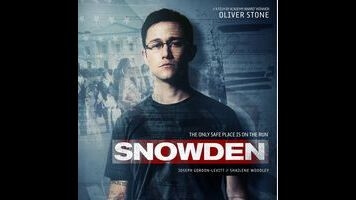

Part of the problem is that Stone, who wrote the screenplay with Kieran Fitzgerald (based on two nonfiction books), wants to depict the gradual evolution of Snowden’s conscience, which entails observing his largely uneventful life over nearly a decade. There’s nothing very compelling about watching young Ed (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) struggle through Special Forces training, for example, even if the post-9/11 patriotism that inspired him to enlist does complicate his later actions. Nor will many viewers become heavily invested in Snowden’s long-term relationship with girlfriend Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley), despite some cutesy antagonism stemming from her proto-Bernie liberalism clashing with his more conservative views. So desperate is the film for contextual background that Nicolas Cage shows up to provide a lesson on the history of encryption and its roots in early computers. When even Cage can’t elevate your movie’s pulse, it’s in danger of flatlining.

Gordon-Levitt, for his part, can’t make Snowden interesting, but he does somehow succeed in making him arrestingly uninteresting. Dropping his voice about half an octave and speaking in a clipped monotone, the actor doesn’t mimic the real Snowden so much as perform our collective perception of Snowden, a feat that’s arguably both trickier and more valuable (especially since we already have the real Snowden at length in Citizenfour). He’s a one-dimensional character, but that flatness becomes increasingly, almost paradoxically effective as the movie proceeds (in fits and starts; most of it’s told in flashback) toward Hong Kong and the clandestine meeting with Glenn Greenwald (Zachary Quinto) and Poitras (Melissa Leo). There’s no sense of a man with a score to settle, nor of an ideological fanatic holding the U.S. intelligence community to an impossible standard. Gordon-Levitt embodies the soul of a disillusioned pragmatist, which seems entirely accurate.

That’s not enough for Stone, of course. Never one to shy away from letting his own sympathies be known, he helpfully ends Snowden with footage of the real Edward Snowden getting a standing ovation from a lecture audience, just in case we fail to recognize true American heroism when we see it. Back when Stone’s films were obsessive-compulsive crescendo machines, that sort of blatant cheerleading was easier to accept, or at least stomach. Here, after more than two hours of impassive fretting, the victory lap feels unearned. One of the details from Citizenfour that Stone borrows has Snowden cover his entire body with a blanket every time he uses his laptop, to ensure that no unknown camera can pick up his password from the movement of his fingers on the keys. Snowden is like an entire movie made beneath that blanket. It inadvertently deadens material that—as we’ve already seen—should thrum with nervous energy.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.