Spielberg’s Jaws adaptation cut the mafia and sex subplots—and made movie history

Image: Graphic: Jimmy Hasse

For all the variety in summer blockbusters, the category has a few attributes that seem pretty much mandatory whether you’re talking about the latest special-effects extravaganza, a broad comedy, or any other genre of crowd-pleaser. First, there’s a high-concept premise, something easily summarized in a couple of sentences (or, in today’s intellectual-property-heavy world, grasped from the title alone); this is not a season for domestic dramas or slice-of-life films. You’ll need a few big set pieces, coming at set times—you can adjust your watch to the formula. And, unless it’s a franchise establishing a cliffhanger, the film will almost certainly conclude with a happy ending, the hero victorious.

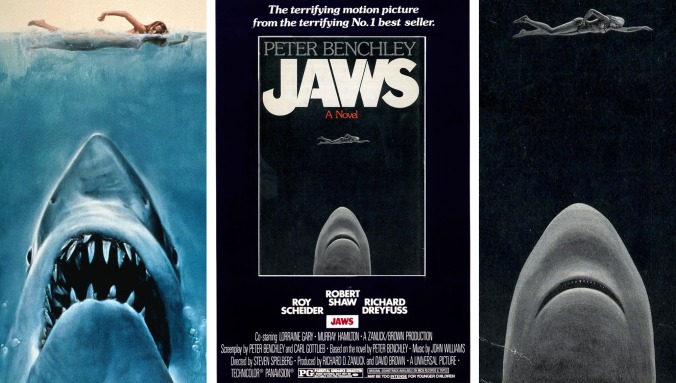

Blockbusters have been Hollywood’s dominant focus for more than 40 years, ever since Steven Spielberg adapted Peter Benchley’s Jaws into a historic hit and basically created the modern template (Star Wars, two years later, cemented it). So here’s a hypothetical: What if Spielberg had adapted Jaws as originally written, a cynical story with subplots of corruption, class conflict, and an unhappy marriage falling apart, all of which lead to a downbeat ending? Would the entire history of modern cinema be different?

As recounted in the book’s 30th anniversary edition, when producer Richard Zanuck discussed the adaptation with Benchley (who co-wrote the script), he explained, “This picture is going to be an A-to-Z adventure story, a straight line, so we want you to take out all the romance stuff, all the Mafia stuff, all the stuff that’ll just be distracting.” Had the film traced a meandering, political line, as was common enough in 1970s Hollywood, would we have even had the blockbuster era? Audiences of the time embraced challenging works, but it’s hard to imagine them packing theaters—to the gills, so to speak—for something less morally black and white. The formula Jaws laid down has become the standard.

To be sure, the film closely follows the book. As Zanuck said, the changes were mostly ones of omission, removing subplots and character traits that could be explored in a novel but which would’ve diluted the main story in a two-hour film. Those omissions, however, materially changed the tenor of the story.

The plot, as we all know, involves the (fictional) seaside town of Amity, a place that lives or dies by its summer season, when visitors and seasonal residents give the local economy the only juice it’s going to get all year. “Lives or dies” is hardly hyperbole; the book warns that full-time residents wouldn’t be able to weather two slow summers in a row, and would move away en masse. Into these blue waters—duh-duh duh-duh—comes three tons of shark, a 20-foot great-white killer with unimaginable strength, a bottomless appetite, and a mouth of butcher knives. As it picks off swimmer after swimmer, police chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) wrestles with whether to protect the people at the expense of crippling the town by closing the beach on the crucial Fourth of July weekend. The only way for it to be safe to go back in the water is for Brody, with the help of an oceanographer named Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) and Quint, a grizzled sea captain (Robert Shaw), to find the shark, and kill it.

Jaws is an effectively simple story. Amity’s economic crisis explains why killing the fish is an immediate necessity, sharks otherwise being fairly easy to avoid on land. The book complicates this issue by adding an element of political corruption to the beach-closure decision. Amity mayor Lawrence Vaughan (played by Murray Hamilton) is also the region’s biggest real-estate honcho; not only does he stand to be wiped out if a shark scares people from buying or renting in the area—“Ever tried to sell healthy people real estate in a leper colony?”—but it would also put him in danger with the mob. A gangster previously saved him from bankruptcy, and Vaughan has been returning the favor by buying seafront property, assets the shark is threatening to make worthless. (Poor mayor: getting it from both loan sharks and shark sharks.)

A minor subplot of the book is Brody trying to uncover Vaughan’s secret business partners; nothing comes of this, and it’s entirely unnecessary to the story. That Amity needs the beaches open to survive is motivation and dramatic tension enough. Making Vaughan corrupt renders him less complex than he is in the movie, where he is genuinely trying to help his town, and genuinely devastated when he urges sunbathers into the water, only for the shark to attack. (His son was among those swimming.)

