Something That May Shock And Discredit You is more likely to charm and enlighten

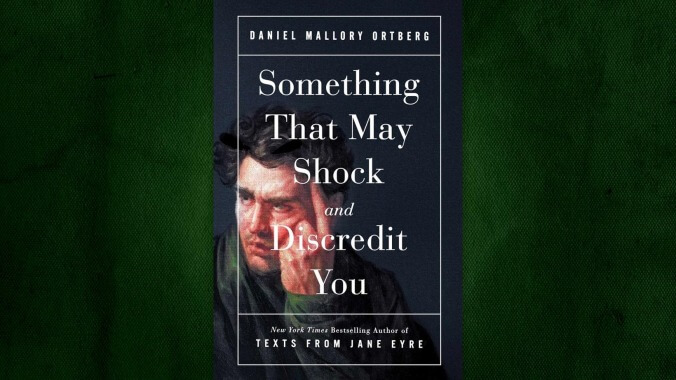

Daniel Mallory Ortberg’s Something That May Shock And Discredit You is three eloquent books in one: memoir, essay collection, and treasure trove of cultural analysis, all coming in under 250 pages. Ortberg is as nimble a storyteller as they come, so the shifts from painful personal revelations to pithy observations about Lord Byron turn on a dime while still mostly feeling part of the same whole.

Devotees of Ortberg (who, after his recent nuptials, now goes by Daniel M. Lavery), whether they were indoctrinated by his founding work at the late, great The Toast or his humorous, generous advice for Slate’s Dear Prudence column, will find a lot to love and ruminate on in the interludes and concise, biting chapters. But you don’t need to have read his previous works, Texts From Jane Eyre: And Other Conversations With Your Favorite Literary Characters and The Merry Spinster: Tales Of Everyday Horror, to appreciate the revealing first chapter, in which Ortberg touches on his evangelical upbringing and his tween-age preoccupation with the Rapture. “I never saw it coming, so I was never ready; then it was over,” he writes. It’s as much about the hour of the Son of Man as it is Ortberg coming to terms with his own gender transitioning.

The details are all Ortberg, as is the ability to turn eschatology into something more accessible and less judgmental; but the vague sense of dread that comes with puberty, spurred on by one’s growing awareness of the world, is universal. Such admissions are woven throughout the book, deployed with Ortberg’s searing wit and deep knowledge of TV, film, scripture, and Bulfinch’s Mythology. There’s no real chronology, as Something That May Shock And Discredit You moves from the author’s childhood memories to a conversation with his mother about transitioning that invokes the story of Jacob and Esau. Jacob factors heavily into Ortberg’s growing understanding and acceptance of his transition, the Biblical figure’s struggle with an angel, renaming, and new life symbolizing moments in Ortberg’s own journey to coming out as a trans man.

It’s not always immediately obvious how each chapter and interlude fits into the overarching narrative of change and acceptance, but neither is there an errant thought or word. Beginning with its title, the chapter “Apollo And Hyacinthus Die Playing Ultimate Frisbee, And I Died Watching Teenage Boys Play Video Games” exemplifies the occasionally circuitous but always insightful storytelling. Like the passages on Jacob, Ortberg casts the myth of ill-fated ancient Greek lovers Apollo and Hyacinthus through his own prism, reimagining the story as a tragicomedy while also revealing an early, unexpected insight into gender dynamics. Something That May Shock has several of these stop-you-in-your-tracks, dog-ear-that-page-now moments. The aching “The Golden Girls And The Mountains In The Sea” and its dissection of routines masquerading as intentions perfectly captures the wide-ranging fear of change and overcoming it: “The source of safety, then, cannot come from a certainty that dangers will pass and one will be permitted to resume the previous course of one’s life.” The unknown isn’t known, until it is.

Ortberg’s singular talent for combining candor with humor and erudition helps make even the most ineffable moments of his transition relatable, but he also gently cautions against a certain type of heedless empathy. In “Unwanted Coming-Out Disorder,” Ortberg declines to conflate his coming-out story with those of trans kids; it’s not just that he sees the need for nuance, but he’s also a little (playfully) miffed at having his thunder stolen. He later points to the limits created by an abundance of empathy:

The trouble only begins when it triggers an empathy-overload feedback loop and you start to imagine that it’s about to happen to you, that any minute now someone is going to travel back to your own adolescence, seize upon the mildest of gender-nonconforming behaviors… and drag you kicking and screaming into a forced-transition factory.

The desire to understand is commendable, Ortberg writes, but in the rush to acknowledge its significance and communicate their own feelings, well-meaning cis people often use the language of death and grieving and inadvertently undercut what is, for Ortberg and others, a new beginning.

Ortberg maintains a warm, perceptive tone throughout, even in the otherwise gutting “Pirates At The Funeral: ‘It Feels Like Someone Died,’ But Someone Actually Didn’t,” wherein friends mourn him despite his irrefutable alive-ness. He shows great compassion for his loved ones, but also notes that there’s “something willfully perverse about bereavement in the face of new life.” It’s not an admonishment or even a plea, but another instance of Ortberg zeroing in on something undeniably human and previously undefinable. It shows Something That May Shock And Discredit You to be more a work of great perspicacity than one of empathy, though it is certainly compassionate. But just because we feel spoken to by this book doesn’t mean we are being spoken for; as insightful as Ortberg remains about literature and media and the human condition, he’s created a deeply personal language for a deeply personal story.