Silicon Valley goes big and goes home in a dark, funny, wistful series finale

Follow the sound of the pipe, follow this song

It’s a bit dangerous but I’m so sweet

I’m here to save you, I’m here to ruin you

You called me, see? I’m so sweet

Follow the sound of the pipe

I’m takin’ over you

I’m takin’ over you

– BTS, “Pied Piper”

The end of the year and end of the decade means there’s been a lot of words spilled about the best TV shows that aired during that period in recent weeks. And when The A.V. Club stepped into its role as the Great Scorer for the 2010s, Silicon Valley earned its spot on our list of the best shows of the decade at number 75. It was towards the back of the pack for HBO comedies on the list, falling behind Girls, Insecure, Enlightened, co-creator Alec Berg’s follow-up show Barry, and its former regular Sunday night partner Veep. It’s a ranking that speaks to the staggering quality of the competition, and that despite its eye for industry satire, Silicon Valley has always had more in common with HBO’s shaggier and less flashy hangout shows: Bored To Death, Flight Of The Conchords and How To Make It In America.

And that shouldn’t be taken as an insult—to borrow a commonly used phrase, it’s a feature and not a bug. As much as I’ve been frustrated over the years with the show’s tendency to spin its wheels, especially in the back half of seasons three and four, Silicon Valley has never tried to be anything other than it is, fully formed from minute one and installing upgrades since then. It’s a show about the hubris and incompetence of the tech industry, a vehicle for some of the most creatively profane jokes on television, and a showcase for a terrific comedic ensemble. If it hasn’t aimed as high as its stablemates, it’s because it never wanted to do that, comfortable in its role as class clown instead of an overachiever. And in six years, it’s scored far more hits than misses, able to pick up on the changes in a rapidly changing industry and find the humor at their expense.

With its series finale “Exit Event,” Silicon Valley gets the chance to end on its own terms and it runs with it. It’s one of the darkest and most far-reaching episodes the series has ever put together, an episode that takes the show’s oft-mocked message of “making the world a better” place and realistically introducing the idea that Richard Hendricks and company could add “by ending it” to that statement. And like any good series finale, it’s an episode that’s fully aware of its place in the series, winks and nods to the canon that lead it to a feeling of closure.

Silicon Valley began with the discovery of one little thing that had the power to change the world, with the discovery of Richard’s compression algorithm buried in an app for music copyright, and it’s fitting that it ends much the same way. With the proven success of the Son of Anton/compression hybrid at the end of RussFest, the AT&T deal is locked, and PiperNet is days from launch to hundreds of millions of consumers. Monica presents Richard with a framed image of the text he sent her confirming the deal—kudos to her for recognizing he’s one of the few people who would appreciate a blown-up photo of a text message—and he notices that there’s only three periods where he sent four. (Meant as a joke about how everything was perfect. To the last, only he and Jared think he’s funnier than he actually is.) Far from Russ Hanneman’s boast of going from three to four commas, going from four to three periods is a disaster. PiperNet is now so good at compressing data that it’s compressing text messages, which means that it’s found a way to bypass basic encryption. And having found that, it’s going to keep applying itself and learning until it moves past all encryption in its way—eradicating every boundary in its soulless quest to streamline data storage.

Jared: “Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Someone tell me how to feel.”

Gilfoyle: “Abject terror for you. Build from that.”

The idea that PiperNet itself has become the final obstacle the team needs to conquer is a perfect conflict for their final outing, for multiple reasons. It’s an ironic development that’s perfect for Silicon Valley’s twisted sense of humor, Richard’s quest to guarantee a private Internet creating something that consumes the very concept of privacy by the nature of its existence. It feeds into the rougher edged satire that’s come to dominate the show in its later years, that Big Tech’s increasing levels of disconnect from everyday life is less amusing than it is deeply unsettling. And it feeds one of Silicon Valley’s central themes, that everyone is the architect of their own destruction. Richard and his team have gone through iteration after iteration to produce this network, and what they’ve created is so good it’s the worst thing that’s ever happened. At the end of their run, they’ve failed upward to the highest peak.