Jaws was released at a time when cynicism about the government ran high—this was not only the era of Watergate, but also The Parallax View, All The President’s Men, and The Three Days Of The Condor—and this subplot would have fit into the tenor of the times had Spielberg carted it over. That he didn’t made narrative sense, but if he had, would future blockbusters have followed in making social commentary a part of their dynamic?

A more substantial change in the adaptation revolves around Hooper, but to understand his function in the book, we should start with Ellen, Brody’s wife (Lorraine Gary). In the film, Brody’s new to his job; this is his first summer in Amity, after a stint with the NYPD. (He’s also afraid of water, something both versions mention, but neither of which present as a significant handicap.) He has a few years of tenure in the book, and is far more aware of Amity’s need to avoid bad publicity. The previous year, he and the newspaper publisher downgraded a bunch of rapes to molestations in the police blotter, having “agreed that the specter of a black rapist stalking every female in Amity wouldn’t do much for the tourist trade.” (That kind of racist writing is unfortunately fairly frequent in the book.)

Book Ellen, meanwhile, grew up a rich kid, the kind who summered in Amity. She’s extremely conflicted about this, because not only do the locals reject her, in her mind, for not being raised there, but the wealthy population—a community she longs to return to—has little use for her either now that she’s slumming it in the middle class.

Into this comes Hooper, who in the book is the younger brother of one of Ellen’s ex-boyfriends. She’s immediately attracted to him, both for his looks and for what he represents: “She felt that without some remedy, the part of herself that she most cherished would die. Perhaps the past could never be revived. But perhaps it could be recalled physically as well as mentally. She wanted an injection, a transfusion of the essence of her past, and she saw Matt Hooper as the only possible donor.” Contrast this to the film, where Brody asks her to take their son home after an attack and she responds, “To New York?” Ellen and Hooper have sex in the book. Brody suspects the affair almost immediately, which creates another source of strain when he and Hooper go out on Quint’s boat. At the end, Hooper is eaten alive, in what is clearly positioned as a kind of punishment for his sins (he survives in the film). Brody, in resigned ’70s fashion, decides not to press Ellen about what happened; their marriage of compromise and secrets continues apace.

The Ellen subplot fleshes out Amity, especially the class tensions and uneasy dynamics between locals and visitors, all of which feed into the broader theme of the town’s economic frailty. But like the mob stuff, this isn’t relevant to ol’ toothy, and Benchley is exhibit A in male authors writing extremely unconvincing women, down to physical descriptions (her feet “were perfect enough to suit any pediphile”). In their supposedly flirty banter, Ellen says she has “run-of-the mill” sexual fantasies: “Just the standard things. Rape, I guess, is one.” (“Is he… you know… big?” Hooper asks. “Is he black?”) She also speculates that it’s “every schoolgirl’s fantasy” to be a prostitute, “to sleep with a whole lot of different men.” None of this made it into the movie, thank god. Brody and Ellen have a happy and affectionate relationship—“Want to get drunk and fool around?” she asks early on, a rare example of a middle-aged movie couple getting to be sexual—and Brody and Hooper partner up from the get-go.

Even Quint gets a little more spark in the movie. The book’s version is stoic; he takes the job for the money, and is not particularly fond of rich-kid Hooper or Brody. Robert Shaw’s magnificent performance shades him in tremendously, notably with a famous monologue that explains his Ahab-like tendencies (such as smashing the radio to prevent Brody calling for backup). This, one of the most famous scenes of the film, was written by Shaw, and as such doesn’t appear in the book. (Neither does Jaws’ most famous line, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat,” which started as an on-set in-joke.)

The film of course ends with Brody exploding the shark—an immediate release of tension that countless action and horror films would mimic in some form over the coming decades. There’s no such euphoric moment in the book, which is so muted that I had to read the passage several times to confirm the shark actually dies from the wounds it sustained. The book’s weary closing also feels very ’70s, while the movie’s is modern. It was another lesson blockbusters would learn: Don’t go for subtlety; go out with a bang.

The omissions and additions tell you all you need to know about Spielberg’s first masterpiece. Everything in the film is there to make it sleeker and more powerful. In that way, it’s not unlike its title monster.

Start with: I feel like I should be dragging my fingernails down a chalkboard: “You all know Jaws, know what it does.” By now the lore around the movie is as famous as the story itself—how Spielberg, all of 28 at the time, permanently catapulted himself to the top of Hollywood with this success; how he worked around malfunctioning shark props by implying the great white’s presence in the film, a solution that had the handy byproduct of ratcheting up the suspense. (Why don’t all directors do this? It’s essentially making better movies for lower budgets.) Suffice to say, it holds up magnificently. It’d be a classic even if it wasn’t one of the most influential movies ever made. (Quint’s death was the most upsetting thing I had ever seen when I first watched this as a kid, and I still don’t like to swim at night because of this movie.) The book, in contrast, is sillier and more disposable, but it functions fine as a beach read, albeit the kind to make you want to leave the beach.