Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace marked a beginning for more than Star Wars

George Lucas let it all hang out in the first Star Wars prequel, influencing a generation of blockbusters

In 1999, when Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace was first released in theaters, it had been 22 years since the release of just plain old Star Wars in 1977. Now, in 2024, the number of extant Star Wars features has more than doubled, and it’s only been five years since the last one was in theaters (compared to the 16 that elapsed between Return Of The Jedi and Phantom Menace). But it’s also been a full quarter-century since Phantom Menace revived, saved, remodeled, and/or killed Star Wars, depending on who you ask, when you ask them, and how old they are, among other factors. That passage of time is at once unremarkable—1999, one of the best movie years ever, has a whole list of movies that are now 25 years old in a way that will seem impossible to those who were adults at the time, and shrugworthy to those who weren’t—and deeply resonant. Not only is the first prequel less of a hot-button topic as it once was, it’s finally part of the cinema firmament after feeling quite apart from it for many years.

For example: As recently as 2015, in the run-up to the release of the sequel-trilogy reviver The Force Awakens, essays defending the prequels were still capable of sending internet commenters into paroxysms of fury. This kind of passion helped create the illusion that any number of offshoots—whether the acclaimed cartoon spinoff The Clone Wars or the old-internet prequel-dissection videos featuring some decorative rape jokes—were more beloved than the prequels themselves. Prequel defenders have received their own ironic comeuppance in the years since, now that at least some of the turnaround on the only Star Wars trilogy directed entirely by George Lucas has been predicated on similar disgust (at least in some corners) over the allegedly corporate-noted-to-death sequel trilogy. Anyone who happened to love both Attack Of The Clones and The Last Jedi (hello there) was forced to see one used as a cudgel against the other, a stunning spectacle of reactionary hypocrisy and omnidirectional shortsightedness. Have the TV shows “redeemed” the sequels yet, either by visibly costing much less money or by adding some more nuanced details into the story of how galactic history came to repeat itself? I’m not sure. It seems bound to happen at some point, and it sounds exhausting.

So while it’s still worth talking about The Phantom Menace on its silver anniversary, maybe it’s best to try to look at the film apart from the treadmill of Star Wars discourse, and consider it as a discrete art object. This is surprisingly easy to do, for two reasons, one stated more often than the other. First, Phantom Menace is the prequel that feels most like unfiltered, unfettered, pure-cut George Lucas, for better and worse. Second, it’s the prequel that feels the most influential on other movies of the past 25 years.

It’s easy enough to make the case for both Attack Of The Clones and Revenge Of The Sith as “better” movies than The Phantom Menace (though Clones seems to have taken over as the consensus choice for worst of the prequels). Attack Of The Clones is an action-packed, lightsaber-heavy romp that gives Obi-Wan Kenobi the stronger role that many expected from Phantom Menace, taking fuller advantage of both Ewan McGregor’s individual charisma and his ability to playfully imitate Alec Guinness intonations. Revenge Of The Sith hurtles forward with operatic momentum, swashbuckling its way straight into a democracy-killing hell. Phantom Menace, however, finds George Lucas unencumbered with whatever responsibilities he assumed in order to keep the sequel-trilogy story moving along. Among his fellow movie brats of the 1970s, it’s nearly at Brian De Palma levels of expressing pure imaginative whims, with the even weirder distinction of somehow being packaged as the entry point in a mega-popular, child-friendly fantasy-adventure series. The other prequels couldn’t help but be informed by unpredictable outside factors, whether negatively (Lucas’s awareness of Phantom Menace’s fan reception in certain circles) or provocatively (the run-up to the second Iraq War that informs the politics of Revenge Of The Sith). The Phantom Menace is probably the closest we’ll ever get to how Lucas truly envisioned Star Wars in the latter half of his life.

At the same time, it’s not pure rehash. While much of Phantom Menace is told through Lucas’ established Star Wars language, both visual and verbal—the wipes, the cockpit shots, “I have a bad feeling about this”—there are also times where he tinkers with it just enough to throw the audience off. Yes, there’s the routine “bad feeling” airing early on, but the real dialogue motif of Phantom Menace is a series of variations on “you assume too much,” a perfect kickoff refrain for a series that’s partially about the Jedi failing to fully comprehend or investigate the danger in their midst (not to mention a handy reminder for a hotly anticipated movie that plenty of viewers had been picturing in their heads for years). One of the movie’s best and most jarring visual departures sees Lucas cut to a point-of-view shot, exceedingly rare for the series, putting the audience in C-3PO’s shoes while he watches helplessly as Anakin cheerfully packs his meager belongings and matter-of-factly abandons his unfinished creation. Little Jake Lloyd’s nonchalant “You’ve been a great pal. I’ll make sure mom doesn’t sell you or anything,” is one of the funniest line-readings of the movie. (And how’s this for some poetry-like rhyming: The only other clear character-POV shot I can recall from the prequels comes in Revenge Of The Sith, where now the vantage is Anakin himself—as he completes his transformation into machine-man, leaving his old human self behind.)