Seeing nowhere to go but down from that point pushes “Exit Event” to a dark place, one that’s helped immensely by Berg taking full control as the writer and director. His recent success with the darker elements on the aforementioned Barry gives him free rein to bring that tone over here, and it works out incredibly well. The score has an almost science fiction quality to it as Gilfoyle lays out the full ramifications of what PiperNet means, shades of the cyberpunk dystopia that they’ve inadvertently had a hand in triggering. And taking place inside the empty confines of the PiperNet office, there’s an echoic quality to the staging, as you feel the weight of the consequences regardless of what choice is made. There’s no victory here, only picking the lesser of two evils.

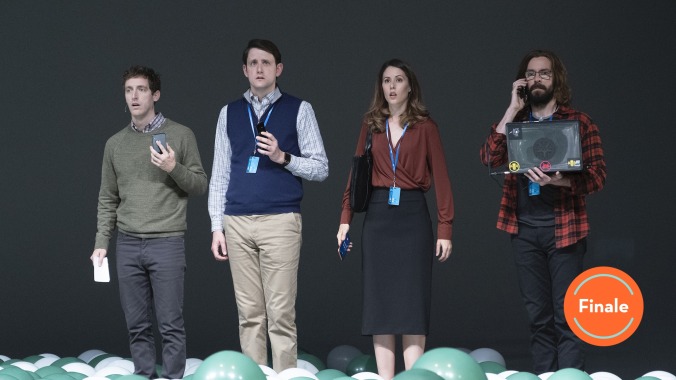

The sheer scale of the disaster gives a valid story reason to limit this final caper to the main cast, and every single one of them gets a chance to shine. Whatever gripes I’ve had about the hamster wheel plotting of the series, none of those gripes were ever directed at the main cast, which deserves to be in the conversation of the best comedic ensembles of the last decade. Martin Starr is at his deadpan best outlining the reality of what PiperNet has become, a grim monotone with just the barest hint of being proud to be right. Zach Woods is gently comforting in his uniquely horrifying way, arguably the only actor who can say “prolapsed anus” in a pep talk and have it sound convincing. Amanda Crew greets it at all with a vast range of expressions, running the gamut of fear to loathing depending on how the angle of her eyebrows. And Kumail Nanjiani continues to embrace Dinesh’s acknowledgment of his own awfulness, culminating in a powerhouse monologue where he persuades the team that his very participation in their effort to kill the network will doom those efforts:

Dinesh: “No offense to me, but I am greedy and unreliable, bordering on piece of shit. If there is a chance to stop you guys from stopping you guys, I will do it. I will sabotage your sabotage. So if this company needs to fail, like epically fail, you need to do it without me. Revoke my permissions, delete my PiperMail account. I will use Gmail like a fucking basic bitch. Don’t let me anywhere near that launch. I may beg, I will lie to you, I cannot bribe you because I do not have any money. But do not let me anywhere near that launch.”

Jared: “That is the most courageous act of cowardice I have ever seen.”

But it all belongs to Thomas Middleditch, who has absolutely made Richard Hendricks the heart and soul of this show over six years. We’ve seen Richard go through all manner of physical and mental trials as Pied Piper went from an ill-conceived app to an industry powerhouse, all of it so ably captured by Middleditch’s facial expressiveness, gift for twitchy physical comedy, and ability to switch between empathetic and asshole in the span of one minute. It’s all on display in the finale with his John Forbes Nash-style scrawlings to find the problem, the rapid cadence of his explanations, and the high pitch he takes as Gilfoyle coldly explains what needs to be done.

And yet as it all happens, there’s a sense of finality to it, that we know where this is going because we know Richard. The open question of the show has long been how much of Richard’s soul he’d sell to achieve his goals, as he’s broken bad on multiple occasions and only barely pulled back from the brink. There could ostensibly be some uncertainty if he’d be willing to go this far with his dream this close, but the frantic set to his shoulders and his cursing at Gilfoyle has the feel of a decision already made, even before he looks over the billboard and screams a Gavin Belson-style “Fuck!” to the ether. He isn’t the sort of man who’ll burn it all down for profit, and he knows it. The moment when he looks out over the crowd at the launch event and promises that the dream of their Internet will soon be over is heartbreaking to witness, exposing Silicon Valley in the end as a tragic comedy obscured by a nonstop flow of dick jokes.

