Star Trek: "The Paradise Syndrome"/"And The Children Shall Lead"

Indians are just so adorable, aren't they? I mean Native Americans, but that's such a cold, clinical name. "Indians" was good enough for our forefathers, and "Indians" they shall remain in our hearts. Such sweet, childish innocents! I bet the only language they speak (aside from broken English) is friendship, their only currency, hugs. We could learn a lot from them, about nature and one-ness and living in triangles. We feel terrible about the whole mass murder thing, but to compensate, we will idealize them in a fashion that in no way allows them the full culpability, intelligence, and complexity of an actual human being. No, you don't have to say "Thank you" in whatever jutted syllable baby gibberish you call words. We already know what you mean. And you're already welcome.

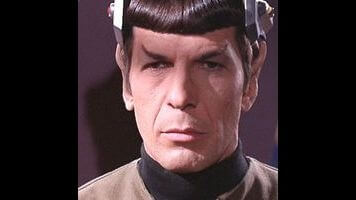

If this sounds bitter, I just watched "The Paradise Syndrome," and have been assured on multiple fronts that it works as an example of how the rest of the third season will play out. This is not happy knowledge. "Syndrome" isn't as dire as "Spock's Brain," but it is terribly silly and not very well-thought out. Apart from the occasional clunker, the first couple seasons of Trek are solid TV; the cultural image of the series is usually goofy aliens and Shatner chewing the same three sets over and over again, and going by seasons one and two, that image is, if not entirely unearned, more than a little exaggerated. Only four episodes into this season, though, and I'm realizing where the stereotype comes from. "Syndrome" features two of Trek's most familiar liabilities, a ridiculous plot and a ridiculous leading man. And unfortunately, it provides no substance to distract from either.

An un-named, Earth-like planet is threatened by an approaching asteroid. Before stopping the asteroid, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy beam down to the planet's surface for a quick walk-around. Already this doesn't make a whole lot of sense. If the planet is in danger, if the Enterprise has plans to divert the threat, and if those plans require meeting the asteroid at a very specific time and position (as Spock later explains to McCoy), why visit the planet beforehand? Their records already indicate that the local population is pre-space travel, and there's no intention or need to evacuate them. The only reason to show up while the threat is active is to allow what happens next to happen: a crewmember (Kirk, natch) is left behind. (There's also the question of why the Federation is involving themselves in this sort of activity at all, as it seems perilously close to violating the Prime Directive as well as incredibly time consuming, but I'll let that pass. Because really, in an idealized sort of way, having star-ships running around protecting those who can't, apparently, protect themselves is rather sweet.)

While wandering around the area—which, it must be said, is lovely and unusual for the series, in that it's an outdoor, forest setting that isn't faked—our heroes find an obelisk covered in unfamiliar writing. The indigenous (or seemingly indigenous) population doesn't have the technology to build such a thing, which is strange; even stranger is that when Kirk stands on the obelisk's base and calls up to the Enterprise, the stone under his feet slides away, dropping him into the statue's based to land on a control panel in an enclosure below. The panel zaps him, knocking him unconscious. Spock and McCoy search the area for a few hours, but are unable to find him; given that time is running out on their saving-the-world mission, they're forced to temporarily abandon the captain.

McCoy's never been the cuddliest of characters, but he spends most of "Syndrome" arguing loudly with whomever happens to be standing closest, and unsurprisingly, that "whom" is almost always Spock. Their relationship is one of the series' most compellingly rough-edged, with McCoy's knee-jerk emotionalism constantly running aground of Spock's pragmatism, but while other episodes have managed the balance between the two, here McCoy falls into a pattern of unthinking opposition. The dynamic remains effective—Spock's choices make the situation consistently worse, despite the fact that they're always the right choices, which puts McCoy in the weird position of being proven right despite having his reasoning be essentially flawed. But more than once, the doctor's nay-saying makes him appear unforgivably dense, like when Spock has to actually give him a careful, step-by-step demonstration of Enterprise's Armageddon-style objective.

But at least the scenes with the George and Martha the sci-fi set are buoyed by a clear objective. Kirk's sojourn with the Indians (who here are about as non-Native American as you can get without being actual from-India Indians) is a campy, inane side-trip that features Shatner at his all around most ridiculous, full of flat, ineffectual characters, with a story that's supposed to be moving but is really just pathetic. When Kirk wakes up from the mind-zapping, his memory is gone. He's soon discovered by two women from the nearby tribe of generically peaceful folks (Spock, from a distance, identifies them as a mixture of "Navajo, Mohican, and Delaware Indians"). They take him back to their home on the assumption that he's a god because, hey, white man, obelisk, you do the math. The men of the tribe, most notably Salish, the "medicine chief," are suspicious, but Kirk proves his worth when he brings a drowned boy back to life through a complex system of CPR and low-impact aerobics. The big Chief, in fact, is so convinced that he fires Salish on the spot and gives Kirk Salish's job. Oh, and Kirk can't really remember his name, and calls himself Kirok instead.

Kirok's adventures in Frontier Land follow a predictable path—he even gets married to the tribal priestess, Miramanee, thus making an enemy out of Salish for life. At the start of episode, Kirk's immediate infatuation with the landscape leads McCoy to say he's suffering from "Tahiti Syndrome," essentially so over-stressed and over-worked that he's pining for a simpler, more idyllic life. Which he then gets in the form of some Saturday morning kid show costumes and giggly girl wrestling. It would all be easier to take if it wasn't for the connection to actual Native Americans. We eventually learn that the people Kirk meets are the descendants of tribes transplanted from our own Earth by an alien race known as the "Preservers." (McCoy theorizes that this is why there are so many humanoid races spread around the universe.) So all the trite ritual, the fact that the populace hasn't evolved in any way in the hundreds of years they've been on their own, it's supposed to mean that they live in paradise, but what it really comes off as is Noble Savage style silliness. This might have been progressive when the episode first aired, but I can't help thinking the episode would've fared better if the aliens actually had been aliens. Nothing would've saved the look on Kirk's face when he thinks "I have found paradise," though.

But we still haven't explained that obelisk, have we. After the Enterprise fails to shift the asteroid, Spock falls to obsessing over the strange language printed on the statue's side. It's a "Vulcan hunch," and it pays off. The obelisk was left by the Preservers for the Indians to use in case of an asteroid threat. Whenever the sky darkens, the medicine chief is supposed to follow the ancient ritual and the obelisk with take care of the problem. (Apparently, this happens a lot.) Too bad Salish's father died without passing on the information. Now the assumption in the tribe is that Kirok's assumed godhood will keep them safe. When he turns out to be just as much in the dark as everybody else, the situation turns ugly, and it's only Spock and McCoy's well-timed arrival that keeps Kirk from being stoned to death. (Or is it? I couldn't tell if the "peaceful" Indians were frightened off by the men appearing out of nowhere, or if they just decided they'd thrown enough rocks.)

It's too late for Miramanee, though. Medical science can't top plot contrivance, so Mrs. Kirok dies, taking Kirk's unborn child along with her. Kirk and Spock manage to get the obelisk working properly, as the language on the statue's side is a series of notes, which, ha-ha, just happen to match up with tones Kirk makes when he says, "Kirk to Enterprise." The day is saved, Kirk gets his memory back after a quick mind-meld, and while I think we're supposed to experience some kind of grief in the final shot of Kirk comforting his dying wife, that's undercut by the wife's lack of visible injuries and decision to lie on her back with one leg slightly raised like a pin-up model. All in all, this was goofy without being anywhere close to good.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.