Star Trek: The Next Generation: "Unnatural Selection"/"Matter Of Honor"/"The Measure Of A Man"

"Unnatural Selection"

How do you solve a problem like Pulaski? Let's overlook the character flaws, the miscasting, the way she doesn't quite fit, and just deal with generalities. As mediocre as the first season of TNG was, the new crew of the Enterprise was a solid unit by the end. Some of them had been developed better than others, but with the death of Tasha Yar, we finally settled into something approaching a groove. People had roles, and they fulfilled them, and even more importantly, those roles all meshed with each other reasonably well. Yes, Troi was a bit on the useless side ("I sense understatement, Captain,"), but this is less about individual importance and more how we, as the audience, became attached to a certain concept of the show's cast. You watch something long enough, you develop a bond with the people you're watching. Upset that bond, and the show risks ruining one of the few undeniable advantages it has.

Enter Pulaski, then. It's the second season, so it's not automatically the end of the world to do some cast change-up. Beverly Crusher, while pleasant enough, hadn't had a huge amount of character development (dead husband, nerdy son, had the hots for Picard), so her absence doesn't ruin any delicate structures. The trick, then, is trying to make her as important to the audience as the rest of the crew, in a much shorter span of time. The downside is, before Pulaski is sufficiently developed, her sudden appearance can throw off the cast chemistry, her scenes becoming dead spots in each episode. Fortunately, though, since the rest of the character know their responsibilities, it's easier to contrast their personalities against this new person's, and use that contrast to flesh her out.

Well, that's a theory, anyway, and "Unnatural Selection" is an attempt to do something with that theory, by giving Pulaski her first real main storyline. Not only is she the person driving the action for much of the episode, characters spend an awful lot of time discussing her in her absence. By the end, we have a much clearer picture of the character—or at least, we have a clearer picture of what the writers really want her character to be. Unfortunately, like I mentioned at the start of the season, those intentions fail to live up to the final result, and what we have is a classic example of a strong actor unable to find a necessary sympathy with the role she's performing.

The Enterprise gets a distress signal from the Lantree, but by the time they arrive the entire crew is dead of old age. (Pulaski does a scan, brings out the old chestnut they always deliver in premature seniority story-lines: "They all died of natural causes." Why is this supposed to be more shocking than the evident fact of their advanced aging?) We get a neat scene where Picard takes remote control of the Lantree via computer codes, just like Kirk took control of Khan's ship way back in Wrath Of Khan, and then a quick scan of the records determines that the ship's last stopping point was at the Darwin Station. They do genetic research there. Wonder if that's relevant?

The crux of the episode is Pulaski's supposed humanism. As a McCoy analog, she is supposed to be passionate, willful, and intent on putting her patients' needs above all other concerns. In practice, this means becoming immediately and deeply obsessed with protecting the results of the research done on Darwin: supposedly genetically perfect humanoids who are unaffected by whatever's causing the aging sickness. The Darwin scientists themselves are all suffering, including their spokeswoman, Dr. Kingsley, who blames contact with the Lantree for the problem. She demands that the Enterprise beam the children aboard, since they won't be able to fend for themselves with the adults dead. Pulaski agrees with Kingsley's assessment, despite never having seen these children, and despite the fact that contact with them would put the Enterprise's crew—people it's her job to protect—in potential danger, regardless of Kingsley's repeated assurances otherwise.

Pulaski's commitment to a foolhardy idea doesn't do her any favors. Over and over throughout the episode we're informed of her devotion, her stubbornness, her intellect, and while all three traits are technically apparent, in practice, they don't serve to make her more endearing. Her arguments with Picard don't work, because it's impossible to understand what point she's trying to make. Intellectually, yes, a case could be made for the importance of protecting the kids, given the amount of time and research put into them, and simply for their rights as living, sentient beings. In order to make that case work, though, a person would have to be so convinced of the rightness of their cause that their passion for it would overwhelm all other responsibilities. It would need to be a situation in which the children will die without immediate intervention.

This sort of conflict happened all the time in TOS. Kirk was often faced with situations in which he'd need to sacrifice the few for the needs of the many, and part of McCoy's job on the show was to make sure the voice of those few was always heard. The trouble is, TNG doesn't really deal in the same levels of danger. There have been (and will be) times when the crew is in incredible peril, but rarely are we faced with the kind of moral dilemma that the original show did so well. If TOS was about translating fables into science fiction, TNG is about using science to exhaust all options. There's no sense of necessity in Pulaski's demands. She comes off as short-sighted and immature, and given that her entire performance is so restrained and detached, there's no way to empathize with her.

