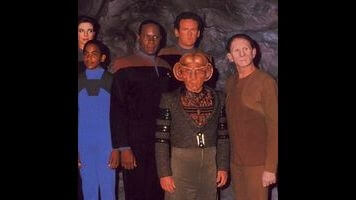

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: “Cardassians”/“Melora”

“Cardassians” (season 2, episode 5; originally aired 10/24/1993)

In which you can go home again, but you really don’t want to

We’ve seen how the Cardassian withdrawal affected Bajoran politics, leaving ambitious Bajorans the necessary chaos to achieve their ends, while the leaders of the revolution floundered in the absence of a clear enemy. But while Kira has explained the horrors of the occupation effectively enough, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine hasn’t given us a sense of what the new world order means to the average citizen of Bajor. This isn’t a flaw; DS9 isn’t a sociological survey. But it is a possible source for new stories, given the show’s willingness to present the reconstruction of Bajor in a positive-but-still-cynical light. “Cardassians” doesn’t spend a lot of time on the planet, but it does introduce a subject we haven’t dealt with before: the Cardassians left behind in the chaos of the retreat. Specifically, the Cardassian children. On a world where their kind is known primarily as merciless aggressors, these orphans are the victims of forces beyond their control, doomed to a lifetime of apologizing for actions they had no hand in. They’re statistical oddities, points on a graph that don’t fit a standard arc, which makes them excellent fodder for drama.

“Cardassians” delves into this to an extent, and for a while, the episode seems to be about the challenges facing the orphans in the reconstruction. But then the whole thing turns out to be about something else entirely. I’m not sure if there’s a term for this, but it’s something I’ve seen on plenty of genre shows, stories that start off dealing with complex, difficult situations before everything gets simplified into a clear-cut case of “Bad guy messed us up.” That’s not exactly what happens here, as Gul Dukat’s duplicity doesn’t erase the stricken expressions Bashir sees on Cardassian orphans while visiting Bajor; nor does it take away from the fact that Rugal, a Cardassian boy raised by Bajoran parents, is forced to leave the people he knows and loves and return to Cardassia with his biological father. But it softens the blow in a way that undercuts the impact of these facts. The brief courtroom scene at the episode’s climax treats Bashir’s revelations about Dukat as if they were some kind of shocking truth, but these revelations are essentially meaningless in the context of what had, up until then, been the story’s main focus. The issue was, does Rugal belong back at home with his own kind, or should he stay with his Bajoran parents? Dukat’s trickery doesn’t enter into it. Hell, if anything, finding out he was manipulating events behind the scenes makes it seem even more like Rugal should stay with his adoptive parents, given that this most likely means the accusations against those parents were part of Dukat’s scheme.

I almost wonder if the ending was a compromise between what the series was aiming for, and what it could actually achieve. It’s something that happens fairly often on television, especially on a show that isn’t quite sure how dark it wants to get. DS9 had demonstrated its willingness to go grim, but maybe destroying a child’s life was a little harsher than anyone was comfortable with, and so we got the silliness about Dukat and his evil plan. It’s not bad as evil plans go (it shows a remarkable amount of cunning, really), but, again, it doesn’t change any of the issues here. It makes Kotan Pa’Dar look even more the victim, but his connection to Rugal was never in question, and the debate over the suitability of Bajoran parents for a Cardassian child never gets going. The episode goes so far as to give us the standard-issue Trek “hearing,” but, as mentioned, the proceedings are short-circuited by Bashir and Garak’s sudden appearance. By the time Rugal leaves with Pa’Dar, you have to work to remember all the angst that built to this moment. Rugal, who spends most of his screentime making his feelings about Cardassians very, very clear (he’s not a fan), doesn’t even seem all that upset about leaving. At the very least, he’s resigned himself to whatever happens next, and while I completely accept this as a resolution, it feels like we missed a step, in seeing him go from hating his biological dad to being kind of okay with it. All the time we spend with Bashir and Garak, tracking down Rugal’s adoption records and uncovering the secret plot, Rugal is going through drama back on the station—and it’s hard not to feel short-changed.

I can’t criticize the episode too harshly for this, though, because while Rugal is interesting in concept, he is (like so many television teenagers) pretty dull in practice; not that anyone would have an easy time competing with the grand return of Garak. Last time we saw our favorite Cardassian sonofabitch was back in the “Past Prologue.” It’s been too long, but thankfully, Garak hasn’t lost any of his charm. Andrew Robinson is as sharp and sexually ambiguous as ever, and his presence helps elevate the Dukat storyline to a high enough leval that its essential pointlessness loses a lot of its sting. Garak is a rarity in Trek, a character whose motives are never entirely clear; like Bashir, we’re pretty sure he’s on the “good” side, and his actions so far have upheld this, but he’s just mysterious enough to make you wonder what else is going on behind those smiles.

