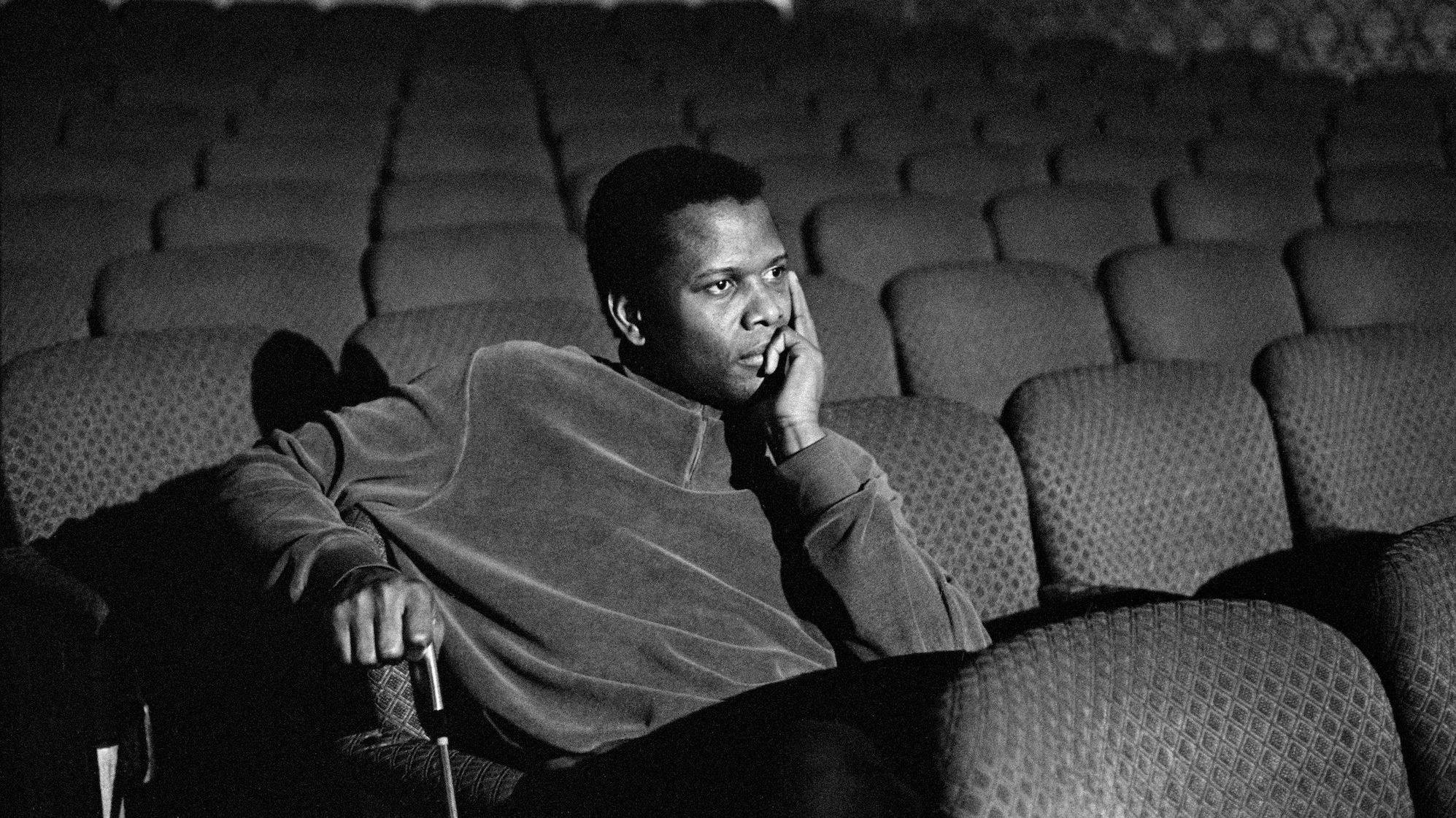

Sidney offers a portrait of Poitier's life and legacy that's only skin deep

Despite interviews with Spike Lee, Halle Berry, Morgan Freeman, and five of his children, too much of Poitier goes unexplored

Sidney Poitier, who died in January at the age of 94, forever changed Hollywood—and the world in general. Suffice to say he’s worthy of a great documentary celebrating his life and legacy as an actor and activist, but in the meantime, there’s Sidney, a good, honorable but ultimately disappointing documentary from producer Oprah Winfrey and director Reginald Hudlin that begins streaming September 23 on AppleTV+.

