Near the seven-hour mark of Claude Lanzmann’s 550-minute magnum opus Shoah (1985), widely considered the greatest cinematic document of the Jewish Holocaust, a woman credited only as a “survivor of Auschwitz” tells of her harrowing transport to the Nazi death camp. Her name is Ruth Elias, and her story constitutes the first section of Shoah: Four Sisters, the French filmmaker’s final work. Lanzmann, who died earlier this year, had over the course of his storied career repeatedly returned to material accrued in the making of his masterwork. Interviews shot in the 1970s and ’80s have been repurposed for a number of complementary (some have used the term “satellite”) features he’d made since: 1999’s A Visitor From The Living; 2001’s Sobibór, October 14, 1943, 4 PM; and 2014’s The Last Of The Unjust. Four Sisters remains firmly in that lineage. The scale and magnitude of the Holocaust is such that even a film as monumental as Shoah must still leave something out.

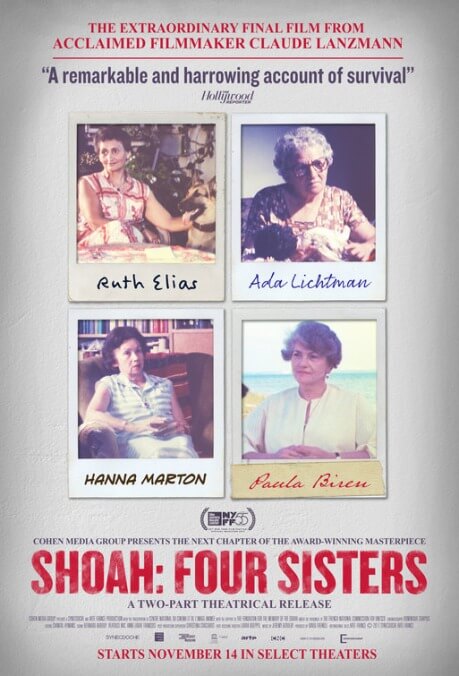

In response to criticism of that movie’s relatively minimal female presence, Lanzmann reiterated that his focus was on the mechanisms of the Nazis’ extermination process, hence the prominence of interviews with the surviving, exclusively male Sonderkommandos. (Their function within the camps was itself the basis of László Nemes’ Oscar-winning drama Son Of Saul, a film that Lanzmann admired, curiously perhaps, given his vocal opposition to cinematic representations of the Holocaust.) Made up of extensive, extant interviews with female survivors, Shoah: Four Sisters could be considered something of a corrective. Despite the title, there are no actual blood relations among the subjects; the film plays less as a holistic work than as an anthology, with each of its four parts mostly decoupled from the rest, save for Lanzmann’s recurring interlocutory presence. (Four Sisters aired on French television in four parts back in January. At New York’s Quad Cinema, where it’s included in a partial retrospective of Lanzmann’s work, the film is being presented in two viewings.)

In the first and longest part, “The Hippocratic Oath,” Elias, a Czech Jew, recalls her time in Auschwitz. After giving birth, she was forcibly restrained from feeding her newborn and then faced with the threat of the gas chamber. In a turn that gives the section its title, a sympathetic female doctor offered her a terrible choice: to either kill her baby with a needle of morphine (thus saving her own life by ensuring that she would be sent to a work detail), or doom the two of them to certain death. It’s a decision no one should have to make, but such dehumanizing impasses were precisely what the Holocaust entailed.

A series of “impossible choices” is how Lanzmann puts it to Hanna Marton in the third section (“Noah’s Ark”), which proves to be the most exemplary of that quandary. A Hungarian Jew, Marton was one of 1,684 the Nazis allowed to escape to Switzerland owing to the negotiations between Rezsö (Rudolf) Kasztner (a friend of Marton’s husband) and no less than Adolf Eichmann, a major architect of the Final Solution. It’s a troubling chapter, since Kasztner’s decision (for which he was later tried for collusion) effectively left hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews for dead in order to save a select few. Marton’s subsequent life in Israel as well as her spoken testimony here are suffused with the guilt of that knowledge.

Lacking the structural fillips of Shoah—whose overall shape is oft-unpredictable, with myriad intrusions and ruptures of its wending, troubling paths—Four Sisters relies almost exclusively on the individual force of each woman’s story. The second section, in which Ada Lichtman recounts how she was tasked to prettify stolen dolls that Nazi officers could then take home to their children, employs the occasional pan to her partner’s tear-stained face. And the last one, “Bałuty,” so named for a Polish slum district where Jews were ghettoized, includes a rare departure from the basic interview format: a brief seaside jaunt with the episode’s subject, Paula Biren (who also appears briefly in Shoah), and Lanzmann himself. But for the most part, the camera stays trained on each of the four women’s faces. Editorializing is kept to a minimum.

To offer these stories in such an unadorned manner is itself a kind of integrity, and no reasonable person could object to presenting them to a wider audience. That said, it’s fair to wonder whether the final shape Lanzmann arrives at here yields much more value than, say, the individually archived clips themselves. There’s a lingering impression that he has fashioned more of a document—a pure oral history—than anything else. But then, matters of visibility can’t entirely be discounted, and perhaps Four Sisters is best considered a parting gesture from Lanzmann, ensuring that, in his body of work at least, these four “sisters” should endure as more than just a footnote.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.