Maybe “ambiguous” is the wrong word. Maybe it’s more that Garak is someone with his own agency, and his own goals, and every so often he wanders into this silly little TV series and livens up our dreary lives. We learn a few things about him we didn’t know before—namely that he and Gul Dukat have a history—but if there’s any substantial change between this episode and “Past Prologue,” it’s that Bashir is much more confident and direct. Generally speaking, this is a good episode for the doctor. He oversteps himself once or twice (and Sisko is hilariously terrifying each time), but his instincts are good, and it’s nice to see him forcing the always slippery Garak to be more specific in his insinuations.

As for the rest of the hour, Rugal’s brief time with the O’Briens is illuminating. For once, O’Brien manages to look less sympathetic than Keiko; the chief engineer makes a derogatory comment about letting Rugal play with their daughter, and Keiko shuts him right the hell down. Then O’Brien spends some time with the kid, and, eventually, time with Pa’Dar, and both scenes work well enough, although Rugal isn’t all that compelling. (His situation is compelling, but as an individual, he’s tedious.) Given the title of the episode and the presence of Gul Dukat lurking around the edges, it’s surprising how little Kira is involved in all of this; I think we see her nodding at some point, and I’m sure she provides exposition, but she stays out of the main action. That leaves O’Brien to represent the “I hate Cardassians” faction, which he does with aplomb. Having him hear Rugal explain why he hates Cardassians and why he doesn’t consider himself a Cardassian—despite having the standard issue corpse-skin and assortment of facial spines—makes for a great contrast.

That’s as far as that particular drama goes, though. While “Cardassians” is entertaining, buoyed by Garak’s charms, a thorny premise, and a mystery which only becomes hollow in retrospect, it entertains issues it has no serious interest in exploring, and that can’t help but be disappointing. In the episode’s defense, the Cardassian orphans aren’t a problem that’s easily solvable, and we’re at least given an ending that isn’t happy for everyone. But this feels incomplete, with too much focus put on the trees while the forest just stands there, staring, asking when it can go home again.

Stray observations:

- I like when Rugal whines, “I didn’t do anything wrong,” after he bites a dude in public. Of course, he probably doesn’t think biting Garak is a crime since he believes all Cardassians deserve what they get. I can’t imagine the psychological toll of loathing your own species. Not having some issues or concerns, but actively despising what you are to the point of claiming you’re something else. It’s reminiscent of the black Klu Klux Klan member in Shock Corridor, but while the episode raises the issue, it never does anything with it, preferring instead to focus on Bashir and Garak’s detective story.

- Garak makes a point of saying how odd it is that a race as devoted to record-keeping and specificity as the Cardassians would leave so many children behind for no reason. This is one of the reasons he and Bashir work to uncover the secret behind Rugal’s “adoption,” but we do see other orphans on Bajor. Are they all pawns in some Cardassian official’s power play, just waiting to be called into service?

- Sisko is so much fun when he plays authority figure: “Don’t apologize. It’s been the high point of my day. Don’t do it again.” (He also has terrific pajamas.)

- “I never tell the truth because I don’t believe there is such a thing.”—Garak, bein’ awesome.

“Melora” (season 2, episode 6; originally aired 10/31/1993)

In which you can take the girl out the wheelchair but you can’t take the oh now I hate myself.

Whatever reservations I have about “Cardassians,” it’s miles above the second half of this week’s double feature, a mediocre slog weighed down by an irritating guest star and some cheesy, grating romance. I’m not sure if I’d say this is the worst episode of DS9 I’ve seen yet, but it’s easily in the bottom five and its biggest crime is that it’s annoying in a boring way. This has all the hallmarks of an original series Star Trek episode, without any of the camp or Leonard Nimoy to take the edge off; there’s a woman constantly picking fights with anyone she thinks is trying to hold her back, there’s a regular ensemble member having a supposedly deep relationship with someone we know we’ll never see again, and a guest star flirts with a major life choice in a way that makes it obvious she’ll never actually go through with it. It’s so “blah” I’d completely forgotten about it by the time I sat down to write this review, and I watched it two days ago. There’s a Quark subplot which is mildly amusing, and not every part of the main storyline is absolutely awful, but “Melora” is as disposable as they come.

