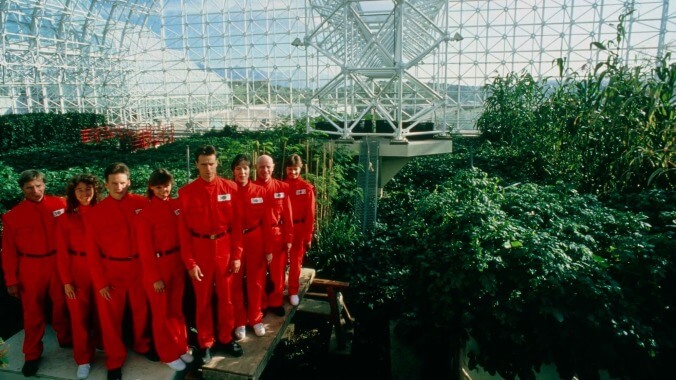

Remember when it was still outlandish, the thought of people isolating themselves from the rest of the world for the foreseeable future and the greater good? Back in 1991, what we now call Tuesday looked more like science fiction invading the nightly news. Under the glare of flashbulbs and the scrutiny of a whole planet watching from the other side of the shimmering glass, eight scientists clad in bright red jumpsuits sealed themselves inside a giant pyramidal simulation of Earth. For two long years, they’d live together in the “prefab paradise” they called Biosphere 2, hoping to determine whether we could replicate the necessary conditions of human life in an artificial, airtight environment. The experiment has faded from the public consciousness, but it was a source of much media fascination at the time—enough, perhaps, to set unreasonable expectations of “success” for its researchers.

Matt Wolf’s documentary Spaceship Earth looks back on the project with more awe and less skepticism than the journalists who cast a harsh spotlight on its compromises and controversies. That the film is arriving now, when its reflections on years spent in self-imposed isolation might resonant a little more with audiences, is a significant coincidence. Accidental timeliness aside, it’s perhaps stranger that it took this long for someone to make a movie about Biosphere 2, given both the clear dramatic shape of the story—a kind of fall from grace within a manmade Garden of Eden—and its juicier details, including the persistent rumors that the participants engaged in cultlike behavior.

Whether they were something of a cult is one of the film’s many unanswered questions. The brainchildren of the experiment were a group of ecologically minded hippies who met in the 1970s and formed a commune, Synergia Ranch, in New Mexico. They filmed everything, including their various avant-garde performances and acting exercises, which Spaceship Earth uses to fill out its overlong, over-admiring first hour. (“He simply met emotional needs,” one of the participants gushes about the group’s fearless leader and Biosphere 2’s chief inventor, John Allen. “He was a mind magician.”) Wolf’s greatest asset is the wealth of footage at his disposal, including plenty from within the vivarium itself, shot by its sometimes-restless occupants and paired with the talking-head recollections of the few that agreed to chat about the experience.

We get a passing understanding of what went wrong with the experiment: the dipping oxygen levels and food shortages, and also the violations of its closed-system principles, including a well-publicized trip to the emergency room and the use of a carbon dioxide scrubber to provide some additional oxygen—a concession that the media, perhaps, blew a little out of proportion. Spaceship Earth suggests that there was something a little intrinsically stunty about Biosphere 2’s presentation (the Star Trek uniforms were all part of its theatrical flair) that may have doomed it to bad press; every hiccup, normal for a project of this scale, was treated like a telltale sign of inevitable failure. Was there something a little snobbish, too, about some of the dismissals from the scientific community, which seemed to have less to do with credentials of the Biospherians (they had degrees and expertise) and more to do with the fact that they were New Age eccentrics operating outside of academic circles?

Those hoping for a crash course in the science of this scientific endeavor won’t find much here. Spaceship Earth mostly skims over both the findings and the failings, and neglects a lot of the logistics—understandable omissions for a two-hour documentary more interested, perhaps, in the social ramifications of those two years behind glass. Not that it totally illuminates that aspect either: Selective anecdotes paired with random vérité glimpses of the scientists result in a highly mediated remembrance. One of the interviewees emotionally cutting off a line of questioning and walking away from the camera is treated as a dramatic punctuation, but it’s simply the most explicit expression of what feels like a general reluctance to dish about the conflicts that erupted behind the scenes. Did gaining access to the footage and those who shot it come with the expectation of softball questions? Or did everyone just stonewall, unwilling to air the experiment’s dirty laundry? Either way, we get only an abstract sense of what life within Biosphere 2 was really like.

At times, the film feels like an attempt to reclaim the experiment as an act of ambitious environmentalism, not the ill-fated folly the press made it out to be. Spaceship Earth doesn’t ignore the mistakes and setbacks and stranger aspects of the group’s dynamics, exactly. But by communicating them almost entirely through snippets of news reports, it does make reasonable objections to the process seem like naysaying. Meanwhile, a constant swell of inspirational music works overtime to present the venture in terms its participants might prefer. Years after the first mission, Biosphere 2’s billionaire backer, Ed Bass, allowed the giant ecological system to fall into the hands of those who wanted only to make a profit from it—including none other than Steve Bannon, offering the film an eleventh-hour villain. But one can lament this development as a blow against further research while still wondering if we’re getting the whole story about how the experiment went down. One detractor, when asked what Biosphere 2 was if not “real” science, describes it as “trendy ecological entertainment.” That’s not so far off from what Spaceship Earth offers.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.