Also obscuring the tragedy of it is the efforts to bring it all down, as they lay a plan in motion to crash the network and do so in a way the company can never recover. That inverse caper energy falls mostly on Dinesh, and Nanjiani does great work as Dinesh ties himself in knots, first proving there’s no way he can sabotage the event and then in a position where he has to be the third wrong to make a right thanks to John and Gabe inadvertently correcting the first sabotage. (Fucking Gabe.) The ensuing game of telephone is yet another instance of the whole team at peak operating capacity, double-checking and cursing each other out in a race against time.

And in the end, what ends them isn’t Richard or Gilfoyle’s brilliance, Dinesh’s self-interest, or even a basic failure of technology: it’s the same thing that’s brought down human empires for centuries. Trying to jam the signals created a high-pitched tone that isn’t audible to humans or dogs, but it is audible to rats. This is arguably the most delicious bit of ironic justice ever deployed on a show that has never had any shortage of that, a brilliant twist on the company name that has persisted despite no one besides Richard particularly caring for it. In a world that’s gone as high-tech as this one, only something this low-tech can bring it all back down to earth. The team is left in a poignant moment that could be the grace note of any other show, cracking multiple bottles of tequila and watching their dreams be stripped away as fast as a billboard can come down, the only people who can know how close they came to destroying and saving the world.

And ere three shrill notes the pipe uttered,

You heard as if an army muttered;

And the muttering grew to a grumbling;

And the grumbling grew to a mighty rumbling;

And out of the houses the rats came tumbling.

– Robert Browning, “The Pied Piper of Hamlin”

Except that’s not the last moment we see of this team, a development foreshadowed by the cold open format. Much like Veep allowed itself a flash-forward epilogue, Silicon Valley gives the viewers a look at the future thanks to the framing device of a Pied Piper documentary ten years after the fact. With the application of old-age makeup and The Office-style camerawork, we get a chance to see what path the Pied Piper team took when there was no Pied Piper left to conquer. Richard made his way to Stanford thanks to university president Big Head—failing upward to the last—and became a professor of ethics in technology. Gilfoyle and Dinesh co-founded a web security firm in San Francisco, Monica joined a Washington D.C. think tank that may or may not be the NSA, and Jared went to work at a nursing home where he can see the bright side of a recent herpes outbreak.

As a framing device, it’s a smart move to put the action of the finale in retrospect, as opposed to leaving questions open for debate. You get to see outside reactions of people who weren’t involved with the event, going from the insular bunker approach of the sabotage to the broader confusion and mockery that the failure left on the industry. Mike Judge’s deep roots in entertainment allow for some fun cameos, as Conan O’Brien riffs on the PiperNet collapse in an opening monologue and Mad Money’s Jim Cramer can’t tell viewers to get rid of the stock fast enough. And the show’s connection to the industry it’s long lambasted pays off with a fantastic surprise as they manage to land Microsoft founder Bill Gates—an outspoken fan of the show—as the one participant who suspects the official version of Pied Piper’s fall isn’t the full story.

The jump-forward also gives the audience a proper sense of closure for the Pied Piper team. Despite its cynicism about the industry and constant delivery of obstacles, Silicon Valley has always had a soft spot for its misfit toy box of main characters, and it leaves them in a spot that feels right for each of them individually. Jared gets to channel his need to care for others into a bottomless well of people to care for. Monica puts a continent between her and the industry whose participants she’s always not-so-secretly hated, and enters an industry that doesn’t care if she smokes. Dinesh and Gilfoyle remain shackled together their whole lives as antagonistic soulmates, sniping at each other from a desk that may as well have boundary tape on it, and manage to get rich in the process. And Richard’s free of the vomit-inducing roller coaster of being a CEO, able to educate others about the merits of tech, an area that it’s worth remembering he had some surprising natural talent. And having to append “Gavin Belson” to his title is the sort of appropriate low-key humiliation that Richard would learn to live with.

It also allows for a final beat to remember how far things have come since the beginning, as they return to the former site of the Hacker Hostel—somehow still not torn down for construction despite astronomical land prices in the Valley, but now a quaint domestic home. They recall the areas they destroyed, play a game of Hoberman Switch Pitch, and get to hear a pitch from a college-aged current resident. When they try to cite themselves as a cautionary tale, she doesn’t even know what they’re taking about (“Was that like a social media company?”), proving the memories of the tech industry are are short for both failure and success. All that’s left is the story and the connections for those who were there—and also one flash drive that Richard couldn’t keep himself from saving. It’s an ideal dark coda to close on, that the monster they created has just been sleeping, and may be ready to emerge now into a world that’s forgotten its danger. (And a possible seed for a reunion movie, given HBO’s history.)

