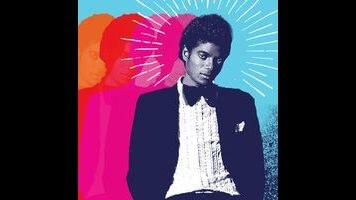

Spike Lee looks back at the moment when Michael Jackson went Off The Wall

In 1971, Marvin Gaye released What’s Going On, an ambitious, socially conscious LP that he had to fight with his bosses at Motown to make. That same year, Stevie Wonder finished up his Where I’m Coming From, the first of a string of 1970s album that he wrote, produced, and performed mostly by himself, using his leverage as a hitmaker to get Motown to leave him alone. Meanwhile, around the same time, The Temptations had begun pioneering a sound that came to be known as “psychedelic soul,” stretching out on singles like “Ball Of Confusion” and “Papa Was A Rollin’ Stone.”

This freedom to experiment was paid for in part by The Jackson 5, Motown’s newest and youngest stars, who in 1969 and 1970 recorded four straight Billboard No. 1s: “I Want You Back,” “ABC,” “The Love You Save,” and “I’ll Be There.” While the label’s other acts were rebelling against their leader Berry Gordy’s rules and regimens, the Jacksons were proof that the old blueprint still worked: If musicians let Gordy groom them, train them, and provide them with songs, they could get famous. All it cost them was their creative freedom.

Spike Lee’s documentary Michael Jackson’s Journey From Motown To Off The Wall explains how The Jacksons’ frontman stealthily—almost imperceptibly—achieved his independence. This is the second doc that the Jackson estate has hired Lee to helm, and it’s a marked improvement over the one made to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Bad. That film, while fleetingly insightful, was overlong, laboriously documenting the creation of every song and every video. From Motown To Off The Wall is shorter and fleeter, even though it covers a lot more ground.

Lee opens with a subtle sort of overture, holding back any kind of narration or talking-head interviews for a few minutes so that he can show short clips of Michael Jackson at the end of the 1970s and the start of the 1980s—ending on him in concert with his brothers, half-pretending that he’s not going to do a medley of Jackson 5 hits because they’re “old.” Then Lee jumps right into the story, moving swiftly from the heyday of the J5 to the startling moment in 1975 when the Jacksons turned their collective back on Gordy and signed with Columbia Records’ Epic imprint.

Nearly half the film goes by before Lee gets to Michael’s groundbreaking, multiplatinum 1979 album Off The Wall, at which point he follows much the same formula that he did with Bad 25, going through the LP song-by-song. Interviews with some of the musicians and writers who worked on the record—along with testimonials from Questlove, John Legend, Kobe Bryant, John Leguizamo, and more—help explain how what initially seemed like just another slick set of pop and R&B songs became a phenomenon.

Also like Bad 25, From Motown To Off The Wall particularly emphasizes what Michael Jackson meant to the black community during the time period covered in the documentary. Early in the film, former Motown executive Suzanne De Passe talks about how The Jackson 5—with their frequent TV variety appearances and Saturday morning cartoon—gave African-American kids their own equivalent to The Mickey Mouse Club. Then came The Jacksons’ massive, eyebrow-raising Epic deal, which at the time was a risky investment in the persistent popularity of an act that white America assumed was played-out.

At first, the naysayers seemed to be right, as The Jackson 5 struggled with a new home and new expectations. But then the band’s third Epic album, 1978’s Destiny, produced the Top 10 pop hit “Shake Your Body (Down To The Ground).” That same year, Michael Jackson was the highlight of Sidney Lumet’s otherwise disappointing movie version of the musical The Wiz; and he also became a high-profile regular at New York’s hottest disco, Studio 54. It wasn’t just Epic’s gamble that was starting to play off. It was as though all the years that young fans followed one cute little boy’s career were retroactively becoming time well-spent, as he matured into manhood.

He capped off that flurry of activity by planning and recording Off The Wall with one of his Wiz collaborators, producer Quincy Jones. The album features club-ready tracks like “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough,” roller-skating pop jams like “Rock With You,” tearjerking ballads like “She’s Out Of My Life,” unclassifiable genre-bending hybrids like the title track, and even a song, “Girlfriend,” written for Jackson by Paul McCartney. In Lee’s film, the panel of expert interviewees marvels at the album’s variety and ambition.

One talks about how black artists—just like black athletes—sometimes see their accomplishments diminished by critics and reporters who praise their “natural gifts” and ignore the years of training and calculation. But the archives and notes that Lee taps for From Motown To Off The Wall reveal how carefully Jackson thought about his music and his public image—right down to his plan to ditch his child star persona by reinventing himself as someone mysterious and “magic.” One of the best anecdotes mentions how “She’s Out Of My Life” writer Tom Bahler hesitated to give the song to Jackson because he was saving it for Frank Sinatra, until Jones reassured him that after Michael sang it, “Sinatra will do it anyway.” That’s some kind of confidence right there. Or maybe just awareness.

The narrow scope of both Bad 25 and now From Motown To Off The Wall has advantages and disadvantages. The upside is that Lee is freed from having to delve into some of the more bizarre, unsavory, and controversial aspects of Jackson’s later life and career. The downside is that both docs are more or less just extended ads for Sony’s anniversary reissues of Michael’s albums. This new one also has some qualities of hagiography, establishing how with Off The Wall the artist’s singular genius shown through, unfiltered, for the first time—leading eventually to Thriller, an unparalleled commercial blockbuster.

Still, there’s plenty of Lee’s personality in this movie: from the snippet of a film about disco that he shot in 1977 to the eclectic assemblage of people he talks to about Jackson and Off The Wall. Who else would think to ask Misty Copeland about Michael’s dancing, or would take a few seconds to ask The Wiz screenwriter Joel Schumacher about writing the scripts for Car Wash and Sparkle? (Lee even gets a few comments from David Byrne, a literal Talking Head(s).)

The use of the word “journey” in Michael Jackson’s Journey From Motown To Off The Wall is key to what Lee does with what is, essentially, a corporate assignment. There’s a strong sub-current to the film that isn’t about the album per se, but about how Jackson spent a decade quietly watching, listening, and strategizing while friends like Marvin and Stevie made bigger statements—and about how the truly hip were paying attention all along.