Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: "Far Beyond The Stars"

“Far Beyond The Stars” (season 6, episode 13; originally aired 2/11/1998)

In which Benny Russell writes his story…

(Available on Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon.)

Metaphors are fine. Metaphors are, in fact, perfectly lovely and useful and amazing tools when it comes to telling stories. I love a good metaphor, because it’s poetic and just plain fun, coming at your brain sideways in order to trick you into understanding an idea by making you think about something else. A metaphor can be a kind of code, a form of subversion that ostensibly secrets a powerful message inside a seemingly harmless framework. Want to talk about the horrors of war without mentioning a specific conflict? Throw on some fake ears and foley in a few laser blasts, and call the whole thing The Battle Of Kanak’Kar or something. Want to discuss sexual orientation and gender issues? Put everything on another planet, with aliens who look just like us but are slightly different, and have a ball. The metaphor becomes not just a tool inside the text, but the text (or visual medium) itself. It creates a cushion of distance between the subject and the presentation, and that distance allows everyone to contemplate potentially divisive or explosive topics from a remove. Maybe you can’t change minds by tricking them, but it’s a start, and it’s better than staying silent, right?

Sometimes, though, a metaphor isn’t enough. Sometimes you need to scream—not talk about screaming, not have someone scream in some different, made-up language that nerds will obsess over for years to come; not couch a scream in diffidence or bury it in poetry. Just scream. Maybe then, someone will hear you.

Star Trek has a long history of using science fiction tropes to deal with social issues. We did a semi-jokey Inventory on the subject four years ago, and it’s always been a symbol of the franchise’s noblest aims—to be more than just an adventure show, to have ambition beyond nifty monsters and star fields. But as admirable as that aim is, it’s too often a clunky, heavy-handed way to moralize. Check that Inventory more closely, and you’ll realize that while most of those episodes (and films) are fun, few of them rank in any of their respective series’ best. Using a metaphor to tackle a controversial issue is an approach that reeks of putting message before story, which can easily turn into an excuse to lecture an audience; after all, most messages come with a specific moral value attached, which means there’s little room for ambiguity or mystery. Force-feeding is rarely an effective means of storytelling or lesson teaching. At the time, it lets everyone pat themselves on the back for being progressive and clever; decades later, it looks pedantic, trite, and more than a little campy.

This isn’t always the case. Star Trek: The Next Generation managed to do issue episodes better than the original series, and some of its attempts are very strong stuff. But even then, the metaphor works best when it deals in broad terms. “Darmok” is a fascinating examination of the difficulties of communication between cultures, and the challenge of finding common ground. You could apply it to any number of disastrous encounters between different races of humankind, but there’s no need to. The fundamental truth transcends the specific. Something like “The Outcast,” which has Riker falling for an androgynous alien from a society where gender distinctions are harshly censured, succeeds, in part, because its soul isn’t just about the persecution of the homosexual or the transgendered. If you want to, you can take a powerful statement on the importance of tolerance and respect for all sexual orientations from the episode. But you can also look on it as a critique of totalitarian governments. Or just a tragedy about Riker losing a friend. By tapping into the universal concepts underlying specific cultural problems, TNG was able to get their point across without being anchored to one view. It’s a potent use of metaphor, and yet there’s a distance to it. The separation between our world and the ones we see on screen means that commentary comes at a remove. The remove makes the criticism easier to take, but it also diminishes its impact. This isn’t personal, the metaphor allows us to believe. We’re only observing. We’re not a part of this.

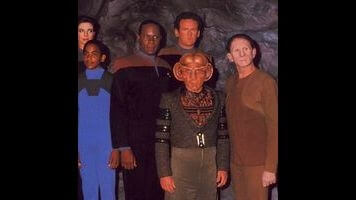

“Far Beyond The Stars” takes the metaphor and turns it inside out. It is not a subtle hour of television. It has its gimmicks, but the gimmicks are in no way relative to its effect. The double-casting—seeing familiar faces in different roles, seeing actors out of make-up, seeing Michael Dorn smiling—is fun to watch, but there’s something sad about it, too; something lost and awkward and lonely. This is not an episode which holds back. There is no happy ending for its hero. Instead of using the illusions of fiction to cloak or obscure painful realities, writer Benny Russell (Avery Brooks) attempts transcendence. There is no comforting distance between us and his situation, no camouflage for his pain. Even the time (Benny is in 1953 America) isn’t all that far away. There is no protection for an audience eager to cling to its illusions. This is a desperate man’s effort to cling to sanity, to speak and be heard in a place which demands his silence. The metaphor is not there to teach us a lesson about the suffering. The metaphor is there so that the suffering might rise above.

