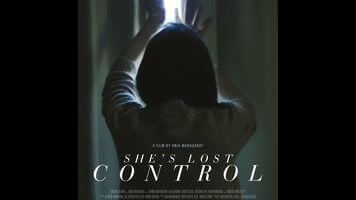

Sex surrogacy drama She’s Lost Control keeps its cards close

“Every relationship must end.” This bitter but truthful observation is made by Ronah (Brooke Bloom) midway through Anja Marquardt’s debut feature, She’s Lost Control. Though decidedly anti-Hallmark in tone, Ronah’s proclamation isn’t one of pessimism, but an attempt at forcing a realistic outlook—as if through speaking this statement, her own emotional stakes will be lessened. As a sex surrogate who works with men (all notably white and good looking, from the luxurious-haired never-nude to a nebbishly hip introvert) who have “sustained problems with intimacy,” Ronah uses such talking cures to structure her own life. But soon the woman’s grip on her interior life begins to weaken, and, to riff on Patsy Cline’s great ballad to broken hearts, she falls into enigmatic pieces.

At its simplest, She’s Lost Control is a tale of girl meets boy (where “boy” is the lead’s latest client, Johnny, played by Marc Menchaca), and at its potential worst, just another attempt to probe the line between sex and self though the figure of the sex worker. While some of these tropes remain, Marquardt leaves too much intentional ambiguity for her film to fall victim to predictability. Beginning with the protagonist speaking directly to the camera (“Yes, you pay me for my time […] but you can’t control how I feel”), Marquardt uses this unconventional open to coyly lay out her film’s themes while still, as the unsettling climax proves, playing the final hand close to her chest.

A student of behavioral psychology, Ronah is working toward her master’s with a therapist who refers clients to her. Intercutting between Ronah’s client work (mostly enjoyable and sometimes challenging) with scenes of her isolated domestic life, Marquardt paints a portrait of a woman removed from the world. Intimacy, it seems, is easier preached than practiced. But while Ronah plays the part of the emotionally advanced academic (she uses catchphrases like “creating a safe space”), Bloom never represses her character’s turbulent emotional state. Rather than offer a portrait of a hysterical woman, the actress communicates with quiet, small actions—slightly pursed lips, widening her already doe-like eyes—hinting that Ronah is far more emotionally vulnerable than her discourse would lead her clients, and herself, to believe. By the conclusion, Ronah has lost control of the world she inhabits. But this breakdown isn’t the end; instead, the heroine is offered the space to examine her own life and strength. Every relationship must end, but the longest will always be with oneself.