Star Trek: "Requiem For Methuselah"/"Way To Eden"

I wouldn't mind living forever. Despite all those Twilight Zone episodes about the dreariness of immortality, I, personally, would be willing to take the risk of boredom and despair ten thousand years down the line, if that meant not having to be dead. I imagine most people would. Generally, fiction that deals with excessively long life tries to convince us that this is the wrong choice. You have the occasional pro-immortality piece (I always thought Neil Gaiman had the right idea of it in Sandman: no major revelations, just existence prolonged with all its minor triumphs and loss), but mostly, writers are heavily invested in convincing us that death is natural and therefore desirable. Maybe undertakers have a very strong lobby, I dunno, but "natural" to my way of thinking doesn't invariably mean "necessary."

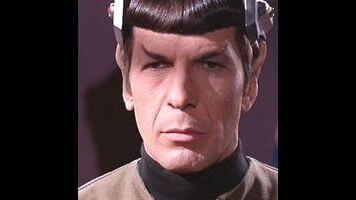

"Requiem For Methuselah" would disagree with this. Well, all right, it's a fifty minute episode of a forty years gone television show, it doesn't really get much in the way of active verb sentences. But the seemingly immortal Flint has definitely developed some issues as a result of being kept long past his expiration date. He bought a planet (I love how casually this is mentioned, as if buying planets that could support life were the sort of thing you'd expect from any reasonably well-off gentleman) just so he could avoid the company of others, and when Kirk, Spock, and McCoy beam down, he's not very happy about the surprise visit. The Enterprise has caught a bad case of Rigelian fever, and they're short on ryetalyn, the only known cure. Thankfully, Flint's planet is loaded with the stuff, and after some very heated debating, he gives in to their demands and offers to send his robot probe, M-4, to collect the plague-stopping chemical while the others come back to Flint's place and, y'know, hang out and stuff.

For an apparent hermit with no recorded history, Flint's amassed an impressive art collection, from a series of unknown Da Vinci's painted on modern canvases with modern materials, to a new Brahms' waltz written in fresh ink. But the jewel of his collection is a young woman named Rayna. Cultured, beautiful, intelligent, and charmingly naive, Rayna makes an immediate impression Kirk, and she on him. So, while the rest of his crew on the ship is battling sickness and waiting desperately for a cure, Kirk starts seducing the ward of his barely tolerant host. Spock's getting suspicious, though. What's with all the fresh/old art? And his suspicions are confirmed when McCoy's sensor reading on Flint reveals Flint to be somewhere in the area of really, really old.

There was discussion last week about my "soft" grading for this season of Trek, and I won't deny that. I'm not trying to create some kind of textbook perfect scale here. Unless an episode is particularly horrible or particularly good, I'm more interested in working out the oddities and making cheap jokes. I start each ep assuming it's in the B/B+ area, and then adjust accordingly. So "Requiem" started off okay for me. There's a certain level of improbability you have to swallow here, that the Enterprise would get hit by a virus that gives them a very specific timetable to survive, and that the only cure for that virus would be found in substantial quantities on a nearby planet that just happens to have a human immortal who just happened to have been born on Earth. A less charitable person than myself would also point out that the Rigelian subplot is the worst kind of MacGuffin, one that seems deathly important when first introduced but becomes arbitrary and perfunctory as soon as is deemed narratively convenient.

I'm willing to look past that, though, especially in the third season. But "Requiem" kept disrespecting my goodwill. Again we have an episode where the audience is always a few steps ahead of the cast, and those few times it did manage to surprise me where more ridiculous than thrilling. That Flint just happens to have been Leonard Da Vinci and Brahms and a bunch of other famous guys is absurd, and needless, especially considering his explanation about how he had to learn quickly to not let his "special" nature become public. Right, so you live forever, and the best way to conceal that is to keep being insanely famous and influential. Some super genius. Also, for someone who's spent such a terribly long time watching people be people, he doesn't really understand humans very well. (Tip: Ordering someone who doesn't like you like that to stop caring for another man will never work out in your favor.)

Not to mention the ridiculously blase explanation for his immortality—apparently, he's just really good at healing. That's it. I'm a little torn on this one, because it's so bald-faced and unconcerned that I kind of like it. When there's no possible reasonable explanation for a situation, bluffing can work as well in fiction as it can in poker, depending on how straight-faced it's delivered. That neither Kirk, McCoy, nor Spock question this discovery goes a long way towards making it work. Still, it seems like a lost opportunity for something more clever than "I was born this way." (Admittedly, the episode justifies Flint's extraordinary abilities as a result of his longevity, but I'm not sure I'm buying. Bill Murray was a pretty great piano player after all those Groundhog Day lessons, but he wasn't a master composer just because he had a lot more time on his hands.)

What really killed "Requiem" for me, apart from Flint's inconsistencies and the story's familiar Forbidden Planet parallels, was how much it had to betray Kirk's essential nature in order to justify its story. We've seen Kirk falling for beautiful women, and them falling for him in turn. You can make jokes about it, but it's an established element of the show's mythology. But here, we're supposed to believe that Kirk is so instantly and irrevocably smitten with Rayna (an android Flint built to be the perfect woman) that he's willing to put his ship and the lives of everyone aboard at risk. Despite Spock's repeated warnings, Kirk flirts with Rayna, pursues her, and then demands she leave with them, because he can't bear to see how Flint treats her. He's known this girl less than four hours, and he's so blinded by love (to put it charitably) that he loses the sense of duty that has been his strongest single characteristic since the first episode? I'm not buying that.

