Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: “Apocalypse Rising”/“The Ship”

“Apocalypse Rising” (season five, episode one; originally aired 9/30/1996)

In which Gowron shows his true colors…

It must be fun working for Starfleet. If you’ve got a ship, you can spend most of your time ignoring communications and trying to dodge diplomatic escort missions (which, as gamers know, are the worst missions of all), but when the shit finally hits the fan, somebody’s going to pick up that red phone, and you damn well answer. It’s even worse if you’re stuck on an undermanned space station just on the edge of a warzone. When we left our heroes, Odo had just revealed the startling possibility that Gowron, the head of the Klingon Empire, and the Klingon who kept popping up on viewscreens throughout the episode calling for what sounded an awful lot like open war on the Federation, is a Changeling. “Apocalypse Rising” picks up a week or two after this, with Sisko and Dax finally return back to the station after a meeting with the higher-ups. Their shuttlecraft is in bad shape, but that’s just the beginning. Sisko calls a briefing soon after arriving home, and gives his crew the bad news: Starfleet has ordered them to infiltrate the Klingons’ most highly secure secret base, and with the aid of a special device no one has ever actually tested before, reveal Gowron’s true nature to his own kind. Which sound like fun.

Actually, since the mission involves Sisko, O’Brien, and Odo getting made-up to look like Klingons, it really is fun, with some solid twists and soul-searching sprinkled throughout. High stakes, big risk action stories provide a wealth of ways writers can keep their audience engaged, from the seemingly insurmountable odds to the cavalier quip in the face of certain death, and one of the advantages to DS9’s on-going Dominion War arc is that it’s a plotline that keeps creating opportunities for what happens next. The moderately serialized nature of the show means that an episode like this one, with its pulpy charms, can sit side by side with a still pulpy, but far grimmer hour like “The Ship” without any real issues of tonal whiplash. Both entries come across as the same show, and not just because of they share opening credits and the same cast; the premise is large enough to allow for multiple possibilities. Better still: It practically demands them.

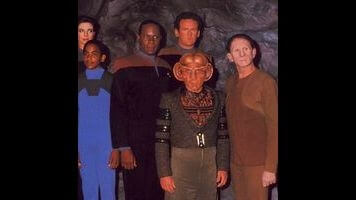

So Sisko, O’Brien, and Odo get made up like Klingons, and with Worf as their guide, they commandeer Dukat’s Bird Of Prey and make their way to Klingon territory. Kira, being pregnant and all, stays behind, which makes for some enjoyable banter between her and Bashir about the frustrations of bearing someone else’s child. (In case you didn’t know, Nana Visitor was actually pregnant for this, and Alexander Siddig was the father.) Plus there’s a bit with Bashir and Jake about how Jake is worried about his father—nothing major, but it’s a good example of how the writers find ways to briefly reconnect with all of the series’ main characters before digging into the main plot. While Sisko ostensibly takes center stage as the episode’s protagonist—he is, after all, the captain, and takes to being a Klingon with a lot more zest than the others. But it’s Odo who serves as the heart of “Apocalypse Rising,” Odo with his unsettlingly solid body, and his newfound doubts about his place on the station.

Obviously the ex-Changeling’s transformation was going to cause some problems for him, but in a way, this latest depression is a manifestation of something that’s been with Odo’s character from the beginning. I’ve gone on at great length in these reviews about what I see as the character’s self-imposed rigidity, his determination to hold to a single idea of himself, and to use that idea to define his purpose in the world. The thing is, that “idea” existed in large part as a reaction to his physical nature; Odo’s obsession with the law, with order and rules, came about because his physiology left him perpetually in flux, a muscle that needed to be constantly flexed. In order for him to maintain his persona, he was literally required to concentrate on maintaining it at all times, which means it’s only natural that he’d come to define himself in such simple, straightforward terms. But now the primary factor which drove his initial development is no longer relevant. It’s only natural that he begins to question the rest of the choices he’s made, and that sort of questioning leads him to the self-doubt that plagues him through much of the episode. When Sisko comes to see him about the mission into Klingon territory, Odo is savoring the bubbles in his drink, and trying to enjoy his new senses. But when Sisko tells him he’s needed, Odo tries to back out. He used to know exactly who he was, and now that’s not true anymore, so he assumes he doesn’t have anything left.

