Star Trek: "Shore Leave" / "The Galileo Seven"

I used to love the holodeck. The episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation that focused on it were always my favorites; just the idea of some magical machine that let you play around in whatever fictional environment suited your fancy seemed, to my ten year-old mind, unbelievably exciting. It still kind of does. But the more you think about the concept, the more absurd it becomes. I mean, considering the number of times the 'deck malfunctioned, surely it would've been easier just to shut down completely. Every other week the safety protocols broke down, or an AI was inadvertently created capable of taking over the entire ship, or somebody would stumble across the creepy wish-fulfillment fantasies of another crew-member and things would get—awkward. (I'm looking at you, Barclay.) Picard always managed to set things right somehow, but given the number of ships in the Federation, I'm willing to bet not everyone was so lucky. ("Hmmm. There's been some racial tension between the Vulcans and the Ferengi lately. I know, we'll recreate Hitler to teach everyone a valuable lesson about prejudice. What could possibly go wrong?")

Still, it's a nifty idea. And as "Shore Leave" proves, in isolation, it can make for a mighty entertaining episode. Sure, the subtext is a little creepy, and common sense raises all sorts of questions as to just what the hell is going on, but if we were heavily invested in common sense, we wouldn't be watching a series about a paramilitary organization that dresses all of its female officers in minis and matching bikini bottoms.

Speaking of which, new Yeoman this week! Rand must be off getting her hair done (takes space-weavers a full week to get it set properly); standing in for her is a brunette by the name of Barrows. She gives out drinks and back-rubs like a pro, which is a lucky thing for Kirk. He's been feeling the strain of command lately, and in truth, everyone on the ship (apart from Mr. Spock) is stressed and in the need some good old fashioned R & R. Thankfully the Enterprise just happens to be orbiting around a new planet with a human-friendly atmosphere, gorgeous plant life, and no tricky animal life to harsh anyone's buzz. McCoy and Sulu are doing a quick survey, and both men are absolutely delighted at what they've found. It's like Heaven minus the snakes, and just what the good doctor ordered. Sulu wanders off to get some clippings from the local flora, and that's when a giant white rabbit shows up. McCoy does a goofy double take, the rabbit does a familiar "I'm late!" routine, then bounds off; seconds later, a little blond girl the spitting image of Lewis Carroll's Alice passes by. Things have just gotten weird.

"Leave" operates like a short story; one excellent twist aside, it's all first act until the final reveal. We follow a handful of characters down on the planet (McCoy, Sulu, Kirk, Barrows, and new faces Rodriguez and Angela) as each of them is charmed or menaced by something bizarrely familiar that couldn't possibly be what it looks like. Each character wonders what the hell is going on, but is either so overcome by the mystery or by the immediate danger that mystery puts them in, that they fail to recognize the obvious connection: whenever anyone thinks about a person or thing for too long, that person or thing immediately appears in front of them. (Thankfully, nobody thinks of J. Edgar Hoover or Mr. Stay Puft.)

And the things these people think up! Beyond McCoy's fondness for the classics, we've got Sulu manifesting a yen for old school fire-arms and samurai. (Given that the gun comes first, it would've made more sense if he'd been thinking about cowboys or cops, but whatever.) We've got Rodriguez thinking about tigers and fighter planes from World War II. We've got Kirk remembering the sonofabitch who used to torment him back at the academy, as well as an eerily baby-faced lost love named Ruth. And we've got poor Barrows conjuring up Don Juan, who immediately tries to rape her. Kirk's fantasies are essentially harmless (Finnegan's annoying, but the epic fist fight they get into is more cathartic than painful), but that's some dark shit from the rest of the group. The assault on Barrows alone is nasty enough even before McCoy gets a lance through the chest; given what we ultimately learn about the planet and the purpose it serves, you have to wonder just how much truly dark shit used to go down when the place was doing peak business.

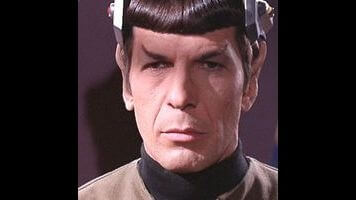

But yeah, about McCoy getting killed—that's a shocker, no question, and it does a great job of breaking up the episode's somewhat repetitive structure. While the various fantasies we see play out are imaginative enough, it's gets tedious watching what's essentially the same thing happen over and over again, especially since it's hard to imagine anyone not figuring out the twist these days. The crew-members inability to reach the logical connection between thought and manifestation is pretty hilarious. (Of course Spock gets it immediately, but then, that's kind of his thing.) McCoy's death makes everything seem much more serious. That it's shrugged off at the end with no more explanation than a punchline is too bad, but hey, it's not like they were really going to kill him.