Hudlin delivers a standard talking-heads documentary that’s more hagiographic than revelatory, which is a shame, as Poitier surely channeled some of his bitterness over racism, aspects of his complicated love life, etc., into his indelible performances in films like Blackboard Jungle, Lilies Of The Field, The Defiant Ones, Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, A Raisin In The Sun, To Sir, With Love, In The Heat Of The Night, and so on. Instead, we get a basic overview of Poitier’s rise to fame, told chronologically, with the likes of Winfrey, Denzel Washington, Lulu, Spike Lee, Halle Berry, Morgan Freeman, Louis Gossett Jr., Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand, biographer Aram Goudsouzia, historian Nelson George, Poitier’s ex-wife Juanita Hardy, and five of his six children commenting on the doors he opened for other performers of color. Also participating is Poitier himself, filmed in glorious close-ups, his voice as strong and distinguished as ever.

Poitier opens the film, noting “I believe that my life has had more than a few wonderful, indescribable turns,” before narrating his own story. Born poor in the Bahamas, but raised by loving, proud tomato farmer parents, Poitier explains that, early on, every experience, every modern convenience, was new to him—electricity, running water, even mirrors. After a harrowing run-in with the Ku Klux Klan in Florida, he made his way to Harlem, New York, where he worked odd jobs, was thrilled to see so many people who looked like him, and met a white Jewish waiter who taught him to read. Poitier recounts how the American Negro Theatre initially rejected him, and how he met Harry Belafonte, who would over decades become his friend, competition, co-star, and occasional sparring partner. Belafonte missed a play performance to work a shift at his job, and so his understudy—Poitier—stepped in, impressed the right person, and everything changed overnight. Interestingly, Belafonte did not sit for Hudlin, who relies on comments from others and archive joint interviews (notably with Dick Cavett) to include him in the narrative.

Sidney subsequently delves into Poitier’s remarkable career. He played a doctor in No Way Out (1950) and emerged as a leading man in The Defiant Ones (1958), opposite Tony Curtis. Much time is devoted to the latter film’s ending, in which Poitier’s character tries to help Curtis’ character and falls off a train in doing so, foregoing his shot at freedom. Thus was born the so-called “Magic Negro” trope that saw Black characters sacrificing themselves to help a white man. Belafonte turned down the low-budget drama Lilies Of The Field, which won Poitier an Oscar, only the second ever awarded to a Black performer, and the first since Hattie McDaniel decades earlier. By 1967, Poitier was even more of a star thanks to To Sir, With Love, In The Heat Of The Night, and Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner.

In In The Heat Of The Night, Poitier slapped a white character who slapped him first, and it marked a seminal moment for Poitier—and for many Black men. Similarly, Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, in which a Black man kisses a white woman in the back of a taxi, proved revolutionary, particularly in the context of its time. However, Poitier found himself struck by the slings and arrows of his own people, some of whom called him an Uncle Tom, a “noble negro,” and “non-threatening” to the white establishment.

Hudlin builds a strong narrative arc, but never digs deep into Poitier’s motivations. Yes, he wanted to make his father proud and set an example for his family. Yes, he enjoyed the process of immersing himself in characters. But Hudlin glosses over key developments in his subject’s life. Poitier cheated on his first wife with Diahann Carroll, and later reconnected with her over a volatile, years-long entanglement, for example, but Hardy barely addresses it and Hudlin deploys only an old clip of Carroll very, very diplomatically discussing the relationship. Poitier and Belafonte had long approached activism in divergent ways, and a disagreement over how best to respond to Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination led to an extended rupture in their friendship. The specifics go unexplored. By 1968, Black moviegoers who wanted to see a Black man shoot a white man or romance a white girl could pony up to see Blaxploitation films at their local cinema. How hurtful was that to Poitier? Was he tempted to go there? Those questions go unasked and, as a result, unanswered.

Poitier and Belafonte reunited for the 1972 Western Buck And The Preacher, which Poitier also ended up directing a week into the shoot. Behind-the-scenes footage not only shows Poitier looking comfortable in the director’s chair, but it’s clear that he and Belafonte had mended fences, as their camaraderie is wonderful to behold. But, Hudlin again skims over subsequent events. Poitier joined Paul Newman and Barbra Streisand to form their own production company, First Artists, which was all about asserting creative control. How did it go? What happened to it? Poitier directed several popular comedies, including Uptown Saturday Night, Let’s Do It Again, A Piece Of The Action, and Stir Crazy. It’s noted that he hired Black people to work on his crews, but where are the anecdotes about working with Hollywood’s then-most-dangerous man, Richard Pryor, or the industry’s future pariah, Bill Cosby? Where’s any mention at all of Poitier’s late-career acting resurgence in Shoot To Kill and Sneakers? Beyond what’s missing, with all due respect to Winfrey, there’s way too much Oprah. Stranger still, Sidney just stops rather than ends.

In the end, Sidney is informative—it’s exciting to hear from him and from those who loved him, and from some of the people he influenced. But as evidenced by his two memoirs, This Life (1980) and Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (2000), there’s much more in Poitier’s life and legacy that this documentary fails to explore.