And it's too bad, because as others have noted, the final scene could've been moving if it had had a stronger foundation to rest on. Spock uses his mental powers to erase Kirk's memory of Rayna, sort of a one-time only Lacuna, Inc. treatment. It's a beautiful idea—Spock's outsider status doesn't just mean making snappy comments and having to clean up after the stupidity of his co-workers, it also gives him the responsibility of total observation, of holding onto memories that others would rather let go. McCoy lectures him on his inability to feel love, but that final gesture is definitive proof otherwise. (As if we needed it.) Were it not for the absurdity of Kirk's grief, this could've been a series highlight. Instead, it's a brief blip in an otherwise forgettable ep.

Still, forgettable isn't necessarily the worst thing. At least there aren't any space hippies. "The Way To Eden" is one of the notorious season three episodes that's hard to view straight, partly because it's been a punch-line for Trek fans for years, and partly because SPACE HIPPIES. It's gets ugly when popular culture tries to address a sub-culture it doesn't entirely understand. Regular hippies can be annoying enough, but the goofy nutjobs we see here are like a photocopy of a parody of an idea. A really tedious idea that keeps singing. Oh man. I was doing okay until the songs started happening. That about killed me.

"Eden"'s premise should be familiar to anyone who's seen Star Trek V. (Yeah, seriously, if that doesn't give you a chill, you are made of stone. Or else you haven't actually seen Star Trek V, which means you are made of something significantly smarter than stone.) A small cult of true believers gets on the Enterprise—Kirk has to treat them well because one of them is the son of an ambassador—and that cult is determined to use the ship to help them on their quest. They're disillusioned with modern life, with all its computers and sterility and insistence on bathing, and they're trying to find their way back to where it all started, the very first planet, Eden.

Given how generally perfect the future of Star Trek seems to be, I will give "Eden" this much: it gives us a dissenting voice in Utopia. That that voice comes out from the touring cast of Hair damages its credibility somewhat, but the fact that Spock adds his support is hard to ignore. Spock has always been the sanest person on the ship, and to have him come out in favor of a bunch of trippy sland spouting airheads creates an odd dramatic tension. We see Dr. Sevrin and his motley band of morons babbling along, and then we hear Spock calmly defending their cause, and suddenyl, you've got to take the dolts seriously. Obviously they have problems, and their dress sense could use some work (but then, it's not like freaky costumes are a rarity on the show), but maybe there's something to their yearning for a new beginning, a freer, purer home. Maybe they aren't just a group of spoiled morons who use the pretense of idealism in order to distract from their essential wounded selfishness.

Still, there is all that singing. (From character actor Charles Napier! Playing an instrument that in no way could make the sounds it's supposed to be making.) While I appreciate the contrast between the space hippies appearance and Spock's calm, rational assessment of their goal, the group is too strange and irritating for me to view them sympathetically. Kirk is stuck as the straight man for once, as none of the hippie girls fall for him, and as funny as it is to hear people call him Herbert, we're firmly in Kirk's corner. Plus, even Spock admits that Sevrin is insane. He's a carrier of a virus that could kill the perfect world he yearns for, and he refuses to accept this. Kirk throws him in the brig, but the hippies spring into action, distracting and seducing the crew, and ultimately stealing the Enterprise so they can find their way to their precious destination.

The crew seduction never goes anywhere; even Chekov is able to resist his old girlfriend's advances. Sevrin has to knock everybody out with a sonic device that should be fatal, only Kirk is just too badass to die. It's all a set-up for one of other parts of "Eden" I honestly liked: the hippies steal a shuttlecraft to visit their new home, and it nearly kills them. All the vegetation is poisonous and highly acidic. Nothing can be touched, nothing can be eaten. Spock tells the surviving cultists that he hopes they continue their search, but I like to think that this place really was Eden, and that when God kicked Adam and Eve out the door, He made damn sure they wouldn't be able to sneak back in.

Really, I would've been a lot more patient with this one if it weren't for the songs. The action stops cold every time Napier picks up his whatever-the-hell-it-is and starts warbling. I think Sevrin's quest is foolishly naive, and the condescending emptiness of his followers is nearly intolerable, but at least those have something to do with a story. At least all the "Herbert" crap has a point. The singing is just the worst kind of padding, and it burns more than a few Edenic bushes ever could.

Grades:

"Requiem For Methuselah": C

"The Way To Eden": C-

Stray Observations:

- "That's now, that's the real now!" Ahh, it's like poetry.

- I did like the explanation that Flint was already dying when Kirk and the others met him. It explains why he looked fairly old for somebody with perfect cellular regeneration.

- Irina tells Chekov, "Be incorrect… occasionally." Oh sister, he is way, way ahead of you.

- So, how about you—you wanna live forever?

- Next week, it's "The Cloud Minders" and "The Savage Curtain"