Sharon Jones deserves a better biography than the soulless Long Slow Train

“What is soul?” George Clinton asks in the song of the same name, the final track on Funkadelic’s eponymous 1970 debut album. “I don’t know,” his bandmates shout-answer through plumes of extraterrestrial pot smoke. “Soul,” Clinton responds, “is a ham hock in your cornflakes.” “Soul,” he adds in the next verse, “is the ring around your bathtub.” Then: “Soul is a joint rolled in toilet paper.” And so forth, one definition following another, until history’s foremost funksters have built a Webster’s-worthy compendium that culminates with a shout-out to an anonymous soul queen: “Soul is you / Soul is you, baby / Soul is you, big mama.” Clinton’s lyrical “you” might have been his mother, a lover, or any number of African-American women who embody the struggle that is the soulful and soul-filled life—women like Sharon Jones.

Born in 1956, the future soul/funk singer came from Augusta, the same patch of Georgia soil that nurtured James Brown. Fleeing an abusive husband, Jones’ mother moved her six children to Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, where the family sought salvation in the Universal Church Of God, and young Sharon found music. As a girl, she struggled to contain her joy while the gospel choir and band performed during services. At home, Jones and her siblings imitated Brown’s raspy croon, octave-climbing yelps, and lascivious dance steps.

Jones became a performer, singing in and out of church, embracing the sacred and the secular. She toured regionally as a backup singer for an R&B girl group called The Magic Touch, and, in 1978, cut her first recordings, a pair of funky gospel tunes with E.L. Fields And The Gospel Wonders. Her follow-up studio work wouldn’t appear for another two decades. Despite her outsize talent and ceaseless commitment to stardom, Jones, it seemed, was born 20 years too late. At least one record producer dismissed her as “too short, too fat, too black, and too old.” She’d eventually find success at the age of 46, when the Daptone Records label released Dap-Dippin’ With Sharon Jones And The Dap-Kings in 2002. Seven bestselling albums, multiple world tours, and a Grammy nomination followed.

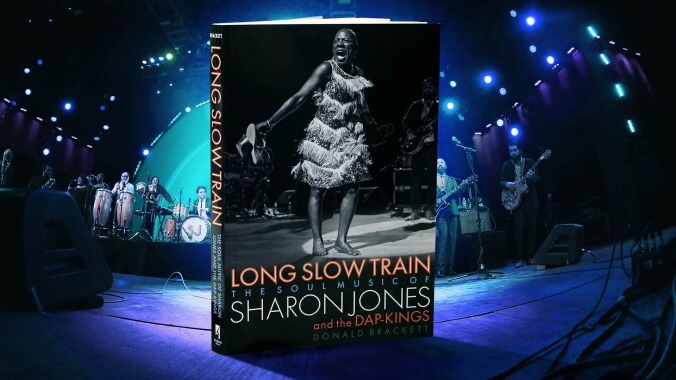

Sharon Jones deserves a great biography, maybe even a feel-good biopic along the lines of Barbara Kopple’s 2015 documentary, Miss Sharon Jones!, which traces the singer’s battle with pancreatic cancer (Jones would die the following year at the age of 60). Regrettably, Donald Brackett’s Long Slow Train, is not the tribute Jones or her fans deserve. The author of books on Amy Winehouse and Fleetwood Mac, Brackett introduces his latest subject by acknowledging the two-year anniversary of Jones’ passing. “My, my,” he writes, “how time flies when you’re dead.”

It gets worse. Much worse. The first chapter provides a chronology of Jones’ life and career much like a fifth-grade historical biography (“1965: Sharon puts on her first public performance, as the angel in the Christmas pageant at the North Augusta Baptist Church.”). The next three chapters—each longer, slower, and more repetitious than the one prior—read as if Brackett couldn’t decide whether he wanted to write a book about Jones or a half-baked slog through the history of and theory behind soul music (the author ranks Jones as “not just the equal of Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, and Tina Turner, but in many respects their superior,” without following up on the how or why). There’s little to recommend among the Wikipedia-entry-styled chapters on Jones’ bandmates, albums, standout concerts, and music videos, or the numerous instances, 10 by my count, of the author calling her music “raunchy.”

Brackett does not interview a single Dap-King. He includes little on the band’s Grammy-winning work with Winehouse, and nothing on Jones’ collaborations with Lou Reed, David Byrne, Rufus Wainwright, and Phish, nor her standout appearance in Denzel Washington’s The Great Debaters. He glosses over Jones’ decades defined by struggle: day-jobbing as a corrections officer while moonlighting as a wedding singer. Simply put, this book lacks soul.