In case the four paragraph preamble to a point didn’t tip you off, I’m not entirely sure how to approach this one. It’s exceptional in a way that makes me nervous about dissection or critique. I’m used to writing silly things about reversed polarity and Cardassians and what not. Racial injustice is not something I feel qualified to discuss. I can’t quote you specifics on the struggles of African American pulp fiction writers from the 1950s, nor can I offer a personal anecdote in any way relevant to the matter at hand. To do the latter would be obscene; not because the episode is some holy, sacred object (I liked it a lot, and it’s grown on me since watching it, but it’s kind of crazy and clunky at times, sort of like this review), but because I, in my limited experience, cannot speak to Benny’s plight. When it’s Sisko, or Bashir, or Odo, or Kira—I get that. That’s easy. But actual systematic prejudice? I’ve had the biological and geographical luck to have been spared such a thing, and while I can empathize (great art makes empathy easier), I'm also reluctant to speak with any kind of authority on the subject.

Part of the value, then, of an hour like this (and yeah, it’s not all set in the past, and the way the script and Avery Brooks’ direction chooses to integrate the “reality” of the show with the “reality” of Benny’s world is quite striking) is by presenting a different perspective from the sort that usually gets center stage in popular entertainment. It’s true that Brooks is the first black lead of a Trek series, and it’s true that Deep Space Nine (much to its credit) has never tried to downplay or ignore this. Yet DS9 takes place in a comparatively utopian future. It’s a more pessimistic show than TNG, but that pessimism doesn’t take away from the fact that the Federation—the dominant “good guy” force—doesn’t discriminate based on race or, one would hope, gender or sexual preference. To the audience, Sisko’s blackness is an important step forward for the franchise, indicating a broader acceptance of non-white protagonists. In the context of the show, though, it’s just another part of who he is; it matters, but it doesn’t define him in the eyes of those around him. There’s something refreshing about that, of the fantasy of a future which has so many different kinds of people (human and otherwise) that you’re too busy trying to keep up to hate any of them. (Unless you’re a Cardassian. Things are pretty easy then.)

At the same time, though, there’s a lie in that fantasy, the same lie people tell themselves when they talk about “post-racial” America. The future is a lovely place to imagine, but we don’t live there, and in the present, things are more complicated, more frustrating, and quite often more awful. Today, diversity in television and film remains a pressing issue, because by clinging to narrow definitions of “protagonist”—by insisting that audiences are ready to see onl certain genders or ethnicities in certain roles—we are robbed of the width and breadth of experience that fiction is supposed to provide. Worse, many of us are robbed of a voice in that fiction. So the simple fact that “Far Beyond The Stars” tells a black story with a black hero and his black girlfriend and their black friends means something. What happens to Benny has, like “The Outcast,” resonance that goes beyond one person’s pain, but no matter how deep or far you go, Benny is still standing at the heart of it. It’s telling, and upsetting, to realize that it’s still unusual to see even an hour of television which doesn’t give us a white audience surrogate, that doesn’t have some square-jawed Caucasian strolling into a situation, taking its measure, and saving the day. There are white folks in “Far Beyond The Stars,” and some of them are quite nice, but even the nicest of them is fundamentally ineffectual. They can apologize, they can sympathize, they can even protest, but that’s as far as it goes. Benny tries and he fails, and even when the metaphysics take over, they can’t deny that simple fact. Anyone who’s watched enough TV has seen a story about a black man or woman being told what they can and can’t do, but for once, there’s no outsider standing to the side, shaking his head sadly. There’s just Benny and us.

