In 1969, 8-year-old Susan Nason of Foster City, California, went to bring a pair of gym shoes to a classmate who had left them at school, and never came back. A few weeks later, her body was found under a mattress in a ravine off the side of Highway 92.

Twenty years later, a man named Barry Lipsker would call the police with a shocking revelation. His wife, Eileen Franklin-Lipsker, had suddenly remembered that her father, George Franklin, had raped and murdered Susan—and that she had witnessed it. Without any other corroborating evidence, George Franklin would become the first person convicted of murder based entirely on recovered memories. That conviction was overturned after it was discovered that Franklin-Lipsker had recalled these memories while under hypnosis, which she had sworn under oath she had not. It would soon become apparent that this was not the only area where her story did not exactly line up.

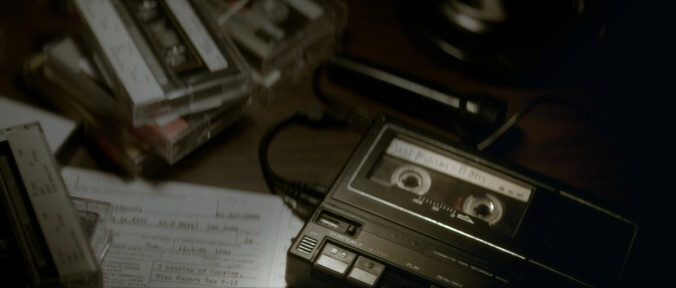

This incident sparked “the memory wars”: a fierce battle between psychologists and patients who believe in recovered memories and those who don’t. Buried, a four-part docuseries premiering October 10 on Showtime, explores the case from both sides. Directed by Yotam Guendelman and Ari Pines—the team behind the Netflix docuseries Shadow Of Truth, about the murder of 13-year-old Israeli girl Tair Rada and the man who may have been falsely convicted of that crime—Buried follows the fallout from Eileen Franklin-Lipsker’s claims through trial and media footage, as well as interviews with several people involved with the case.

The main story that Franklin-Lipsker told is highlighted in the first episode. She was looking at her daughter, who she said resembled Susan Nason, one evening when she suddenly recalled an image of her father holding a large rock over Susan’s head and bashing her skull in. It was from that flash that other memories from that day at the reservoir, where she claims her father drove her and Susan, started flooding back. Upon hearing Franklin’s memories, detectives concluded she was telling the truth; there was simply no way she could have known about those details without having witnessed it herself.

In what seems to be a purposeful move on the part of the filmmakers, even as the majority of interview subjects keep saying they believe Franklin-Lipsker and felt she was telling the truth, the inconsistencies keep piling up. Not only did experts keep stressing that this is not how our memories work, but her story was continually evolving; she and her mother both changed their story to go along with the facts as they learned them. By the time Franklin-Lipsker starts recalling other memories of witnessing her father commit other murders—murders for which another man was later convicted through DNA evidence—it becomes pretty difficult to continue giving her the benefit of the doubt.

That being said, there is little question that George Franklin was a pedophile and an abuser. While Eileen Franklin-Lipsker claimed to only remember his physical and sexual abuse later in life, her siblings had always been aware that he was abusive toward them and had acknowledged and discussed it quite frankly throughout their lives. His known proclivities are presented as one reason the jury convicted him so quickly, figuring that even if he didn’t commit this particular crime, or if he did and his daughter didn’t actually witness it, he was still a bad guy who ought to be in prison.

The docuseries’ only drawback is that it does leave out some important details, largely some that would discredit Franklin-Lipsker’s story further. A major omission is that she never said that the memory of her father was sparked by looking at her daughter until after she appeared on the Today Show and psychologist Lenore Terr, who testified on her behalf in the trial, said that a repressed memory can be brought up by a smell or a sound or “because one’s own child is the age one was at the time of the event in the first place.”

The question that keeps echoing throughout the series, both by those who believe Eileen and those who do not, is, “Why would anyone lie about this?” The conclusion reached by her supporters is that no one would, and that she is telling the truth. The conclusion reached by those who do not believe she witnessed her friend’s murder is that it is revenge against her father for having been physically and sexually abusive to her and her sisters. But there is another possibility. It could be true that Eileen Franklin-Lipsker believed that she witnessed her father murder her friend and also for that not to have happened.

Many people, mostly women, came forward in the 1980s and ’90s to say that they had recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse/Satanic ritual abuse that they had previously blocked out. Some of them not only retracted their statements later, they sued the therapists who reportedly convinced them these things happened to them. It is certainly possible that Eileen Franklin-Lipsker could have been convinced that she witnessed a brutal murder at the age of 9. There is an understandable terror, given the experience of sexual assault survivors who have not been believed, of casting doubt on the reliability of memory. There is also a huge difference between recovered memories of childhood trauma and an adult person saying they were sexually assaulted yesterday.

But overall, Buried is balanced and thorough, and not interested in injecting flashiness, à la docuseries like Tiger King. Anyone watching it who is unfamiliar with the story is going to vacillate between believing the memories were real or not, and may even come out of it not knowing what to believe—which is exactly as it should be with a case like this. It would have been easy to go at this topic from either side, with a distinct point-of-view. But because Guendelman and Pines chose not to do that, the most convincing arguments are able to stand out on their own.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)