Once Kirk beats the tar out of his feelings of inadequacy and Spock puts the pieces together, it's a simply matter of blanking everyone's mind to flush the ringleader of the afternoon's events out into the open; a kindly white-haired gentleman who tells our heroes that a.) this is all for fun, didn't you know that and b.) you're not ready to know who we are or how we do what we do, which saves the writer having to actually explain anything beyond the standard "Aliens can do anything!" line. McCoy is returned good as new, along with Angela, who earlier got shot by a passing plane (serves her right, really; her fiancee barely in the space-ground and she's already got a new beau), and everybody has a hearty laugh about everything. Spock returns to the ship (I love the little bit he does with the cabaret girl who attaches herself to his arm), and Kirk orders the landing parties to start beaming down so everybody can have a gay old time. But, as is so often the case with TOS, certain questions remain. Like, just how psychologically healthy is it to spend your time with a phantom simulacrum of an old lover? And stranger still, if the beings who run this planet have equipment sophisticated enough to read what a person is thinking about, why did it take them so long to realize that the Enterprise crew wasn't in on the joke? Either somebody was asleep at the wheel (maybe the staff were all in stasis?) or—and here's my theory—they were just bored as hell, and decided to fuck with the idiot humans to pass the time.

Whatever the motives, "Leave" is a lot of fun, campy enough that you can overlook some of the sillier plot elements, and with a strong hook to keep the camp from descending into self-parody. "The Galileo Seven" has got nearly as strong a hook, but I'm sure I'd use the word "camp" to describe it; I definitely wouldn't use the word "fun." This one's a mixed bag, and I'm not sure how much of that is flawed writing, and how much is just me really not seeing Spock proven wrong. "Seven" comes dangerously close to one of my least favorite thematic debates, the "Head or Heart?" conundrum. There's nothing inherently wrong with the question itself; as human beings, trying to figure out how much emotion and how much logic to apply to any given situation is something we have to struggle with our whole lives. What gets on my nerves is that nearly every time the issue gets raised in pop culture, we're always supposed to come down on the soppy side of things. Whenever a character approaches a problem with their intellect, nine times out of ten the lesson we learn is, the more you think, the less you know.

"Seven" starts out promisingly enough, with Enterprise coming across the Murasaki 312 anomaly, a giant floating green cloud in space that causes havoc with the ship's instruments and represents a tremendous opportunity for study. While currently tasked with delivering life-saving medicine to a colony hit hard by the plague, Kirk is willing to spare a few hours time to follow his standing order of scientific exploration; we're supposed to think this is reasonable, as the only person who thinks it's unreasonable is Galactic High Commissioner Ferris, who just happens to be a complete dick. When it comes to medicine that can stop a plague, one would think that speed be the first thing on everyone's mind, but I guess the timing is different with space plagues. Anyway, Kirk makes the call, so I can dig it.

Spock goes out to take a look around in the Galileo, one of the Enterprise's shuttlecraft; he brings McCoy, Scotty, and a few random crew-members along for the ride. McCoy and Scotty seem like odd choices, in much the same way that Kirk's insistence on beaming down when there's even a hint of trouble to be found does. It's possible that a medic and an engineer could come in handy on a scientific expedition, but surely Scotty at least has subordinates he could send along? When the shuttlecraft goes missing, we spend part of the episode watching Ferris begrudge Kirk the time he spends searching for it, but since his First Officer, Head Doctor, and Chief Engineer were all aboard at the time of the disappearance, Kirk doesn't really have a choice.

The Murasaki effect ruins everyone's day, forcing the Galileo into a crash-landing on the nearest planet, and effectively stranding the seven people inside. (Just like the title! Clever.) Spock, being the highest ranking officer around, takes command, and trouble starts almost immediately. See, Spock is logical, and that means he's cold and heartless and generally not a very likable guy. McCoy has been riding him for as long as the show's been on, and for once he's not alone; most of the seven spend the episode split between shock at Spock's supposed heartlessness, and enraged at same. Scotty determines there's been a serious power drain of the ship's energy reserves, and it'll take some doing to get them back into space; specifically, it'll take the loss of 500 pounds. This leads to a discussion about who gets left behind, with Spock saying he'll make the most "logical" choices, and McCoy and Lieutenant Boma not being particularly happy with the assertion.