What’s effective about this is that it’s never over-emphasized. We get a couple scenes of Odo acting depressed, but there’s no question of him being included, and when his clumsiness puts the mission in jeopardy, it’s less a matter of ineptitude than it is his insecurity coming to the fore. After some fun Klingon training from Worf (always yell up close, and do not hit another Klingon with the back of your hand unless you want a fight to the death) and a brief, brutal example of Dukat’s combat philosophy (he doesn’t have much problem destroying Klingon ships), our four heroes are beamed over to headquarters, where they join the Klingon party already in process. It’s as crazy as you’d expect, with bunch of warriors (both male and female, although more men than women as far as I could tell) drinking and shouting and punching each other; everyone’s waiting for Gowron to arrive to induct them into the Order of Bat’leth, but as Worf explains, the party beforehand is almost as important as the induction ceremony, because it serves as a test of fortitude for the warriors involved. If you can manage to stay drinking and fighting for hours on end, and attend the next day’s ceremony without missing a step, then you’ve earned your place. Our heroes cheat a bit by taking an anti-intoxicant beforehand, but it’s still a long night, and Sisko manages to get in fight or two while waiting. (The first fight is when he overhears a Klingon boasting about murdering one of Sisko’s old friends; the rest are probably just to keep him awake.)

Odo’s mistake: When it comes time to set the devices in place that are supposed to reveal Gowron’s true nature, Odo inadvertently drops his, and then needs Worf’s intervention to come up with a lie to cover for the drop. The fumble is something that could happen to anyone, but Odo’s terrified expression indicates he’s still having to struggle to convince himself he’s up to this. It’s a quick moment, though, and Odo soon recovers; later, when a Klingon gets in his way, the constable manages to shove the guy aside without too much trouble. Then everything goes to hell when General Martok finally recognizes Sisko, even with his Klingon make-up on. (We last saw Martok at the start of the previous season, leading the Klingon force that ostensibly arrived at DS9 to help in the war against the Dominion.) Everybody gets captured, but some fast talking by Sisko and Odo seems to convince Martok of Gowron’s duplicity. The general helps them escape and leads them back to the hall of warriors, where Worf challenges Gowron to a battle to the death, it being the only way left to expose the Changeling’s true nature.

Only Gowron-as-Changeling seems a bit too simple now, just as it did when the twist was first announced, and it’s Odo, having been held back by Martok before the battle begins, who puts it all together. That’s crucial; not just that Martok is the Changeling and Gowron is not, but that Odo is the one who figures out what has happened, and is able to alert the others before everything falls apart. I’m not a huge fan of twists stacked on top of twists (it’s not a terrible plot trick, but after awhile, the whole thing becomes so top-heavy that you’re more invested in where the next betrayal is going to come from than you are in the actual characters), but this one works well enough. It’s certainly the sort of lie the Federation would believe, and it’s one more way to stick the knife into Odo’s back, by making it even more explicit just how little he knows of his former people.

The real key, though, is that Odo is the one to see through the charade, because he was the one who provided the initial intel that set Sisko and the others on this mission. If someone else had figured it out, or if Gowron had been killed before the truth was revealed, Odo would’ve been wrecked, possibly beyond repair—the shame of mishandling the one positive to come from his time in the Great Link, of being used to betray what are now his only true friends, would’ve been devastating for him, and bordering on sadism from a narrative standpoint. (There’s nothing wrong with making characters suffer for a reason, but too much suffering, and it becomes almost farcical.) Instead, Odo realizes the truth, and forces the fake Martok out in the open, where he’s quickly despatched by Klingon phaser fire. Gowron, pleased at having a traitor removed from his ranks, sends Sisko and the others back home (after praising Odo and getting a few cheap shots at Worf, who totally kicked his ass), and when they’re back at the station getting their faces put back together, Bashir tells Odo he can make him look more human or Bajoran or whatever, if he wants to. Odo stays with his old face. It’s about as direct a sign you could hope for that he once again remembers who he is.