That’s wrenching to watch. Strip away the sci-fi elements, and this is a straightforward tail of prejudice, with barely enough meat on the bones to carry it through an entire hour. Benny wants to write stories about a black captain; his editor, Douglas Pabst (Rene Auberjonois, who looks older than I was expecting), refuses to publish those stories because he doesn’t think the public is ready for them. They come up with a compromise—the stories will all turn out to be “dreams”—but the owner of the magazine pulps the issue, refusing to accept Benny’s work. Benny loses his job and collapses. He isn’t beaten to death (although his friend Jimmy, played by an amusingly unconvincing Cirroc Lofton, is shot and killed by the cops) or framed for a crime he didn’t commit. He just loses a chance to do what was most important to him, for no better reason than bigoted stupidity. Brooks spends most of his time as Benny playing it quieter than we’re used to seeing him. This is a man who keeps his head down, and then one day he raises it, and suffers for the effort. Benny’s big monologue is half-crazed poetry, the sort of broken heart madness that Brooks is so good at. He risks absurdity, but it’s earned. The hour manages its racism casually and oppressively, like getting the color of the paint on the walls right. Even Jimmy’s death is just something that happens, with no surprise at all. When the hero finally breaks under the pressure, it snaps the scene into focus. These aren’t just indignities. This is a constant battery of mental and physical abuse.

Brooks’ performance dominates the episode, which is for the best; the rest of the cast turns in work that’s varying degrees of successful. (Anyone wanting to get a clearer sense of everyone’s relative abilities would do well to watch this; apart from Brooks, I think Auberjonois, Penny Johnson, and Armin Shimerman come out the best). But even in the worst performances, there’s enough of a sense of the actor, and of the character we’re used to seeing them play, that it works. As for the metaphysics, well, it has its moments. Sisko’s transition from being stressed over his job and worried about the future to seeing visions of Benny and his world is defiantly odd, refusing to offer a simple, easy explanation for what’s happening. It’s not just a hallucination; Bashir determines Sisko’s neural patterns are spiking or whatever, much the same way they were spiking or whatever back when Sisko was getting visions from the Prophets. You could say, then, that this is the underlying truth of the entire series—it’s all just Benny’s fantasy—and I won’t say you’re wrong. But I’m not sure Benny’s world is ever solid enough to make that qualification mean anything. What we see is defined enough to make this episode work, but it doesn’t have the history or the breadth of the series as a whole to make the “It’s all in a writer’s head!” argument more than just a fun thing to speculate on in comment threads.

In terms of the character doubling, some choices are obvious: Dukat and Weyoun as asshole cops isn’t a huge surprise, and even though Cassie doesn’t have the same ambitions Kasidy does (for understandable reasons), her relationship with Benny is as strong as Kassidy’s is with Sisko. Other connections are subtler, like, say, O’Brien turned into the Isaac Asimov stand-in Albert Macklin, who loves machines much like an engineer would. Jimmy isn’t exactly like Jake (Lofton’s performance is endearingly forced, and he is, I think, the only actor to ever say the n-word on a Trek show), but his relationship with Benny is of the sort where you can imagine the writer trying to come up with something better for both of them, a situation in which the older man can impart some much needed knowledge to the younger. Seeing Odo as Pabst might be the coldest cut of all, as Pabst’s placating approach to his work is similar to Odo’s behavior during the Cardassian occupation: a shape-shifter who only chooses the form that will please his masters.

Yet Odo, our Odo, rose above this, and if you accept, for a moment, that Benny really did write everything we’ve been watching over the last six seasons, there’s something beautiful in how he tried to find ways to turn ordinary people into heroes. The writing staff at the magazine became a brave crew with complicated histories and passions; more, they became a family, one in which Sisko is first among equals. Cassie got a ship and adventure. Willie Hawkins, the lady loving baseball player became a warrior (a somewhat humorless and stiff-necked warrior, but when a guy keeps hitting on your girl like that, you gotta take revenge where you can find it). The asshole cops get justice as villains who will, in the end, be defeated. And Benny? Benny gets a space station and a loving father and a loving son. He gets the respect of his peers and the voice of the gods.

A metaphor—a secret lesson, a code to slip past the guardians of culture—that can do some good. It can be necessary, and useful, and just. But a metaphor can also be all that you have left. It can be a way out. A way free. "Far Beyond The Stars" succeeds because it does have universal concerns: the desire for respect, to be free to aspire without constraint. But by refusing to cloak those concerns in pure symbol, by reminding us that these things do happen, are, in fact, still happening every day, the episode escapes the trap of message and commentary and creates something unique. Maybe somewhere, Benny Russell is dreaming. And maybe someday, he won’t need those dreams.

Next week: We return to our regularly scheduled programming with a double shot of “One Little Ship” and “Honor Among Thieves.”