Really, Diana Muldaur isn't right for this part. Her sudden intense desire to protect the kids comes across less as a defining characteristic than as a weird kind of nervous breakdown. We learn over the course of the episode that Pulaski is frustrated with Picard's "by-the-book" methods, which is a conflict I had to keep reminding myself had been established before (she objected to the security team being present while Troi gave birth in "The Child"), and then later we discover she specifically requested a transfer to the Enterprise because of her deep respect for the man. Neither the conflict nor the respect rings true. Pulaski seems to equally dislike everyone on the ship, and if she's so in awe of Picard—a man who's methods she's studied, a man who she herself has accused of being obsessed with regulation—why the hell would her first act upon transferring aboard his ship be to ignore him and directly contradict established procedure?

Pulaski gets her way, and deals with one of the kids, putting herself and Data at risk in order to prove what anyone with a brain knew ages ago: the kids are responsible for the aging sickness. Super genius Kingsley keeps bragging about the children's perfect immune systems, and it turns out those immune systems are so amazing that they produce airborne antibodies at even the slightest hint of disease. (Hence the mention of Thelusian Flu earlier.) Once the antibodies are activated, they decide that "regular" humans are essentially viral, and must be destroyed. There is potentially a tragic arc to science creating lethal beauty, but Kingsley is tedious and one-note, and the children themselves are vaguely beatific blank slates. As episodes go, this had a clever enough conclusion—using the transporter to restore the afflicted was satisfying, and it's always fun to see Picard save the day. The problem is, "Selection" depends on Pulaski for emotional depth, and that gets old, fast.

Grade: C+

"Matter Of Honor"

Oh thank god yes.

So far I haven't had a whole lot of surprises doing these recaps. I knew the first season was largely terrible, I knew I didn't much care for Tasha Yar or Dr. Pulaski, I knew Patrick Stewart kicked ass, and all of these beliefs have been confirmed. There are little surprises, though, and the best of them is that I really dig William T. Riker. Jonathan Frakes has always struck me as a nice enough guy, but I don't remember having an opinion on him when I first watched the series. Data and Picard took up most of my attention. As I got older, somewhere I got the idea that Riker wasn't all that highly respected among Trek fans. I decided he was smarmy, and dumb, and, at best, a place-filler for the real leads to bounce lines off.

Screw that. Riker is really, really fun. He is a bit smarmy, but the guy is so clearly having fun with his job that it's infectious. He's the Han Solo of the group, and while Frakes doesn't quite have Harrison Ford's charisma (Frakes is too familiar to be really rakish; he's like an uncle who occasionally sells you pot), he does well as a guy who loves his work, loves his friends, and every once in a while likes to screw around with both. For fun, check out the way he stands. It's easy to mimic, easy to mock, but it's also bad-ass, because he knows he's a little ridiculous and he doesn't care. Kind of makes me think of Timothy Olyphant's strut, although that is a deliberate, "I'm walking this way to keep myself from murdering someone each time I put my foot down," whereas with Riker, it's like he just wants to make sure you know he's screwing with you. He takes his duties seriously, but he also finds a lot of things pretty hilarious at the same time, and I dig that.

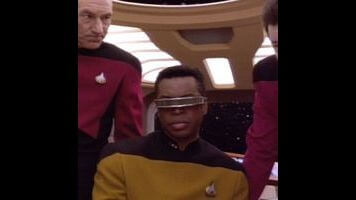

Another surprise is how much I like Worf. He hasn't gotten as much to do yet, but the show is getting better at giving him lines, and letting him be funny. (The eye-roll he does when Pulaski demands the children be saved in "Selection" is great.) Worf and Riker's relationship is probably the closest the show gets to really capturing that TOS tone: the two are friends, but there's an edgy playfulness to that friendship that you don't really see in, say, Data and Geordi's interactions. Worf doesn't do a lot in "Matter of Honor," but what he does get is choice, and he's basically an entry-point to Klingon culture as a whole. We've seen how Worf deals with others of his race in the context of the Enterprise, but what happens when a mere human is set adrift in Klingon culture, without the recourse of the Federation to aid them?

"Honor" has Riker signing on for a temporary re-assignment to the Klingon ship Pagh. It's part of an officer exchange program, but no one from Starfleet has ever attempt to serve with Klingons. The impression we get here is that it's a potentially dangerous mission, but not an inherently suicidal one. Picard first introduces Riker to the idea while the two of them are playing some sort of target practice with lasers game, and the captain clearly wants Riker to volunteer. Picard is not one to risk his crew lightly. (Which we'll have even better proof of next episode.) He does, though, take the Enterprise's mission of exploration and discovery very seriously, and what's really cool here is that Picard is encouraging Riker to take the assignment for philosophical reasons. It's a plot motivated by one character's eagerness to learn something knew.

