Spike Lee’s Chi-Raq is a fumble worth making

Out of all the wildly gifted black movie directors this country produced during the latter part of the last century, Spike Lee is the only one who ended up getting something like the career he was owed, and the only one who’s been able to hold on to what should be a basic right extended to all artists: the right to fail. His work swings unpredictably from fresh to lame, often within the space of one movie, but sometimes that’s just what you get with a director who hits the sublime by risking ridicule (see: the kick-off of Do The Right Thing or the end of 25th Hour), and whose movies never feel more real than when they overheat with theatrical flourishes. Lee always speaks his mind, but then again, so does the guy on the street corner with the UFO sign; the difference is that when Lee hits on something cogent, even in his bad movies, he lets it out so hard that it makes the entire idea of completely didactic filmmaking seem thrilling. And, anyway, if we can’t tolerate bad art, how can we ever expect the good stuff?

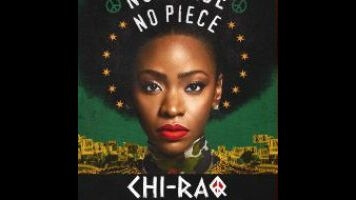

Chi-Raq, Lee’s modernized take on Lysistrata, is mostly bad art; it’s about an hour too long, sometimes leadenly unfunny, and set in Chicago, a place the Brooklynite director has no feel for. Scripted largely in rhyming verse by Lee and Kevin Willmott (C.S.A.: The Confederate States Of America), it’s a movie where a viewer would be hard-pressed to point out anything that really works; it’s too gooey to bite as satire, and too much of a cartoon to be a sincere cri de coeur for the Second City’s metastasized gang culture. Some scenes are literal sermons, others are one-joke skits. And yet it’s hard not get at least a little energized by the whole thing, a blend of raunch, agitprop, theater, and documentary that sometimes plays like Lee’s answer to the absurdist, antiauthoritarian sex-and-politics movies of Dušan Makavejev (W.R.: Mysteries Of The Organism)—rarely more so that in a sequence that finds the stone-faced Chicago Police Department trying to lure a band of radicalized women, girded in chastity belts, out of a National Guard armory by blasting slow-jam oldies from a riot PA.

Aristophanes’ play, which premiered in Athens about two-and-a-half millennia ago, has held on really well for something so thick with topical references and disses; frankly, an irreverent update seems like the only way to go. Here, instead of getting the women of Athens and Sparta to withhold sex until their men end the Peloponnesian War, Lysistrata (Teyonah Parris) organizes the women of Chicago to do the same until the city’s gangbangers, powers that be, and business interests find a way to fix its out-of-control gang violence and the broken infrastructure from which it stems. It’d be hard to fault Chi-Raq for fixating so hard on the battle-of-the-sexes angle and on jokes about the Greek classics (plus Dr. Strangelove, still the standard for putting an Aristophanes-esque sensibility on film), since that’s also true of the source material. But barring an extended cameo from Dave Chappelle, whose voice blends seamlessly into the stylized speech of the script, and a climax which, in a movie rife with bad puns, inevitably involves a televised seduction-off between Lysistrata and her gang leader boyfriend, Demetrius (Nick Cannon, surprisingly not bad), Chi-Raq’s non-stop blue-balls humor is mostly tiresome.

But though Lee gives up any claims to sociological credibility somewhere in the middle of the first crane shot, his movie still smolders with concern for what’s happening on the streets of Chicago, bursting into flame in a scene in which John Cusack, playing a stand-in for magnetic South Side activist and Catholic priest Michael Pfleger, shouts out a funeral sermon in front of the black Jesus mural that decorates Pfleger’s real-life parish, Saint Sabina. There probably isn’t a filmmaker around whose skill set is better suited to scenes of people preaching than Lee, given his taste for direct-to-camera addresses, bold statements, and theatrical staging. So though Chi-Raq may mostly fail as comedy (see: two sequences in which white authority figures act out historical-power-fantasy sex games, both interminable), the way it expresses the things it doesn’t find funny still makes for some of the most impassioned filmmaking Lee has produced in a long while, even if it is frequently enveloped in sap. It might be a patience-testing fumble, but it’s one that was worth making.