While Scotty fiddles with the engines, Spock sends two spare crewman, Latimer and Gaetano, out to stand guard. This resultd in Latimer getting a gigantic spear through the back, confirming for everyone on the Galileo that they are not alone, and that the inhabitants of this particular chunk of rock are apparently giant, supremely pissed off cave-man. (Of all the places to crash on, they have to hit the Planet of the Eegahs? Hope they keep an eye out for snakes.) Here's where the battle between intellect and instinct really gets going, as the crew is urging for an immediate retaliatory attack on the Eegahs, while Spock, who abhors unnecessary loss of life, would rather figure out an approach that didn't result in more death. Since Spock is in charge, he makes the final call; he, Boma, and Gaetano take a quick trip into enemy territory, lay down a brief phaser light show, and then skedaddle back to the shuttlecraft. To Spock's mind, this will frighten the cavemen off, and give Scotty the time he needs to finish his work.

Thankfully, Scotty has come up with a plan—by draining the energy out of the crew's hand phasers, he can give the Galileo just enough fuel to get back into orbit and hopefully attract the Enterprise's attention. At this point, Kirk could use the help; despite his increasingly desperate (and largely futile) search efforts, he hasn't made any progress, and Ferris continues to remind him of his obligations elsewhere. The somewhat arbitrary deadline here gives us some suspense, but like so much of the episode, it's pretty unpleasant to watch. Ferris himself is remarkably unsympathetic; while his desire to get medicine to the sick is laudable, his insistence that Kirk desert his men is, well, dick. Mostly it's just the way the actor plays it—the guy actually smirks when the Galileo goes missing.

That dickishness is my biggest problem with "Seven," because it's not just restricted to the bridge of the Enterprise. The debates that Spock, Boma, and McCoy engage in are rough going, regardless of their philosophical implications, and seeing Spock turn out to be wrong—his "logical" approach to the caveman problem winds up getting Gaetano killed—makes Boma's seething fury a lot harder to ignore. Spock's utter bafflement at his failure doesn't make much sense, either. He's been doing what he does for over a decade at this point, surely he would've realized by now that people don't always behave logically? Using your brains to work through a problem doesn't mean assuming everybody else thinks exactly like you. (Although given Spock's repeated astonishment at nearly every human emotional response, maybe this is just a blind spot for him.)

Of course, the humans don't come off all that swell either. In addition to his obvious resentment of Spock, Boma also has the genius idea of having funerals for not one but both of the dead crewmen. I can sympathize with his desire to put Latimer in the ground; despite the recent discovery of nearby hostiles, Latimer's death happened far enough away from the Galileo that holding a brief service could be considered at least somewhat safe. Of course, that's not taking into account the necessity of speed in the shuttlecraft repairs, but Boma doesn't seem to be helping much there anyway. The really stupid bit comes when Gaetano dies, and Boma wants to bury him too. At this point, you've got the giant cavemen coming at you full bore (well, "giant" seems somewhat relative here); having everybody stand around outside just to mouth a few words to a corpse that's well past the point of hearing them is both selfish and stupid. Even worse, Boma is up in arms when Spock points out this obvious fact.

In the end, though, it's Spock's rationality that takes the hardest hits. In addition to his screw-up with the initial attack, he also orders the rest of the crew to leave when he gets pinned under a boulder during the Eegahs' last assault. On the one hand, this proves he's committed to his beliefs; on the other, it shows how the humans, who put their feelings above their common sense, are willing to risk themselves and save his life without losing anyone else. (Spock's "Go on without me!" looks particularly foolish given that he's no more than five feet away when he starts yelling it.) And the ultimately coup de grace comes when the Galileo rises into space and Spock chooses to jettison and ignite their remaining fuel as a last ditch attempt to get the Enterprise's attention. It's a desperate move, and, according to McCoy, a "human" one; something which the bridge crew is all too willing to rub in the half-Vulcan's face once everyone is back home safe. (Nice to see they all got over the deaths of Latimer and Gaetano so quickly.) "Seven" raises some interesting issues, but the fight comes off as fixed from the outset; and there's not a lot of thrill in watching a fixed fight.

Grades:

"Shore Leave": A-

"Galileo Seven": B

Stray Observations:

- "I, for one, do not believe in angels." Oh, but Mr. Spock, they believe in you.

- Barrows wants to be a fairy tale princess, McCoy wants to make time with hottie cabaret chicks, and Sulu likes samurai. Too bad Riley didn't beam down, we could've had Warwick Davis go apeshit on everybody.

- The mannequin inside the Black Knight armor that kills McCoy is really, really freaky looking.

- Next week, the Enterprise battles Liberace and the Gorn in "The Squire Of Gothos" and "Arena."