Plus, Riker clearly gets a kick out of doing his job well. He takes to this new assignment with what can only be deemed as "gusto," sampling ugly Klingon delicacies, and questioning Worf as to the subtleties of Klingon high command. (Turns out it's the job of the first officer to assassinate his captain the moment the captain proves unworthy to lead. Any bets on how a battle royale between Riker and Picard would turn out?) One of the impressive things about "Honor" is how it manages to set up its premise, and deliver sufficiently on that premise, in the space of a single episode. It's easy to imagine this playing out over multiple hours, and if it happened in a modern genre show, that's probably how it would go—Riker taking some courses, then slowly working his way into Klingon society, developing relationships, questioning his own identity as he starts to relate more and more to their warlike ways, until finally he's forced to make some kind of dramatic choice, betraying a part of himself in the name of survival.

That could've been compelling, but I doubt TNG could pull it off as the show currently is, and there's also a great deal to be said for brevity. As a single unit, "Honor" is forced to refine its major conflicts down to their most basic elements. So we get a scene with Riker eating Klingon food, to set us up for a later scene on the Pagh where he has to prove himself to his shipmates by munching on some live worms. We get a danger, with the biological organism that threatens the integrity of the Pagh's hull, putting the ship at risk and giving the already suspicious Captain Kargan ample reason to mistrust Riker and the Enterprise. There's an arc here, and while I'm not sure I'd go so far as to say Riker goes through significant change, there's a sense of him coming into his own. Riker stands equal (or better) with the Klingons, and it works because the Klingons aren't softened or diminished in order to make them "safer." TNG is still painting with broad strokes, but its respect for the alien culture here makes for some of the best dramatic moments I've seen on the show. Riker taking over the Pagh by tricking Kargan is a cheer-worthy twist, and it wouldn't have worked if it didn't feel earned.

There are some minor quibbles. I don't mind the sub-plot with Mendon learning valuable lessons in the art of communication, but combined with Riker's domination on the Pagh, it skews a little too close to the "humanity is the greatest!" tone the series leans on. Some of Kargan's behavior is on the inexplicable side, especially considering his paranoia. He can't possibly believe that Riker would willingly help destroy the Enterprise, and while I can see him trying to test the first officer by drawing out his loyalties, Riker probably should've been thrown in the brig once Kargan decided that Starfleet wanted the Pagh destroyed. Also, why the hell are the lights so dim on the Pagh, anyway? Are Klingons just that into the color red? Maybe it's a genetic thing, in which case Worf should spend most of his time on the Enterprise bridge squinting.

This was really excellent, though, and between it and "Measure of a Man," I finally feel like TNG is starting to pay off on investments. Much of what Riker does here follows the familiar genre pattern of an outsider making a place for himself in a new society, but instead of making the story overly-predictable, that familiarity resonates. It's deeply satisfying, which is not a feeling I often get watching this series. I hope it lasts.

Grade: A-

"The Measure Of A Man"

It must be a rule every starship captain's adventures must at some point put him in contact with old flames. How else can you explain the presence in "Measure of a Man" of Phillipa Louvois, former lover and adversary to Jean-Luc Picard, and current JAG Captain at Starbase 173? Much like the "Court Martial" episode of TOS, "Measure" tries to mine some emotion out of a years buried relationship, and while watching the two characters spar is amusing, it's not really necessary. (It also doesn't help that Amanda McBroom isn't anywhere near the same acting league as Stewart.) Picard and Phillipa are not the heart of this story. Data is. And for once, we finally get an episode that lives up to his character's potential.

As viewers, there are certain things we tend to accept without asking when we watch sci-fi and fantasy. Those elements change from show to show, but the basic principle stays the same: we accept what is presented as truth in the universe we're watching. We don't have warp travel, we don't have spaceships like the Enterprise, we don't have instant teleportation or replicators or holodecks, but all of these are presented as given on TNG, and so we don't question there presence. Sure, we can wonder as to the plausibility of certain elements, but unless a show starts breaking its internal rules, we're willing to take quite a lot at face value. Just the name alone, "science fiction," has our expectations prepared. We don't need to see the physics explained in detail as to how Picard and his crew sail the stars. Just to know there's a ship is enough.

