Another thing that was on its way out at the time was the horse-drawn carriage, still barely hanging on while surrounded by automobiles. In Speedy, the last horse-drawn streetcar route in New York City is run by the elderly “Pop” Dillon (Bert Woodruff), whose granddaughter, Jane (Ann Christy, in her only notable screen role), is Speedy’s sweetheart. When a robber baron tries to buy Pop’s line in order to create a fully motorized streetcar system—a plan that requires merging several existing routes—Pop, encouraged by Speedy, holds out for more money. For some arcane reason, however, Pop’s streetcar must run at least once every 24 hours, or he loses his rights to the route. Consequently, the robber baron makes two separate attempts to force the streetcar off the road, both of which must be heroically foiled by Speedy (who gets in some practice behind the wheel driving a motorized cab around the city).

That’s the movie’s ostensible plot, but it doesn’t really kick in until the final half-hour or so. More than most of Lloyd’s features, Speedy is a succession of tangentially related two-reelers, each of which would work would just fine on its own. Early on, Speedy is established as a man so obsessed with baseball that he insists on working “within phoning distance” (speaking of antiquated) of Yankee Stadium; a terrific series of gags finds him attempting to field orders from customers while receiving regular phone updates on the score of a game in progress, and then conveying the score to fellow employees using various food items. But the film then mostly forgets about this character trait until it’s time for Babe Ruth, then at the height of his fame, to make an extended cameo as himself, looking terrified in the back of Speedy’s cab (Speedy changes jobs on an almost daily basis) as it races through traffic, with Speedy constantly looking back over his shoulder at his hero rather than watching the road.

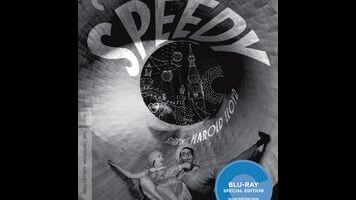

Unlike Lloyd’s most celebrated films (Safety Last!, The Freshman), Speedy doesn’t feature many death-defying stunts—its driving gags are mostly achieved via rear projection. On the other hand, Speedy does take Jane to Coney Island for an extended sequence (which was actually shot at several different amusement parks), and just about every ride they go on looks insanely, even murderously dangerous, which is presumably why most of them no longer exist. As a comedy, Speedy is second-tier Lloyd, but it remains fascinating as a visual record of New York in the late 1920s—most of Lloyd’s films (including a NYC-set short included on the Criterion disc, “Bumping Into Broadway”) were shot in Los Angeles, and the production covers a lot of ground. There’s even a fantastic view of the city’s downtown skyline behind the Brooklyn Bridge, dominated by the Woolworth Building, which was the tallest structure in the world at the time. (Construction on the Empire State Building was still three years in the future.) Given the film’s nostalgic worldview, it’s all too appropriate that it now serves equally as entertainment and history.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.