Whoever first used the now-familiar shot where a camera is positioned at water level and observes its half-submerged subject as waves lap at the lens should be included in the special thanks of the end credits to Adrift. This true-life survival story wouldn’t be impossible to film without that shot, but director Baltasar Kormákur and cinematographer Robert Richardson use it early and often in their story of young lovers who agree to sail a rich couple’s boat from Tahiti to California and must fight for their lives when a storm knocks them off-course.

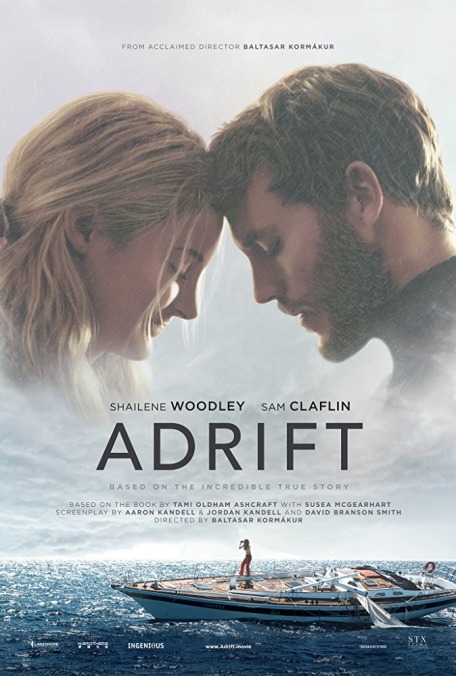

That particular water-treading camera angle may be a visual cliché, but Richardson shoots the hell out of it, as he does images of the vast, bright sky backlighting his stars as they sail across the Pacific. There’s also a grabby opening where the camera pans up from an underwater shot into the flooded interior of a boat as Tami (Shailene Woodley) regains consciousness and stumbles around the cabin in an unbroken (or cleverly fudged) take. As Tami finds her bearings and figures out how to rescue her fiancé, Richard (Sam Claflin), who she spies clinging to a lifeboat some distance from the ship, the movie cuts back to the couple’s meeting, their bond over mutual wanderlust, and Tami’s free admission, chilling in retrospect, that Richard is the “real” sailor in the relationship, while she is more of an amateur. Back on the boat, the big sailing tasks nonetheless fall to her as Richard’s broken leg and ribs prevent him from even sitting up, in another role of physical limitation for Claflin following Me Before You. (You can say this for the erstwhile Finnick Odair: He doesn’t have a problem ceding the screen to his female co-stars.)

Although Woodley and Claflin are the only people on screen for many scenes, and only a handful of other characters have more than a couple of lines, this isn’t necessarily an actor’s showcase. Woodley has to contend with some awkward talking-to-herself scenes (better handled, it must be said, by Blake Lively in The Shallows), and Claflin spends a lot of time on his back, suffering handsomely. In their pre-storm scenes together, the courtship of Tami and Richard stays puppy-ish and hippie-dippie vague: “I’ve never met anyone like you,” she says to him. Even by movie-romance standards, there’s nothing especially relatable about their few stumbling blocks, like Tami initially balking at the sailing trip because it will put them in San Diego, the site of her unconventional and unhappy upbringing. (Richard, ever the gentleman, patiently refuses to bring up the fact that they can immediately fly out of San Diego, with first-class tickets no less.)

Given the sweetly dull-witted relationship at its center, Adrift threatens to bog itself down with the endless intercutting back and forth in time. But the movie has a little more up its sleeves, narratively speaking, than first appears, and Kormákur converges the two timelines effectively. Although the Icelandic filmmaker’s earlier American films include a pair of flashy, pulpy Mark Wahlberg vehicles, Adrift is closer to his terrors-of-nature procedural Everest, and by virtue of having far fewer characters, feels correspondingly less fixated on the gruesome deaths the natural world can dole out to adventurous souls.

It’s hard to say whether Adrift would be even more effective if the characters at its center had more to them than the good luck of being embodied by likable, empathetic actors. In some ways, the physicality of the sea (vast, looming) and even the boat (creaky, and more fragile than it initially appears) are ultimately more important to the story’s effectiveness than a romance for the ages. Kormákur and Richardson haven’t made a survival story for the ages, but they do make a case, however briefly, for the value of old-fashioned visual spectacle that’s unafraid to work on a smaller, simpler scale than its disaster-movie cousins.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.