The biggest problem is Melora (Daphne Ashbrook) herself. An Elaysian ensign working her way up the Starfleet ranks as fast as she possibly can, Melora comes from a planet with a very low gravity level, which means she needs special equipment and modifications to get by in a standard gravity environment. That raises a question (and you’ll pardon the digression, but there’s little about this hour to talk about otherwise): What constitutes “standard gravity” in this reality? I mean, I basically just made up that phrase for the sake of context, as it’s not something that’s ever really discussed at length in any of the Trek shows. The Federation spans far enough you’d think that this amount of differentiation would come up on a somewhat routine basis—and, it should be mentioned, Bashir handles the challenge without acting like it’s completely beyond his abilities. And yet he and O’Brien treat this as something new. (Also, one of Melora’s defining traits is her isolation). It’s always funny when a Trek show takes a scientific idea it normally ignores, like, say, different atmospheres, and highlights it for a single episode. In a way, it’s like how Melora is hugely important to Bashir for this hour, even though we’ll never hear about her again.

Sigh. I guess I should talk about Melora, then. I wasn’t much impressed. Characters with disabilities, when they’re presented poorly, tend to go one of two ways: Either they’re of the helpful, friendly, “it’s okay if you feel awkward around me, I’m here to teach you life lessons” variety that I’m sure popped up on a half-dozen episodes of Full House; or else they’re the angry, chip-on-the-shoulder type that picks fights to prove they can “take it.” Melora lands in the latter category, and as soon as she arrives on the station she’s poking at everyone around her, obsessed with taking umbrage at the slightest hint she’s not capable of performing her duties. This makes her hard to take right from the start, especially considering she’s a stranger to us, a stranger who introduces herself by yelling, for no justifiable reason, at characters we’ve come to care for. Later, the episode tries to soften Melora by first showing how her condition makes her vulnerable—she can fall and not get up—and then demonstrating how her struggles with adversity have driven her to remarkable achievements, like a talent for ordering food at a Klingon diner we’ve never seen before. Oh, and Bashir is totally into her, and we like Bashir, so that obviously means we should give a hoot about whatever Melora’s deal is.

I didn’t, though. I’m not sure how much is the actress’ fault and how much the writing; I suspect it’s a combination of both, but as written, I’m not sure the part is really playable. There’s a flaw that crops up whenever a writer tries to write about a character who has certain innate traits the writer can’t, for whatever reason, empathize with; to compensate, that writer will focus on constantly drawing attention to those traits. Like, if a clueless male writer wants to create a woman, you can expect a lot of talk about physical features and menstrual cycles, since, obviously, being a woman means you think about your boobs and your period all the freakin’ time. That’s the concern with the two aforementioned modes for dealing with so-called disabilities. Yes, being stuck in a wheelchair because you don’t have the muscles or skeletal structure to handle an environment with harsh gravity would be a big deal. But by making it the centerpiece of Melora’s characterization, it ensures she barely exists at all. People don’t tend to go around constantly remarking on aspects of their lives which have been with them for years. Melora is simply an expression of an idea, a symbol made irritating flesh, and, since she’s the one supposed to do all the dramatic heavy lifting here, that gives the episode no place to go.

Like I said, Quark’s plot is fun, although it exists largely so we can have a climax in which Melora uses her magical ability to navigate low-gravity to defeat a bad guy. At least the threat on Quark’s life gives us a scene with Odo, who is sadly missing from most of the festivities this week. (Maybe he and Kira were off having a “Zeppo” moment.) The main story, however, never manages to get off the ground. Bashir sees through Melora’s prickly surface nature (in a conversation which doesn’t play as condescending at all, no sir), the two fall for each other, they float for a while in the low gravity of her apartment. Then he comes up with a “cure,” and she immediately latches on to it, somehow never thinking to question if she really wants to do something to her body that would make it impossible for her to ever visit home again. After having her big moment on the runabout, she decides to forgo Bashir’s miracle treatment, because the ability to float reasonably well is too damn important for her to lose.

Plot summary is the last recourse of the reviewing damned, but I can’t even work up the energy to properly snark this. We did get some back-story from Bashir, which was unsurprising but well-delivered (he played tennis for a while because he watched a girl die), and, um, I mentioned Odo, right? Yeah, let’s move on.

Stray observations:

- Quick, somebody who knows more about evolution than I do: Is it strange that Melora is still recognizable humanoid in shape, despite coming from a planet with gravity so low that it allows for floating? I’d assume she’d be thinner and more delicate; I would’ve enjoyed this episode a lot more if she’d been played by a Muppet.

Next week: We learn a few more “Rules Of Acquisition,” and try to decide what defines a “Necessary Evil.”