Stray observations:

- To my mind, Deep Space Nine possesses the ideal balance for most ongoing serialized TV shows: Too little serialization and DS9 would lose its narrative advantages, and too much means risking a lot of “let’s stall for time” style entries that plague stuff like The Walking Dead. For my money, the only effective heavily serialized show on the air right now is Breaking Bad, which has the benefit of Vince Gilligan and his writing staff, and more importantly, a narrative that specifically lends itself to heavy serialization. Content should dictate structure, not the other way around, and too many shows these days see that serialization is the new thing and latch onto it as though the style in and of itself is justification enough. All of which is to say, the balance DS9 has achieved works pretty damn great.

- I wonder way Martok held Odo back from the confrontation at the end. Given that, had Worf succeeded, Sisko, O’Brien, and Worf would’ve almost certainly been killed in the ensuing mob, are the Changelings still invested in Odo’s safety? And if so, does that mean they still consider him one of their own, all words to the contrary?

- High Changeling body count this week. That will probably not go over well.

- O’Brien is a block-faced Klingon.

- It makes sense that Martok would recognize Sisko and the others even with their new faces. As a Changeling, he expects the familiar to take many different forms.

- “I could do without the ridges, but I kind of miss the fangs.”—Sisko, who really does make an excellent Klingon.

“The Ship” (season 5, episode 2; originally aired 10/7/1996)

In which O’Brien loses a friend…

People die all the time on Star Trek. The high mortality rate of red-shirted extras in the original series has long been part of franchise lore, but the truth is, it never really mattered what color your uniform was; if you weren’t a main cast member, and a threat needed to be proven, then the odds were against you. It was even worse if the audience was given a chance to get to know you just enough to lend your death dramatic impact. In “Balance Of Terror,” one of the high points of the original series’ first season (and the episode that introduces the Romulans), the story begins with Kirk officiating a wedding between two crew members we’ve never seen before. Then everything goes to hell, and in the course of the hell-going, one of those crew members is killed. It’s the most blatant, obvious trick imaginable, and, as was often the case with TOS, there isn’t a lot of subtlety to the way it’s deployed. But if you can get past the corniness, and the artifice, the trick still fundamentally works. Empathy is a powerful tool, even (and often especially) when deployed bluntly. But even more than that, I think there’s something personal about those broadly drawn corpses. Were we to find ourselves on a star ship or a space station or an alien world, odds are, we wouldn’t last much longer than they did.

DS9 is generally more subtle and complex than its forebears, but in “The Ship,” the writers demonstrate they still know the old tricks, and are more than willing to use them when the situation warrants. In the cold open, we see O’Brien and a relatively new guy (who’s apparently been on the show twice before, although I didn’t recognize him) named Muñiz (F.J. Rio) walking around and looking at the rocks. The two banter, and there’s an obvious affection between the two men that immediately makes you wonder why, exactly, we’re seeing this. Casual conversations pop up on the show all the time, but they’re almost always between main characters, or a main character and a recurring character. Muñiz ribbing O’Brien about getting winded during the hike isn’t just a casual piece of texture before the plot begins in earnest. There are only 40 minutes per episode to tell a story, and that’s not much time at all; every scene counts. (Unless the script is terrible and it’s all padding, of course, but this scene doesn’t come across as padding.) So from the very start, we’re given special reason to notice Muñiz, to care a little about him, and to wonder why we care.

So, yeah: This isn’t subtle. But “The Ship” is an excellent hour, and that directness of intent works very much in the episode’s favor. I’m not saying I knew Muñiz was going to die; I spent a lot of the time really hoping he wouldn’t. But by putting the manipulation front and center, by reminding us again and again of how much Muñiz’s injury and eventual death bothers O’Brien and the others, the script takes the cliché of the doomed guest star and makes its fundamental predictability work in the story’s favor. The point isn’t that Muñiz is going to die. The point is that he isn’t the first good person to die in the Dominion War, and he won’t be the last. For Sisko and O’Brien and Dax and Worf, every fresh face on the station is just another potential liability, another name to add the list in their memory that keeps getting longer. Muñiz and the others who die here are killed not just for the audience’s direct benefit (lucky us), but to show how their deaths affect the characters we’ll be seeing week in, and week out, until the end of the series. It’s not the most organic plot development in the world (it’s not just Muñiz, but another guy on the ground who gets it without an exist line, and a whole shuttle full of fresh faces; good thing this didn’t happen when Kira was piloting, eh?), but the way it’s deployed, and the slow, painful manner of Muñiz’s death, transcends the limitations.