“You don’t feel bad you never got to make the world a better place?” the documentary filmmaker asks Richard right before that beat. “I think we did okay,” Richard responds with a wistful yet contented grin. And the same can be said of Silicon Valley as a whole. You can make your arguments about whether or not it deserved to be higher or lower on our list of the last decade’s best shows, but there’s no argument that it belongs on that list. It’s a safe bet that as we close the 2010s and head into a new decade, the world of technology isn’t gong to get any less greedy, insular, short-sighted, absurd, or just plain fucked up. And while it feels like the time is right for the show to go, there’s no question that the industry will be a little less funny without Silicon Valley to take it to task.

Episode grade: A

Season grade: A-

Series grade: B+

Stray observations:

- So, let’s talk about that Erlich fake-out. When I received the finale screener with a note to embargo any mention of specific cameos, there was a part of me that worried they would bring back T.J. Miller for even one scene, possibly shot without the rest of the cast, a la Chevy Chase’s last appearance on Community. Instead, we learn that Jian-Yang stole Erlich’s identity (and possibly killed him for his share of Pied Piper’s profits) and is living in a remote Southeast Asian locale. And it’s the most relieved I’ve ever been to see Jian-Yang. I’m sure there are a cross-section of Silicon Valley fans who feel the show suffered for Miller’s departure, but I for one am glad that Judge and Berg resisted the impulse, and if he had appeared I’d have docked the episode at least a full letter grade. The show moved definitively past Erlich in its last two seasons, and Miller’s done nothing in the interim to move past his reputation as accused rapist and colossal asshole (sorry, “benevolent benign maniac”). Silicon Valley didn’t need him to come back, and he didn’t deserve the opportunity, so kudos to all involved for recognizing that.

- On the opposite note, nice to see Peter Gregory get a shoutout in Richard’s launch presentation. It’s sad we’ll never know what would have been had Christopher Evan Welch not tragically passed away during the first season, but we’ll always have Burger King. “Their selection consists of burgers, of which they are ostensibly king.”

- Gavin’s fate is arguably the funniest reveal of the flash-forwards. Rather than being sued by Rod Morgenstern for plagiarism, the two formed a writing partnership, and went on to become the co-authors of 37 hit romance novels such as Fondly Margeaux, The Lighthouse Dancer, The Prince of Puget Sound, His Hazel Glance. The old married couple bickering between the two proves that regardless of industry, Gavin will never change, and we love/hate him for it.

- Other fates revealed by the flash forwards: Laurie is in prison for an undisclosed crime and has lost most of her already limited abilities to understand human communication. Russ managed to make back the money he lost on Pied Piper by investing in hair transplants—and from the looks of that hairpiece, probably gained a comma on his own personal investment.

- A little bit of a surprise not to see Andy Daly’s terrible doctor return at some point for the final season, but the character does exist in another incarnation in the latest season of Big Mouth.

- The reveal that subterranean data center dweller John now works with Gilfoyle at Newell Roads was one of the sweeter beats of the flash-forward. I like to imagine there’s a chess board in Gilfoyle’s office and they’ve spent the better part of a decade sparring on it.

- I’ve been dismissive of Big Head as a character, but credit where it’s due: the moment where the interviewer explains his nickname is because of his last name is a wonderful bit of silent comedy from Josh Brener.

- “There was a little meniscus in the shit, and that’s where our dreams lived.”

- “I had a foster mother who thought I was the devil and that she had to kill me. And I think it was pretty traumatizing for her.”

- “The balloons are falling. Is that a good sign or a bad sign?”

- “Are you kidding me? We failed at failing?!”

- “The streets of Seattle became the streets of Sea-rattle! And everyone was sleepless.”

- “Things are better when I say them.”

- “These guys were as sweet and sound as rotting fruit.”

- “If it isn’t here… where is it?”

- And with that, our coverage of Silicon Valley shuts down. It’s been an honor and a pleasure to see this show from beginning to end. Thank you to everyone for reading over the years, and thank you to Mike Judge and company for creating a show that I’ve had more opportunity to praise than bury. In the absence of one for the finale, let’s go all the way back to the beginning for one last closing track: “Minority,” Green Day.