Shasta McNasty was every bit as bad as its title

Image: Graphic: Karl Gustafson

If Shasta McNasty is memorable for anything other than having the worst title in the history of television, it’s that it headlined an era of sitcoms so bad that it forced the Baltimore Sun to ponder the format’s mortality, to despair at the thought of something called Shasta McNasty being “an end in itself.” This assessment was overwrought—the 1999-2000 season gave us Freaks And Geeks, Mission Hill, and Clerks: The Animated Series, as well as Malcolm In The Middle—but not overly so. This was also the season of forgotten curios like The Mike O’Malley Show, Battery Park, Sammy, Talk To Me, Then Came You, God, The Devil And Bob, and Work With Me, all of which were yanked by their respective networks after only a handful of episodes.

Shasta McNasty, on the other hand, was allowed by UPN to air its 22 episodes, despite having been hammered the hardest. Critics throughout the country, monocles mid-shatter, gnashed their teeth at the comedy: “Outlandishly bad,” “depressing,” “aggressively stupid and offensive.” The San Francisco Examiner likened it to “being punched really hard in the nose but not falling down,” while the New York Daily News said it was like watching a biology teacher electrocute dead frogs to stimulate their muscle contractions. One despondent critic called it a “dumbedy,” presumably before tossing their pencil in the air and shotgunning a Coors. Sitcoms rebounded, obviously, the seeds of their reinvention sprouting from the premiere of the BBC’s The Office a year later, but surely this low-stakes comedy about Venice Beach’s friskiest friends isn’t as bad as these pearl-clutching critics proclaimed.

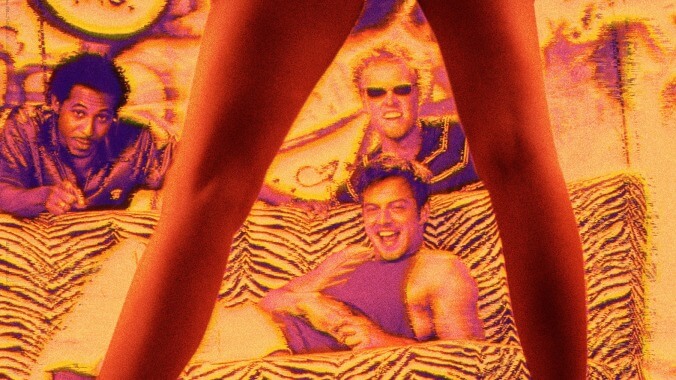

Except that, rather miraculously, it is. Shasta McNasty is, to channel our inner Maude Flanders, reprehensible, a deeply cynical reflection of the 12-34 demographic it sought to court. Created by Jeff Eastin, the series tracks a trio of bad boys—Scott (Carmine Giovinazzo), Dennis (Jake Busey), and Randy (Dale Godboldo)—with eyes for little but long legs, fake boobs, and cold beers. The pilot opens with the dudes (who make up the hip-hop group the show is named after) filming a busty neighbor without her knowledge as she strips and sleeps with her boyfriend. The follow-up finds them relentlessly harassing Verne Troyer—Dennis, deranged in his hatred, nearly froths at the mouth while mocking the actor’s height—who enters their good graces only after he acquiesces to being used as a human bowling ball. In another episode, the boys’ search for girls with “no self-respect” leads them to an “eating disorders clinic” where they tell a room of anorexic women to “eat a cheeseburger!” Shasta McNasty is essentially what It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia would look like if it idolized its characters.

We could go on, but nobody needs a catalog of the offenses of a 20-year-old UPN sitcom. Besides, Shasta McNasty is more interesting as a Poochie-like scramble, an artistic identity crisis that somehow overestimated its audience’s desire for “eXtReMe” portraits of boys bein’ boys. It’s also representative of a network that seemed to exist in a constant state of reinvention. Throughout the ’90s, UPN scored modest hits with Moesha, In The House, and Malcolm & Eddie—Black-led shows popular with Black viewers—but floundered in its repeated attempts to cultivate white audiences. Scour the network’s trash and you’ll find it overflowing with failed comedies, from the dreadfully low-rated Reunited Head Over Heels, a comedy about a “video dating agency” that, according to E!, was considered the “worst” new show of the 1997-1998 season.

It was a prime opportunity, then, when UPN became the home of WWF SmackDown! in 1999, a year of ratings dominance and utter salaciousness for Vince McMahon’s juggernaut that lands smack dab in the middle of its famed “Attitude Era.” Any given episode of WWE programming at the time saw “Stone Cold” Steve Austin chugging beers after wins, women stripping down in “bra and panties” matches, and a cigar-chomping wrestler called The Godfather offering his stable of “hoes” to opponents as a bribe. Shasta McNasty—which, now that we think about it, sounds like the name of an Attitude Era wrestler—was created as a counterpart to Smackdown!, a way to inject the franchise’s ribaldry into the network.

“It’s really a guy thing for us,” Adam Ware, UPN’s then-COO, told the New York Post. “We really felt that [males] 11 and up were underserved and there were two shows that really hit right down the middle of that pipeline—one was wrestling and the other was this show.”