Some folks call it a Space Jail

Every day, Watch This offers staff recommendations inspired by a new movie coming out that week. This week: The Scarlett Johansson vehicle Lucy is the latest action-packed import from EuropaCorp. For the next five days, we highlight some of the French studio’s finest offerings—including a few without gunfights and car chases.

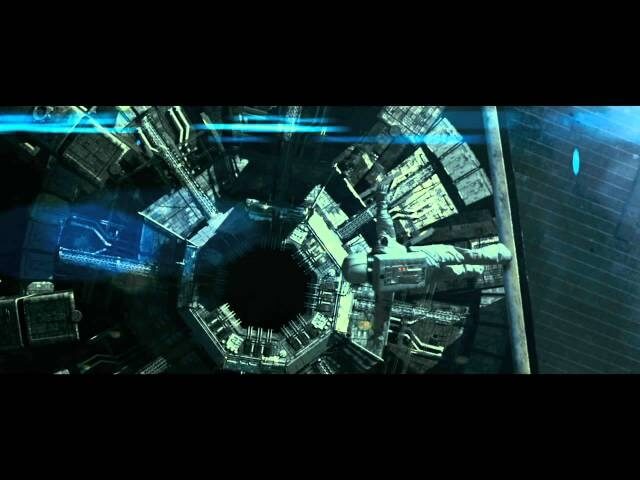

Lockout (2012)

Based on “an original idea” by Luc Besson—which presumably means that the EuropaCorp head scribbled the words prison spatiale on a paper napkin and underlined them several times—Lockout stars Guy Pearce as an ex-CIA agent who is accused of selling “space secrets” and then given the chance to win his freedom by rescuing the president’s daughter from a inmate-overrun prison that is inconveniently located in space. Flagrantly derivative, it’s something of a litmus test for the viewer’s ability to enjoy a movie purely on the basis of generic pleasures.

Though EuropaCorp has produced everything from horror movies to comedies to historical biopics, its signature genre is mid-budget action. Movies like Taken, The Transporter, or District B13 take Hollywood’s clichés—badass antiheroes, damsels in distress, scenery-chewing villains—and formulaic plots, and inject them with flashy, plastic style. The result feels equally outlandish and familiar.

Lockout’s opening sequence is a good example. Pearce’s Snow—one part John McClane, one part Snake Plissken—is being interrogated by slimy Secret Service bigwig Scott Langral (Peter Stormare, channeling Ron Silver). Snow’s dialogue consists of corny comebacks, most of which are met with a punch to the face from Langral’s assistant. (Langral: “You’re a real comedian, aren’t you, Snow?” Snow: “Well, I guess that’s why they call it the punchline.”)

The dialogue, setup, and performances are compulsively generic. (The movie’s surprisingly large fan base prefers the more appropriately Brand X title Space Jail, though it is this writer’s professional duty to point out that jails are used for detention, not incarceration.) The first part of the scene plays out as an extended close-up of Snow’s face. Every time he gets punched, he falls out of frame, revealing another one of the movie’s opening credits. Then he snaps back like a punching bag, his nose bloodier than before. Langral and his assistant are both framed out.

It’s a sharp composition—more concerned with defining on- and off-screen space than just about anything you’ll find in a Hollywood blockbuster—and it has the effect of exaggerating the scene. It nudges the derivative into the sublime, a trick that Lockout manages to pull several times over.

Availability: Lockout is available on DVD, which can be obtained from Netflix, and to rent or purchase from the major digital services.