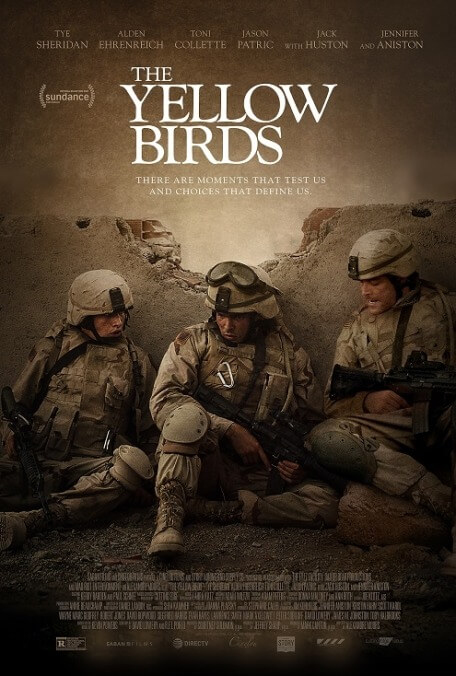

Guileless charisma is the main weapon in Alden Ehrenreich’s holster. It’s why he was perfect as the blissfully ignorant singing cowboy of Hail, Caesar!, but also, perhaps, why he couldn’t quite disappear into Han Solo: There’s no hint of outlaw amorality—of anything other than boyish magnetism, really—behind his sly tiger’s grin. Ehrenreich doesn’t smile much in The Yellow Birds. Cast as Brandon Bartle, a 20-year-old grunt shaken by what he experienced overseas, the young star extinguishes most traces of aw-shucks appeal, adopting in its place a perpetual sullenness. It isn’t the wrong approach to playing someone numbed by the horrors of the battlefield. But a single problem among many with this broody, generic anti-war drama is that Bartle never looks anything but sullen. It’s as if Ehrenreich is so intent on burying his youthful charm, on finally tapping into his dark side as an actor, that he never gives us a before to offset the after. Or maybe that’s just how the character has been (under)written.

Bartle, a private in the U.S. Army, ends up bonding with another recruit two years his junior, the polite, naïve Daniel Murphy (Ready Player One’s Tye Sheridan). It wouldn’t quite be fair to call the two of them friends or even brothers in arms, because barely any runtime is spared to develop their relationship or personalities. The plot unfolds out of order, leaping backwards and forward in time, from basic training under the hard-boiled Sergeant Sterling (Jack Huston) to the frontlines of Iraq to the home front of suburban Virginia. Directed by Alexandre Moors, who made the D.C. sniper movie Blue Caprice, The Yellow Birds might have used its nonlinear structure to confront us with how war reshapes these young men, putting who they were and who they become into conversation. But the performances don’t capture that psychological change. The film settles instead for pat dramatic irony, cutting from a scene of collateral damage to an earlier celebration at home base, images of violence replaced by families smiling for pictures, cheerful country music blaring on the soundtrack.

The source material is a very loosely autobiographical novel by Iraq War veteran Kevin Powers. But you wouldn’t necessarily guess that from watching The Yellow Birds, which seems to filter whatever genuine insights it lifts from the book through 40 years of combat-movie cliché. Visually, it’s striking but derivative: The Baghdad battle scenes are staged with the same shaky handheld “urgency” as just about every other war movie about American troops in the Middle East, and many of Under The Skin cinematographer Daniel Landin’s most handsome, memorable images—flaming palm trees, a soldier wading through murky water—are heavily reminiscent of similar shots in Full Metal Jacket. (Kubrick, of course, presented his portrait of military dehumanization chronologically, the better to emphasize the full sickening power of its cause and effect.) There’s even a touch of Terrence Malick in the somber voice-over and more “poetic” flourishes—the influence, perhaps, of unofficial Malick disciple David Lowery (A Ghost Story), who cowrote the script.

Once Bartle returns to the States, a war still raging inside of him, The Yellow Birds transforms into not just a coming-home story—another film, and perhaps there can’t be too many of them, about PTSD and life after service—but also a kind of missing-person mystery. Murphy, we quickly learn, has disappeared. His distraught mother (Jennifer Aniston), who Bartle promised before deployment that he’d look after, wants answers. So does a military officer (Jason Patric) who’s come sniffing around. “What happened over there?” asks Bartle’s own mother (Toni Collette, playing her second frazzled parent in as many weeks). The answer, concealed until the final act, is at once horrifying and almost dramatically arbitrary. If it doesn’t pack the intended wallop, it’s because The Yellow Birds, one-note in its microwaved war-is-hell nobility, doesn’t see these damaged grunts as people, exactly. They’re just abstract victims, devoid of dimension: innocents with big red targets painted over their innocence.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.