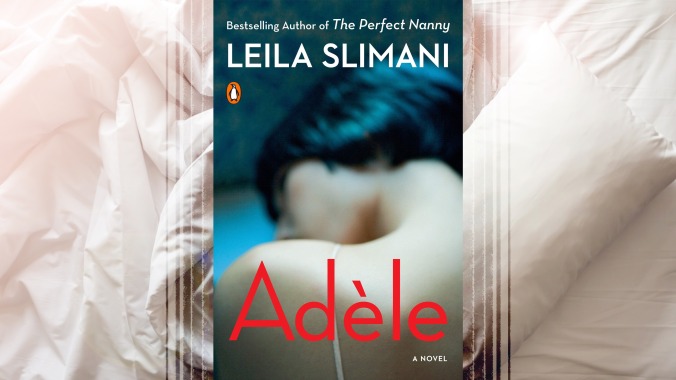

Adèle, by the French-Moroccan author Leila Slimani, is set to be released in English tomorrow, coming to English readers after Slimani’s Prix Goncourt-winning novel, The Perfect Nanny. But chronologically, Adèle came first. It was the author’s debut novel, apparently one inspired by the well-publicized scandal involving the former head of the IMF, Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

It must be said that Strauss-Kahn is a man who was accused of sexual assault by a Guinean housekeeper at a New York hotel. Criminal charges against Strauss-Kahn were ultimately dropped, and civil lawsuits settled out of court. But what does Adèle have to do with that? The novel’s namesake is a sex addict living in Paris, married to a gastroenterologist, Richard, who is blissfully unaware of his wife’s addiction despite her flimsy excuses and progressively sloppier cover-ups of her affairs. Richard’s obliviousness coupled with Adèle’s shame compels her to push the envelope further and further, to sound out the limits of her secret or, perhaps, toy with getting caught. It’s fascinating—in a curio shop kind of way—but it beggars belief that Strauss-Kahn could have had anything of it, except, perhaps, sex, though that’s, at best, a very strange way of looking at it. The novel does have a great deal of it, in fact, a dizzying array of sex scenes, intended to be rote, to satisfy an itch. It’s sex with Richard that takes the most out of Adèle. “For days on end she thinks about it as a sacrifice to which she must consent.” Being with her 3-year-old son, Lucien, is also onerous. When pregnant, Adèle “knew that something inside her was dying.” When not: “Lucien is a burden, a constraint she must get used to,” though how exactly she deals with his care isn’t entirely clear.

One can’t be prepared for Adèle. The Perfect Nanny, a devastating little book also inspired by a real-life case—that of a New York nanny who killed the two children in her care—is like the spreading of an infected wound. It’s calibrated precisely to hurt; it begins with the words “The baby is dead”—a deft surgical removal of expectations that readers may have for a novel titled “The Perfect Nanny.” (Incidentally, Slimani’s editor at Penguin intended for it to fit the mold of woman-fronted psychological thrillers like Gone Girl. A New Yorker profile of Slimani from last year quotes the editor as saying, “We’re getting this book into places like Walmart and Target,” then mentions a one-star Goodreads review by a reader who wondered if she’d read the book in the wrong order.)

Slimani is obviously not Gillian Flynn. She may have an affinity for the lurid, but her true interest is in who these women really are. And while The Perfect Nanny ends up with infanticide and Adèle with something far more ambiguous, it’s the former that manages to lay a firmer grasp on universality. Well before the book’s grisly ending, the middle-aged nanny becomes a symbol of the exhaustion of motherhood and the impossibility of do-overs, a character worthy of sympathy. The first impression Adèle gives, however, is perhaps its most effective: The English translation never uses the word “nymphomaniac,” but it’s hard not to roll it around in one’s head and wonder why it’s not considered grossly misogynistic in common parlance. It’s the sort of thing Slimani is likely to draw out from her readers by steeping them so deeply into the psyche of her seemingly depraved women. There is no great twist in Adèle, and perhaps even no ultimate judgment. What the protagonist thinks at a crucial moment is just more of the same. “She wishes the whole bar would drink body shots from her skin,” Slimani writes. “That they would spit on her, that they would reach into her guts and rip them out, until she is nothing but a shred of dead flesh.”

That intense, painful repetition is, of course, the point. But it amounts to less than Slimani may want it to. The standard that readers who loved The Perfect Nanny will hold Adèle to—both the woman and the book—is too high.

Part of the disappointment is in realizing Slimani’s shtick. All she wants is for us to sit with this person for some time—and that’s great—but in Adèle, unlike The Perfect Nanny, this yields diminishing returns. When Richard buys Adèle a brooch for Christmas, she is filled with revulsion. When she contemplates her “conquests,” she feels nothing at all. “She has no clear memories of them, and yet these men are the sole landmarks of her existence… And when, years later, she happens to bump into a man who tells her in a deep and slightly shaky voice, ‘It took me a while to get over you,’ she draws an immense satisfaction…as if, in spite of her best intentions, some sort of meaning is somehow mixed up in this eternal repetition.”

But then Adèle does have a twist coming. Late in the book—too late—Richard gains a perspective, a stake, before turning to the inevitable. For the reader with some fealty to Slimani’s way, it’s profoundly unsatisfying. But for that persnickety Goodreads reviewer, it’ll work: It delivers that pulpy quality one should never have expected from Slimani in the first place.