As to the actual story, it’s a good one: While doing a routine mineral survey on a Gamma Quadrant planet, Sisko and his team witness the crash of a Jem’Hadar ship. They quickly investigate, and find the entire crew inside, dead before their ship hit the atmosphere due to an engine malfunction. Before anyone can figure out the best way to get the ship back in the air again, more Jem’Hadar arrive, destroying the shuttle orbiting the planet and trapping Sisko, Worf, Dax, O’Brien, and the severely injured Muñiz inside the ship. A Vorta named Kalina (Kaitlin Hopkins) offers to parlay with Sisko, but it’s just an attempt to distract him long enough for a long Jem’Hadar soldier to beam into the ship, where he’s killed before he can find whatever it is he’s looking for. And he was looking for something. Sisko quickly realizes that Kilana and the Jem’Hadar aren’t after the ship so much as some mysterious cargo that the Vorta refuses to identify.

So now we have a mystery and a siege situation, with a plausible reason for why the Jem’Hadar (who vastly outnumber and outgun Sisko and the others) don’t immediately attack. The mystery won’t be solved until the very end, which means that while we wait, we get to see how these characters hold up under pressure. While they don’t crack as badly as, say, a bunch of strangers holed up in a house against an army of zombies, the strain shows. The Jem’Hadar constantly bombard the ship with explosions that are far enough away not to do any damage, but close enough to make your teeth rattle, and of course poor Muñiz is dying over in the corner, going from conscious and coherent to hallucinating his childhood and the fireworks of Carnival. So things get a bit tense, most notable between O’Brien and Worf. Worf insists that Muñiz be told he’s dying, so that he can face death with honor; O’Brien refuses to accept this, believing that there’s always hope. It’s easier to side with O’Brien, but given Muñiz’s gradual descent into fever and death, it’s hard to fault Worf’s more pragmatic approach. Both philosophies are a way to put meaning into an event that’s fundamental to our existence, but at the same time unfathomable. To Worf, honor comes before all. To O’Brien, it’s hope.

Sisko is having his own problems trying to hold everyone together, and when he finally realizes what the “mysterious cargo” is, it’s too late to do much about it. There was a Changeling on the ship, hiding in plain sight the whole time, and when he or she isn’t able to return to liquid form in time, it collapses, turning into a pile of ash. I’m not exactly sure why the Changeling didn’t try and escape on its own; if the crash had rendered the creature unconscious somehow, how would he or she have been able to maintain a shape that blended into the ship’s bridge for so long? And if he or she was conscious the whole time, I’m not sure I accept that such a powerful being would’ve been too frightened to contact Sisko directly. But then, there’s no way of knowing how bad the Changeling’s injuries were—and besides, this does speak to one of the truths of the Founders that we’ve known since their introduction: They do not trust the solids. Not even when they have to.

In the end, Sisko gets the ship he wants, and he and Dax tell each other it was worth all those deaths, but that doesn’t make it easier. It shouldn’t. What’s especially painful is how easily all of this could’ve been avoided with a little more trust, a little less paranoia. If Sisko had known there was a Changeling aboard the ship, he would release the creature; at least that’s what he tells Kalina, and I believe him. (They certainly couldn’t have gotten off the planet with the Founder in tow.) And if he’d released the Changeling, Kalina would have let him leave with the ship, which is all he wanted in the first place. But because war doesn’t work like that, a bunch of people are dead who didn’t need to be, and Sisko can’t stop staring at the list of names. And in the hold, O’Brien and Worf sit in guard over Muñiz’s corpse, paying last respects and making sure the body stays safe. They’d done this before. They’ll do it again.

Stray observations:

- I cried at the end. I was doing okay until Worf showed up, and then Niagara Falls.

- Kalina showed a bit more cleavage than the Vorta usually do (in my limited experience with Vorta). It’s an interesting negotiating tactic; she’s not trying to seduce Sisko, but she does go to great lengths to appear vulnerable.

- Forgot to mention: The Jem’Hadar all kill themselves after the Changeling dies, for failing to protect one of their gods. And they’re so normally low-key, too.

Next week: We dive into the improbably named “Looking For Par’Mach In All the Wrong Places,” and follow Jake into war with “…Nor The Battle To The Strong.”