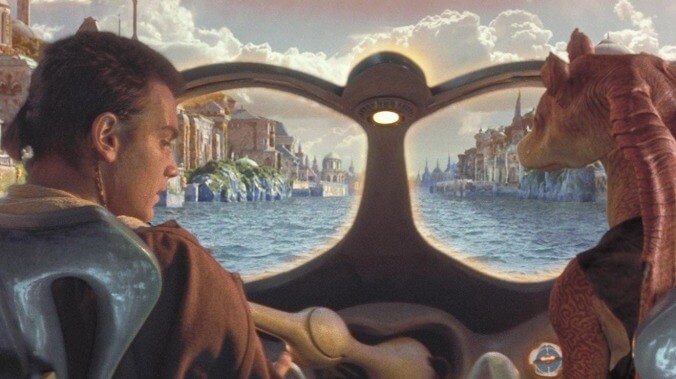

Even some of the movie’s most widely reviled elements feel like Lucas on a mission, half borne of deep conviction and half whimsically exploratory. That Phantom Menace begins by sending its leading Jedi knights into a tedious (if ultimately consequential) trade dispute feels like a dual statement of purpose: You are about to see the kind of annoying bullshit the Jedi are expected to deal with on the regular; all the better for Lucas to distract himself with the underwater Gungan city and a subsequent fantastic voyage through the planet core of Naboo. Later, Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) doesn’t just make a bet with Tatooine resident Watto; he makes a series of bets and parlays drawing the creature deeper into his gambling addiction. In The Phantom Menace, Lucas seems fixated not just on offering new planets, but worlds within worlds, right down to the controversial midi-chlorians that form the living force. Beyond its thematic unity, this rococo world-building makes The Phantom Menace an eyeball-quenching pleasure for anyone willing to actually look at it, rather than listen for the (abundant) moments of clunky dialogue or underdirected acting.

Perhaps more surprising, though it probably shouldn’t be: Plenty of other gifted filmmakers were among those paying devoted attention. Lucas’ influence goes beyond the most obvious technical aspects of Phantom Menace’s role in the digital-cinema transition of the early 21st century. Yes, Jar Jar Binks was a major human-digital hybrid performance long before anyone advocated for an Andy Serkis Oscar nomination; yes, the sheer volume of digital effects used for characters, sets, props, and general mise-en-scène is revolutionary (even if it wasn’t until Attack Of The Clones that Lucas actually shot on digital). Yes, prequels became far more prevalent in popular culture; sometimes, they’d even be good! But there’s a Phantom Menace aesthetic that goes beyond “use a lot of computers,” and it’s become its own movie-saving lifeforce in the years since.

Around the movie’s 10th anniversary, for example, the theatrical experience got a new standard-bearer with the release of Avatar. Of course, Avatar reflects the interests and sensibilities of James Cameron: roughnecks trading cornball tough-guy quips, cutting-edge visual effects, wonder and terror in the face of nature, an all-the-stops climax. But pre-Avatar, had Cameron ever made a movie with such a menagerie of creatures, and such a cheerful willingness to simply spend time noodling through a bizarre world of his own creation? If Avatar and its sequel now feel like quintessential Cameron, it seems like this was unlocked by the freedom of Lucas’ movie. It’s as if the whole thing emerged from Naboo’s planet core, where there’s always a bigger fish.

But the biggest year of Phantom Menace’s long afterlife has to be 2018, just shy of the movie’s 20th anniversary, when its influence helped sustain two very different comic-book franchises. Black Panther remains the pinnacle of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, boosted by its sincere, complex emotions and the clear sensibility of its then-whiz-kid director, Ryan Coogler. It’s also clear that Coogler must have watched Phantom Menace a bunch as a kid, especially as Black Panther’s climax unfolds. The confrontation between Black Panther and Killmonger mimics the pacing-tiger energy of the Darth Maul lightsaber battle from Phantom Menace, right down to their separation by a futuristic force field. It doesn’t seem coincidental that Coogler cross-cuts this action with a large-scale battle in a verdant field featuring large-scale shields (like the Gungan ground war) and a side adventure where one character unexpectedly pilots a ship on an aerial mission (like Anakin’s space battle, with Martin Freeman hilariously cast in the prepubescent-boy role). Now this, as they say, is podracing.

Later in 2018, the DCEU (RIP) had its biggest global smash with Aquaman, which brought a Lucas-esque muchness to its colorful underwater world that often plays more like space fantasy than superhero narrative. When director James Wan cuts to Topo, the drum-playing octopus; dresses Mera in an elaborate jellyfish gown; sends Aquaman to uncharted seas at the center of the Earth (in other words, the planet core!); and marshals all manner of undersea creatures including a fellow called the Brine King for a big-finale undersea battle, he’s indulging an extravagantly silly style that might not be possible without The Phantom Menace. Even if some of these characters and concepts come from the comics, their adaptations can be downright timid on a visual level; Black Panther and Aquaman show that it doesn’t have to be this way.

Just to start, that’s three billion-dollar movies that take at least some visual or structural cues from Phantom Menace to make the world of global blockbusters a little less boring. That particular category of mega-movie might be even more invigorated if Lucas still saw fit to make movies, whether more mainstream fare or the experiments he’s always threatened to fritter away his fortune making (and we can only hope have been in secret production in the nearly 20 years since Revenge Of The Sith marked his most recent directorial effort). Yet as more and more time passes between Phantom Menace hype and the stranger, more idiosyncratic reality of the movie, it seems more plausible that with the first prequel, Lucas was accidentally doing both at once: Making an influential mainstream smash with the careless freedom of a backyard experiment. The series could, did, and will start semi-fresh again, but Phantom Menace is the Star Wars movie that keeps on beginning.