For a while now, Data has been one of those accepted truths. Anyone who's spent much time at the movies has seen robots before, so he's not really an anomaly to us. There's Geordi's visor, and Worf, so we already know that this new universe is not solely populated by understandable technology or recognizable humanoids. Yet all along, there have been these certain threads of disquiet as to just what his position in Starfleet, and among his fellow crewmembers, really is. There's a reason that "fully functional" line is so creepy, after all. It's bad writing, but it's also a reminder of Data's uniqueness, his distinction and separation from basic humanity interaction. It's not like anybody had sex with the toaster, but at the same time, just how much of Data is programmed response? How much is choice?

Actually, I doubt that's a question that has plagued me much, since there's never really been any doubt that Data has a soul, that he's a fully conscious, self-realized entity. So maybe the real question, then, is how the other characters view him. Even if we as audience members are conditioned to accept certain central tenets, Picard an the others are not. They accept the holodeck because it's been there for ages, same with warp speed, but Data is a new idea, and even if we have no trouble believing in his basic reality and rights within the series' context, there's no rule that says the characters that live in that context have to agree with us. Imagine if cars started demanding equal pay, or if refrigerators would only be willing to hold certain kinds of food.

On the one hand, it makes sense that a scientist would want to take Data apart to see how he works. It's a bad idea to us, and to the people on the Enterprise, because we "know" Data, and his presence on the show (and on the ship) is as valuable as anyone else's. (In some cases, quite a bit more.) To Starfleet, though, Data is simply another computational tool. So now we get to spend some time trying to find out how our acceptance of the idea of Data, and Picard and the others' belief in him, can be expressed in concrete enough terms to defend Data's rights.

It's surprising that Pulaski isn't more present in "Man," considering her general feelings towards the android. I'm not sure if this was a conscious choice, or simply a matter of time; she appears at Data's farewell party, and doesn't have any snide comments to make, so that's all right. She doesn't even rise to some very obvious bait in the poker game at the start of the episode. (Ahhh, TNG poker. This, I remember.) Picard does most of the heavy lifting here, as Data's ability to come to his own defense is one of the questions that needs to be answered. Riker gets a few meaty scenes, and Geordi has a semi-tearful goodbye to Data, but mostly, this one is all the captain. He's the one trading barbs with Phillipa, he's the one who demands a hearing be called to defend Data's rights, and it's his efforts that ultimately save Data from dismantling. Spiner and Stewart work well together, as Data's trusting nature and straight-forwardness meshes nicely with Picard's clear contempt for the complexities of social convention. It's great to see Picard stepping in to protect his crew, and his clear emotional investment in the issue (an issue he himself may have had some questions on before) makes his final arguments in the hearing powerful and moving.

As for the episode's flaws, well, having Guinan basically spell out "THIS IS LIKE SLAVERY" was unnecessary. While I appreciated the overall discussion, I sometimes wondered if the arguments made against Data's autonomy were a little soft. (As when Maddox, the scientist determined the see what makes Data tick, says that no one would allow a ship's computer to refuse a refit. I think if the computer was actually capable of making the refusal, the situation would change. Isn't Data's desire for survival here proof enough of consciousness?) I really, really didn't like shoehorning Riker into leading the prosecution's case, because it's a very obvious attempt to create fake drama. Still, he does well with the role. There's a great scene which shows Riker studying Data's specs; he finds information that can help him "win," grins, and then realizes that in winning, he'd be dooming a friend.

Overall, this was as good as "Matter of Honor," albeit in a different way. "Honor" was an adventure story; "Measure" is the sort of profound philosophizing that Trek has always made its bread and butter. Soft arguments or no, "Measure" does well to not play anyone as the bad guy. Even Maddox, a definite irritant, is proven to be more blinded by his passion for his work (and a fear of his own inadequacies) than a villain. Hearing him call Data "he" instead of "it" at the end was nice. (Less nice: Phillipa immediately pointing out the change. Apparently, we can be trusted to follow high-minded debate, but as an audience we suffer from serious pronoun trouble.) TNG hasn't lost its flaws, but it's finally, definitively shown that it can be great. The next time I find myself wishing I could fast-forward to the good parts, I'll just remember Picard's big speech here, or Riker taking down the Pagh's second-in-command. I don't mind waiting for more of that.

Grade: A-

Stray Observations:

- Hey, Brian Thompson! Between this and X-Files, I can't seem to shake him lately.

- Is "Unnatural Selection" the first episode to give Chief O'Brien a name? It's good to see him popping up on the show more regularly and getting lines. They even included him in the poker game.

- I mentioned "Naked Now" earlier; "Measure" references Tasha and Data's physical intimacy, and does so to far great emotional and dramatic impact than the actual original scene did. And Picard's time on the Stargazer is also mentioned, which means that two of my least favorite episodes now have some small reason to exist.

- Next week, it's "The Dauphin," "Contagion," and "The Royale."